Timeline: Race, Gender, Class, Sex

Created by Dino Franco Felluga on Tue, 08/24/2021 - 13:16

Part of Group:

This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research a topic that teaches us something about race, class, gender, or sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class, gender, or sex to our collective resources in COVE Editions. Provide images, sources and sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural element that you are presenting. Interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research a topic that teaches us something about race, class, gender, or sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class, gender, or sex to our collective resources in COVE Editions. Provide images, sources and sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural element that you are presenting. Interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

Timeline

Chronological table

|

Date |

Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 to 1997 |

Milestone Comics is Founded‘‘If you’re not there, you just won’t get it.’’ ‘We got together to fill what we saw as a lack of minority representation in comics," Denys Cowan. In 1993, independent publishing company, Milestone Media is created by the four founding members: Derek T. Dingle, Dwayne McDuffie, Denys Cowan, and Michael Davis. Brown quotes McDuffie on what the main goal of the company is, "to increase the diversity of the comics industry by reflecting the complexity and the diversity of the real world that we all live in. We could have done just African American comics because that is obviously the experience that we understand best, but we realize that that is only one of many possible viewpoints that we want to bring forward for our readers (29)." The company ended in 1997. Brown, Jeffrey A. Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans Milestone Comics and Their Fans. University Press of Mississippi, 2000. |

Charlie Billings | ||

| 30 Jun 1977 to 30 Jun 1977 |

San Francisco Bisexual Center's First Press ConferenceOn June 30th of 1977, the San Francisco Bisexual Center has had it's first press conference. The speakers of the conference included one of the co-founders Dr. Harriet Leve, and others including Dr. Benjamin Spock, Dr. Phyllis Lyon, Ruth Falk, and Dr. Claude Steiner. These people have spoken up against the anti-gay activist and singer Anita Bryant, as she desired for homosexuals to never be allowed to become school teachers, which is what the speakers are fighting for. They have also discussed other civil rights issues as well, but it was Dr. Harriet Leve's goal to get across the fact that "It is imperative for bisexuals to support and form a unity with our gay sisters and brothers in order to demand what's rightfully ours" (Rubenstein 228). This powerful sentiment has perfectly demonstrated what the center is all about, which is the inclusion of every sexual identity and that they all deserve peace and freedom. The conference has been broadcasted on two local news TV programs and was reported and talked about by several radio stations all around San Francisco. It has also been included in many newspaper articles, such as The San Francisco Examiner, The Oakland Tribune, and The Bay Area Reporter, all very prominent sources of news during this time. Because of the popularity the conference has created, the Bisexual Center has seen a large increase in it population. Four Hundred and Thirty Five people have joined the center in just a month after the conference has taken place. The San Francisco Bisexual Center was on it's way to prominence. Sources Rubenstein, Maggi. “A Profile of the San Francisco Bisexual Center.” Journal of Homosexuality, 18 Oct. 2010, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J082v11n01_13. Gindorf, R., and EJ. Haeberle. “SAN FRANCISCO'S BISEXUAL CENTER AND THE EMERGENCE OF A BISEXUAL MOVEMENT.” BAY AREA BISEXUAL+ & PANSEXUAL NETWORK, 1998, https://www.babpn.org/sfbc.html. |

Braden Chandler | ||

| 23 Jun 1972 |

Title IX EnactmentOn June 23rd in 1972, Richard Nixon signed Title IX of the Education Amendments into law. Title IX was set into place to avoid discrimination based on sex, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance”. Since Title IX has gone into enactment, there has been a turning point in equality including education equality. Prior to the enactment, women only had limited access to programs and were often excluded which began the fight for women’s equality. At first, legislators were planning on adding this movement to the Civil Rights Act, Title VII, which “prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin”. Although Title IX relates to Title VII, it became its own legislation because of the power it holds. Title IX was still not practiced directly after the legislation was passed. It took time for people to adjust, one case involves United States vs. Virginia. The court case was argued January 17th, 1996 and wasn’t decided till June 26th, 1996; twenty years after title IX was already passed. This court case involved Virginia Military Institute a single-sex school that prepared men into citizen-soldiers. The case was taken to court due to violating Title IX by not opening the program towards women. In response to labeling the situation unconstitutional, VMI proposed an “identical” program: Virginia Women’s Institute for leadership. The court allowed them to open but once the educational programs were compared, they were not the equal. Women were still not getting the same education that men were receiving. In a 7-1 supreme court decision, it was concluded that Virginia’s male-only admission was deemed unconstitutional because there were not equal opportunities for women compared to the programs designed for men. A case that was positive towards the impact of Title IX includes Kelley vs. The Board of Trustees. On May 7th, 1993, the University of Illinois announced they had to cute four varsity sports from the athletics department. One of these sports included men’s swimming. In distress, the men on the swim team went to the board of trustees at the University and brought up a lawsuit against them. The school mentioned there needed to be budget cuts while still staying in line with Title IX. By the University complying with Title IX, it showed that education systems were following laws that were produced for equal rights among women. The school had to have an equal amount of men’s sports and women’s sports offered in order to comply with Title IX. This court case was very impactful towards the women’s movement and improved the effects of Title IX. United States Department of Justice. “Equal Access to Education: Forty Years of Title IX.” Last modified June 23, 2012. http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/edu/documents/titleixreport.pdf. United States v. Ratliff - Casemine.com. https://www.casemine.com/judgement/us/5914ee78add7b0493495f332. “United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996).” Justia Law, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/518/515/. “Title IX Enacted.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 16 Nov. 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/title-ix-enacted. |

Madelyn Menke | ||

| 1972 to 1986 |

Luke CageAt this point in comics history, publishers were looking to other forms of media for inspiration, clearly taking inspiration from the Blaxploitation films of the era to emulate into comic book characters. Both of the two big comic publishers, DC and Marvel, tried and failed to create long-lasting black superheros. Brown claims the reason for this is that their black characters were too closely identified with the limited stereotype commonly found in the blaxploitation films of the era. In the introduction of Frances Gatewar and John Jennings' book The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art, they claim that comics traffic in stereotypes and fixity, often portraying black superheros in a positive light due to their physicality and nothing else. They claim that black characters have inherent issues built into the very conventions of the genre due to the fact that the Black Body has historically been linked to physicality and not intelligence. 20 years from now, Milestone Comics will set out to reverse this sterotype, creating characters that are centered around their compassion and intelligence rather than their physicality.

Brown, Jeffrey A. Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans Milestone Comics and Their Fans. University Press of Mississippi, 2000. Gateward, Frances K., and John Jennings. The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art. Rutgers University Press, 2015. |

Charlie Billings | ||

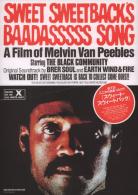

| 31 Mar 1971 |

1971: BlaxploitationThe term "blaxploitation" was coined by Junius Griffin, the then-head of the Los Angeles National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in the early 70s as a criticism for the less-than-positive images of African Americans depicted in the genre, and his influence would later contribute to its demise. In 1971, the film Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song was released. The film is often regarded as the best example of blaxploitation and credited as the first film of its kind. |

Kennedy Christian | ||

| circa. 1970 |

Black-Owned Communications Alliance PSA‘‘if the child is Black and can’t even imagine a hero the same color he or she is.’’ Brown claims that this advertisement's concern is clear, that children are impressionable and learn from what they see (3). At this point in time there were hardly any black superheros that children could identify with. Brown later says, "for comic book readers of different ethnic backgrounds there were no heroic models that they could directly identify with, no heroes they could call their own. Instead, they were required to imaginatively identify across boundaries of race since the only depiction of visible minorities in most comic books were the nameless criminals and barbarous savages that the real heroes defeated month after month (3)." This ad calls attention to the need for more diverse role models to reflect the diverse audience that is comic consumers. Brown, Jeffrey A. Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans Milestone Comics and Their Fans. University Press of Mississippi, 2000.

|

Charlie Billings | ||

| 1970 to 1983 |

The Dirty War: Timeline

June 8, 1970: Juan Carlos Ongania is forced to resign, paving the way for Juan Peron to return to office. October 12, 1973: Juan Peron takes office again, signalling a return to a pre-military rule government. June 1, 1974: Juan Peron dies, his wife, Isabel Peron, takes the office in his stead. March 24, 1976: Isabel Peron is arrested and the military announces The Act of National Reorganization, with which they intended to restore “"proper moral values"' national security, economic efficiency and "authentic representative democracy”, with June, 1977: The banks in Argentina were deregulated, allowing lenders to charge borrowers and reward depositors with whatever rates they desired. This was an attempt to stimulate the economy, however the ultimate result was middling, devaluing the Argentine peso by encouragin more people to spend their money. March 29, 1981: General Robierto Viola takes the presidency after Videla steps down. December 11, 1981: An internal coup removes Viola, placing General Leopoldo Galtieri in the Casa Rosada. Announced over a number of speeches that he would reign in the military so that it could once again resemble a cohesive force of order. April 2, 1982: Argentine forces make landfall on the contested Falklands Islands, which were caught between the claims of the Argentinean government and the British. The goal was to refocus the military which had been given a great deal of power during the junta, but nothing to do with it. However, none of the military leaders anticipated an actual war to break out. When it did, though, what followed was a mad dash by generals to attempt to form a cohesive defence of the islands. Something that had been made difficult by their decision to send new recruits to garrison it, with a commander that had never lead troops, into a terrain that none of them were familiar with. While it is believed that the Argentine defeat was not responsible for the ultimate fall of the Junta, it is widely accepted that it did accelerate it. December, 1983: The transition from military rule to a civilian is enacted marking the end of the junta. 1985: Two years after the civilian government was restored, Videla, amongst numerous other military official, had human rights abuse charges leveled against him. These charges ended in him receiving a life sentence which was carried out partially in a military prison, and partially in a civilian one.

|

Martin Repetto | ||

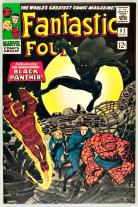

| Summer 1966 |

Black Panther First AppearanceAlthough superhero comics have been around since 1938 with the debut of Superman, it would be another 30 years before the debut of the first black superhero. In 1966, the superhero Black Panther made his debut in Marvel Comics' Fantastic Four #52 as a guest character. In 1969 Marvel debuted the 2nd ever black superhero, the Falcon, a sidekick to Captain America. The Falcon became a popular character but never surpassed the popularity of Captain America. Brown states, he was destined to remain in the shadow of Captain America; their often unequal relationship was seen by some as an unintended metaphor for the black experience in white America (20). Brown, Jeffrey A. Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans Milestone Comics and Their Fans. University Press of Mississippi, 2000. |

Charlie Billings | ||

| The end of the month Summer 1964 to The end of the month Summer 1964 |

July 21, 1964Black Nationalist speakers spoke to a large crowd. The crowd grew more emotional after each speech, and after one speech in particular a riot broke out, and the police charged the crowd as rioters threw bottles at them. The situation was calm again at 2am Wednesday, July 22. |

Sara Glacken | ||

| The end of the month Summer 1964 |

Investigations BeginThe President of the New York City Council, Paul Screvane announced that a Grand Jury would investigate the killing of James Powell. A United Nations demonstration was held in protest of terrorism against African Americans, and a riot followed this event. A march was planned for Monday by the Brooklyn CORE, and later they set up a rally where police eventually charged the mob without distincting innocent civilians and rioters, this continued until 7am on July 21. |

Sara Glacken | ||

| The middle of the month Summer 1964 to The middle of the month Summer 1964 |

Hostility ContinuesHostility between the community and the NYPD grew as rioters continued. A Black Citizens Council was held, and speakers tried reasoning with rioters for a peaceful protest, but members of the crowd disagreed. The crowd moved to Delaney Funeral Home, where a service was being held for Powell. One person threw a glass bottle at an officer, and he threw it back into the crowd. From this point on, bricks and bottles began to be thrown off rooftops into crowds. The ferocity ended at around 1:30am. By the end of the night, 45 stores were looted, 93 citizens and 27 police officers were injured, and 108 people were arrested. Source: |

Sara Glacken | ||

| The middle of the month Summer 1964 to The middle of the month Summer 1964 |

July 18, 1964James Powell’s funeral was held, and 250 people attended. The crowd called for the arrest of Gilligan as they were met with shards of glass and garbage lids thrown from residents of rooftops above them, and the swinging clubs of officers. The rioters looted over 22 stores, 19 people and 12 police officers were injured and 1 rioter died. |

Sara Glacken | ||

| The middle of the month Summer 1964 to The middle of the month Spring 1964 |

July 17, 1964The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) showed up at the scene the morning after his death. They were met by 50 NYPD officers carrying night sticks as they chanted, “Stop Killer Cops!” They called for discipline against the police for this act. |

Sara Glacken | ||

| The middle of the month Summer 1964 to The end of the month Summer 1964 |

The Harlem Riot of 1964July 16, 1964: James Powell was fatally shot by officer Thomas Giligan, sparking a six day long string of riots. Gilligan stated he heard glass break and inspected it to find Powell wielding a knife, and held this story through his trial where he was cleared of any crime. Witnesses claim they did not see Powell holding a knife, and people in the Harlem Community believed this was an act of police brutality.

July 17, 1964: The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) showed up at the scene the morning after his death. They were met by 50 NYPD officers carrying night sticks as they chanted, “Stop Killer Cops!” They called for discipline against the police for this act.

July 18, 1964: James Powell’s funeral was held, and 250 people attended. The crowd called for the arrest of Gilligan as they were met with shards of glass and garbage lids thrown from residents of rooftops above them, and the swinging clubs of officers. The rioters looted over 22 stores, 19 people and 12 police officers were injured and 1 rioter died.

July 19, 1964: Hostility between the community and the NYPD grew as rioters continued. A Black Citizens Council was held, and speakers tried reasoning with rioters for a peaceful protest, but members of the crowd disagreed. The crowd moved to Delaney Funeral Home, where a service was being held for Powell. One person threw a glass bottle at an officer, and he threw it back into the crowd. From this point on, bricks and bottles began to be thrown off rooftops into crowds. The ferocity ended at around 1:30am. By the end of the night, 45 stores were looted, 93 citizens and 27 police officers were injured, and 108 people were arrested.

July 20, 1964: The President of the New York City Council, Paul Screvane announced that a Grand Jury would investigate the killing of James Powell. A United Nations demonstration was held in protest of terrorism against African Americans, and a riot followed this event. A march was planned for Monday by the Brooklyn CORE, and later they set up a rally where police eventually charged the mob without distincting innocent civilians and rioters, this continued until 7am on July 21.

July 21, 1964: Black Nationalist speakers spoke to a large crowd. The crowd grew more emotional after each speech, and after one speech in particular a riot broke out, and the police charged the crowd as rioters threw bottles at them. The situation was calm again at 2am Wednesday, July 22. Sources: New York's 'Night Of Birmingham Horror' Sparked A Summer Of Riots : Code Switch : NPR Remembering James Powell and the Harlem Riots of 1964 | by darryl robertson | Medium |

Sara Glacken | ||

| The middle of the month Summer 1964 to The middle of the month Summer 1964 |

July 16, 1964James Powell was fatally shot by officer Thomas Giligan, sparking a six day long string of riots. Giligan stated he heard glass break and inspected it to find Powell wielding a knife, and held this story through his trial where he was cleared of any crime. Witnesses claim they did not see Powell holding a knife, and people in the Harlem Community believed this was an act of police brutality. |

Sara Glacken | ||

| 1963 |

The Feminine Mystique and the Second Wave of FeminismThe Second Wave of Feminism is after the ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920, which allowed women to vote. After this, feminism seemed to slow down greatly. During this time, there was the Great Depression and then World War Two took place. Women have always worked outside of home but never in the great numbers as during WW2 when the men were overseas. After the war, most women returned home, and let go of their jobs to the men. Over this time, there was activists fighting for women’s rights but the next greatly significant feminist movement is believed to have been started in the 1960s. This second wave of feminism broaden the debate of issues: sexuality, workplace, reproductive rights, and legal inequalities. This took place along with other social and political movements. Historians view the end of the second-wave feminist era in America to end in the early 1980s due to intra-feminism disputes over issues as pornography ad sexuality. Ten years after the publishing of "The Second Sex", “The Feminine Mystique" was published by American feminist writer Betty Friedan in 1963. She builds up the foundation of Simone de Beauvoir’s ideas and implemented the philosophical thought into her own personal experiences. Friedan was a writer, journalist and activist but she then got married and had children. She was a housewife in the suburbs for years and was unhappy and saw society’s pressure for women to be pink-collar workers, mothers and homemakers. Friedan wanted to see if she was alone in her feelings so she conducted interviews over 5 years to white middle-class women and they all felt the same dissatisfaction. These women felt trapped and unfulfilled in a world where men monopolized the positions of power and autonomy. In the book she criticized that the separation and constraint of motherhood and homemaking, were just to women. When in comparison to men, they were allowed to excel in power, politics and work while women were trapped. Friedan encouraged women to fight gender oppression, which she called “the problem that has no name”. Also, she wanted women to pursue careers that were “the life long commitment to an art or science, to politics or profession” (Friedan). Although there was a blind spot with “The Feminine Mystiques” with her not taking account systemic barriers especially towards working-class women and women of color where having a job isn’t a choice but a necessity. Although her book brought great attention to the disparities of the work force and the realization for women’s efforts to reform and realize the needed new rights at the workplace. This then helped make gains though civil rights and labor movements.

Works Cited Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, 286, 289. On women’s responses to the book, see Stephanie Coontz, A Strange Stirring: Th e Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s (New York: Basic Books, 2011 Turk, Katherine. “‘To Fulfill an Ambition of [Her] Own’: Work, Class, and Identity in The Feminine Mystique.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 36, no. 2, 2015, pp. 25–32. EBSCOhost, doi:10.5250/fronjwomestud.36.2.0025. |

Brooke Wisda | ||

| 1954 to 1970 |

Pan-Arabism: Nasser's PresidencyPan-Arabism came most alive during the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (جمال عبد الناصر حسين), typically referred to by Nasser, one of Egypt’s most notable leaders. He was president from 1954 until his death in 1970, and was highly influential to the development of Egypt and the Middle East. Almost immediately, Nasser began implementing elements of Pan-Arabism. This is very evident in one of his speeches given in 1954: “[A]ll countries that speak Arabic are our countries, and we must liberate our countries… the Muslims across the world are siblings, and siblings must cooperate in times of hardship… We the East, confronting the greed of the West, are one Nation!… [W]e desire— we the Arabs, we the Muslims, we the people of this East— to become one bloc.” (Nasser 1954) This idea was hammered into the Arab people over the next few years in a variety of different ways, and they began to get excited. Nasser was so influential that Syria became interested, so interested that they advocated for unity with Egypt, and for a time, there was talk of a combined state— the first step in creating the grand Pan-Arab state. However, even this union was short lived, and “turned into a struggle for dominion… the Egyptians ran Syria like a colony— and a badly run colony at that” (Kramer). So in 1961, the Syrians launched a coup that “ousted Nasser’s viceroy from Damascus and declared the union finished” (Kramer). And ever since this failed union of Egypt and Syria, Pan-Arabism has been withering, backsliding.

Works Cited Fallatah, Mohammed A. S. The Emergence Of Pan-arabism And Its Impact On Egyptian Foreign Policy: 1945-1981 (Egypt), University of Idaho, Ann Arbor, 1986. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/emergence-pan-arabism-impa.... Abou-El-Fadl, Reem. “Early Pan-Arabism in Egypt's July Revolution: The Free Officers' Political Formation and Policy-Making, 1946-54.” Nations and Nationalism, vol. 21, no. 2, 2015, pp. 289–308., https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12122. Accessed 12 Nov. 2021. Kramer, Martin. “Arab Nationalism: Mistaken Identity.” Arab Awakening and Islamic Revival, 2017, pp. 19–52., https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315082172-3. Accessed 12 Nov. 2021. |

Victoria Strong | ||

| 1948 |

Indian Government Outlaws Caste SystemThe Indian government outlawed discrimination on the basis of caste in 1948, after decades of movements and protests. This ratification became part of an amendment to the Indian constitution, with article 15 prohibiting discrimination based on caste and Article 17 declaring the practice of untouchability to be illegal. The anti-caste Dalit movement began with Jyotirao Phule in the mid-19th century, who worked to abolish the idea of “untouchability”. Figures such as B.R. Ambedkar and Gandhi also became prominent through advocacy for the abolishment of the caste system. Ambedkar campaigned for greater rights for Dalits in British India beginning in the 1920s and 30s, continuing even after independence in 1947, and during the national movement, Gandhi began using the term “Harijans” (God’s people) to refer to the untouchable class. He believed it to be a moral issue that could be abolished through goodwill among Hindus of the upper-caste. In 1935, the British Government of India came up with a list of 400 groups considered untouchable, including many native tribes, that would be afforded special privileges in order to combat historical discrimination. The groups included on this list became known as the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in the affirmative action plan established by the government. The Scheduled Castes are comprised of communities considered to be of the lowest in the social hierarchy, and the Scheduled Tribes include those communities who rejected the caste system in favor of living isolated from society in the jungles, forests, and mountains of India. These groups are eligible for preferential policies with reserved seats in legislatures, government jobs, public sector enterprises, and state-supervised educational institutions. Unfortunately, however, only a relatively small proportion of the lower castes have benefited from these preferential policies due to continued hostility and violence against the lower class in many parts of India even today. Image Source: “Jawaharlal Nehru Signing the Indian Constitution, in 1950.” Wikimedia Commons, 3 Aug. 2020, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jawaharlal_Nehru_signing_the_Ind.... Accessed 10 Nov. 2021. Works Cited:

Deshpande, Manali S. “History of the Indian Caste System and Its Impact on India Today.” California Polytechnic State University, 2010. Kositsky, Sasha Riser. “The Political Intensification of Caste: India Under the Raj .” Penn History Review , vol. 17, no. 1, Dec. 2009, https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=phr. Accessed 10 Nov. 2021. Mishra, Neha. “India and Colorism: The Finer Nuances .” Washington University Global Studies Law Review , vol. 14, no. 4, 2015, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1553&conte.... Accessed 10 Nov. 2021. Olcott, Mason. “The Caste System of India.” American Sociological Review, vol. 9, no. 6, Dec. 1944, pp. 648–657., https://www.jstor.org/stable/2085128?origin=crossref&seq=1#metadata_info.... Ramesh, Kamboju. “Caste System and Political Change in Indian Democracy – A Study.” International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts , vol. 8, no. 11, Nov. 2020, https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2011075.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov. 2021. |

Mahum Zaidi | ||

| 1947 |

Timeline of Black Representation in Comic BooksThe idea of creating a comic book featuring all African American characters was not a completley original idea in 1993 when Milestone Comics first debuted. In 1947, All Negro Comics, a privately produced comic made its debut. It was the first and only issue (Brown, 27). Brown, Jeffrey A. Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans Milestone Comics and Their Fans. University Press of Mississippi, 2000. |

Charlie Billings | ||

| Spring 1942 to The start of the month Autumn 1945 |

Japanese Internment Camps 1942December 7,1941 a day which will live in infamy. These words marked the attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States entry into the war. Fear brewed in the general American population as the war waged in the Pacific and in February 1942 Executive Order 9066 was passed to relocate 122,000 Japanese Americans on the west coast into internment camps to locations being: Topaz Internment Camp (Utah), Colorado River Internment Camp (Arizona), Gila River Internment Camp (Arizona), Granada Internment Camp (Colorado), Heart Mountain Internment Camp (Wyoming), Jerome Internment Camp (Arkansas), Manzanar Internment Camp (California), Minidoka Internment Camp (Idaho), Rohwer Internment Camp (Arkansas), Tule Lake Internment Camp (California). These camps were made as a means to increase surveillance against potential espionage. The WRA (War Relocation Association) hoped to have life in these camps normalized with their own form of governmental body with voting, jobs, and an inmate security force. Unfortunately, hindsight is always 20/20. Looking back, the actions we took out of fear of the Japanese became eerily close to what the Nazis did to the Jews. These people that were put into these camps were in many cases unable to pay for their mortgages and defaulted on their homes and properties during this time of confinement. When they were eventually released from these internment camps, they found themselves unable to go back to their old jobs. Even if they were to work in an internment camp, they would only be paid a fraction of the average American wage. They had to live in military style barracks and had to live off rationed food. Japanese internment camps were a clear example of discrimination based solely on race in American history. This blatant discrimination and harassment toward these people have largely been overlooked by the de facto reasoning that America were the glorious victors of World War 2, they were the ones that saved the world from imperial Japan and Nazi Germany. However, this is far from the truth. It is important to recognize that during times of war a nation and its people often turn to extremely racist and bigotry measures to secure their own safety. The relocation of Japanese Americans is eerily similar to the relocation of Native Americans, yet the former is often glanced passed in American education, while the latter has gained much notoriety and significance. Sources: Kessler, L. (1988). Fettered freedoms: The journalism of World War II japanese internment camps. Journalism History, 15(2-3), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/00947679.1988.12066665 National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Japanese-American internment during World War II. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation.

|

Stephen Jiang | ||

| 29 Sep 1911 to 6 Oct 1911 |

Clemence Housman imprisoned for tax resistance Laurence Housman escorts his sister Clemence Housman to Holloway Prison for her arrest, 29 September 2011. Wikimedia Commons. On Friday, September 29th, 1911, Clemence Housman was arrested for purposefully resisting the payment of taxes. This action was born out of her active participation and creative leadership within suffrage movements. Both Clemence and Laurence, who lived in Kensington, were geographically central to the suffrage movements, and loaned their creative skills to the Women’s Freedom League, through their efforts at their Suffrage Atelier. Clemence, with her considerable sewing skills, was the “chief banner-maker of the suffrage movement,” and collaborated with Laurence on the famous banner bearing the slogan “From Prison to Citizenship.” Clemence’s own tax resistance was part of a larger movement of the Women’s Tax Resistance League (WTRL), which used strategies of civil disobedience to campaign for women’s suffrage. Clemence, who lived with her brother, did not legally have any property on which to pay taxes, so she rented out a house in the rural community of Swanage, where she eluded the census of 2 April 1911. An entry in her diary at this time was “No Vote No Census Clemence Housman.” Along with other WTRL members, Clemence refused to pay taxes on her rental property in 1911, and was admonished in a government letter in July, to which she replied that she was on holiday and unable to pay taxes. Finally, on September 29th, the tax authorities caught up with her, and she was arrested from her Kensington house. The suffrage community gathered at her house to show support, and Laurence himself escorted her to Holloway Prison. Immediately after her incarceration, Clemence petitioned the home office explaining her reason for alluding taxes, that she felt that she had “personally fulfilled a duty, moral, social and constitutional, by refusing to pay petty taxes into irresponsible hands.” At this time, Laurence commented to the press: "when they give her her freedom, she will do it again until representation has been granted." Clemence was released from Holloway quietly on 6 October, an event that attracted considerable press because of the position of her and her family within the artistic and suffrage communities. A special cable to the New York Times called Clemence a "Suffragette Martyr" (Liddington, Vanishing for the Vote; "Suffragette Martyr," The New York Times). |

Emily Hunsberger | ||

| 17 Jun 1911 |

Women's Suffrage Procession at Coronation of George V The "From Prison to Citizenship" banner at the Women's Coronation Procession, London, 1911. Photo by the Museum of London/Heritage Images/Getty Images. In this famous suffrage procession marking the Coronation of George V, the banner designed by Laurence and created by Clemence in 1908 for the Kensington Women’s Social and Political Union made one of its numerous appearances in public parades. The striking banner, “From Prison to Citizenship,” features the suffragist colours, depicting a white figure on a purple background, decorated with green vines. The design was so popular it was also incorporated into a postcard for wider distribution. Clemence personally enacted this slogan later in 1911, when she spent a week in Holloway Prison for refusing to pay property taxes until she was granted full citizenship. Her act of civil disobedience did not grant her full citizenship, but it did add strength to the movement. Some women got the vote in 1918, but it took until 1928 for universal female suffrage to be achieved in the United Kingdom (Liddington, Vanishing). |

Lorraine Kooistra | ||

| Jun 1901 |

Hobhouse report on Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 30 Nov 1900 |

Death of Wilde

ArticlesEllen Crowell, “Oscar Wilde’s Tomb: Silence and the Aesthetics of Queer Memorial” Related ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 17 May 1900 |

Siege of Mafeking lifted

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Oct 1899 to 31 May 1902 |

Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 18 Jul 1899 to 2 Aug 1899 |

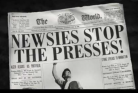

The Newsboys Strike of 1899

Hicks, Greg. “University of North Carolina at Asheville. an Uncivil War: The New York City Newsboys Strike of PDF Free Download.” University of North Carolina at Asheville. An Uncivil War: The New York City Newsboys Strike of PDF Free Download, https://docplayer.net/34730531-University-of-north-carolina-at-asheville.... Newsboys' Strike of 1899 Explained, Everything.Explained.Today , https://everything.explained.today/Newsboys%27_strike_of_1899/. |

Mackenzie Fischer | ||

| 14 Spring 1897 to 1933 |

The Rise of Gay RightsThe first gay-rights organization that was founded and recorded in history was in Berlin, called the Scientific-Humanitarian Commitee or Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee; WhK in German. It was founded in 1897, on the 14th or 15th of May, which was four days before Oscar Wilde's release from prison, and shut down in 1933. The founder of the Scientific-Humanitarian Commitee was Magnus Hirschfeld, who opened an Institute for Sexual Science in 1919, which was anticipated by decades of other scientific centres that specialized in sex research. Another notable thing that he did was sponsor the World League of Sexual Reform in 1928. Original members of the WhK included Hirschfeld, publisher Max Spohr, lawyer Eduard Oberg and writer Franz Joseph von Bülow, Adolf Brand, Benedict Friedländer, Hermann von Teschenberg and Kurt Hiller also joined the organization. There was a brief split in 1907, and In 1929, Hiller took over as chairman of the group from Hirschfeld. At its peak, the Scientific-Humanitarian Commitee had branches in approximately 25 cities in Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands. The Scientific-Humanitarian Commitee inspired many gay-rights organizations that came after it. Henry Gerber, who was a German Immigrant that served in the U.S. Army during World War I, was inspired to create his own gay-rights organization in 1924 called the Society for Human Rights, and it is considered the first documented gay rights organization in the United States. It was a very small group, but they did publish a few issues of a newsletter called “Friendship and Freedom,” and that is known as the country’s first gay-interest newsletter. The Society for Human Rights was very short lived and disbanded in 1925 after police raids. After that there were many organizations that came to be such as the Mattachine Society, founded in L.A. in 1950 and is regarded as the first viable U.S. gay rights organization. Also the Daughters of Bilitis, founded in San Francisco in 1955 as the first U.S. lesbian organization. Encarnación, Omar G. “Gay Rights: Why Democracy Matters.” Journal of Democracy, Johns Hopkins University Press, 14 July 2014, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/549501/summary?casa_token=pFORmtmjcrgAAAAA%3AX9OojUdlp9XRFptTfbGHlk6Zkx4-3OqX7EkwTXcttL2s1Emd-OO0nmFSZ0yiFajqUTeQdE33. History.com Editors. “Gay Rights.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 28 June 2017, https://www.history.com/topics/gay-rights/history-of-gay-rights. “Gay Rights Movement.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/gay-rights-movement. “Scientific-Humanitarian Committee Information.” WISSENSCHAFTLICH-HUMANITäRES KOMITEE - Encyclopedia Information, https://webot.org/info/en/?search=Wissenschaftlich-humanit%C3%A4res_Komitee. |

Jessica Moya | ||

| Apr 1895 to May 1895 |

Trials of Oscar Wilde

ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 14 Aug 1885 |

Criminal Law Amendment Act

Related ArticlesMary Jean Corbett, “On Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke, 1886″ Andrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Jun 1870 |

Civil suit against Edward John Eyre nullified

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Jun 1868 |

Edward John Eyre acquitted

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 15 Aug 1867 |

Second Reform Act

ArticlesJanice Carlisle, "On the Second Reform Act, 1867" Related ArticlesCarolyn Vellenga Berman, “On the Reform Act of 1832″ Elaine Hadley, “On Opinion Politics and the Ballot Act of 1872″ |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Apr 1867 |

Nelson and Brand charges dismissedA Middlesex grand jury at London’s Old Bailey criminal court dismissed charges brought by the Jamaica Committee against Colonel Abercrombie Nelson and Lieutenant Herbert Brand for the murder (via illegal court martial) of George William Gordon at Morant Bay, Jamaica in October 1865. The trial was a result of the Morant Bay Rebellion of 11 October 1865. Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 27 Mar 1867 |

Edward John Eyre indictment hearing

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Feb 1867 |

Trafalgar Square demonstrationMajor Reform League march and demonstration in Trafalgar Square, London on 11 February 1867. Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 2 Jul 1866 |

Hyde Park demonstrationHyde Park Demonstration of the Major Reform League on 23 July 1866. After the British government banned a meeting organized to press for voting rights, 200,000 people entered the Park and clashed with police and soldiers. Related ArticlesPeter Melville Logan, “On Culture: Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy, 1869″ |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Dec 1865 |

“Jamaica Committee”

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Oct 1865 |

Morant Bay Rebellion

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 2 Oct 1865 |

George William Gordon executedGordon, a Jamaican former slave and elected member of the Jamaica House of Assembly, is executed by hanging after a court martial condemns him to death for his alleged role in encouraging the Morant Bay rebellion. Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 23 Nov 1861 |

Birth of Clemence Annie HousmanClemence Annie Housman was born in Bromsgrove, England, on November 23, 1861. Saint Clement’s Day in the liturgical calendar marks the traditional beginning of winter. Housman was the third child and oldest girl in a family of seven children, the eldest of whom was A.E. Housman (1859-1936), the poet. Clemence was very close to the second youngest of her siblings, Laurence Housman (1865-1959), with whom she lived and worked her entire life. In addition to writing novels, Houseman was a wood engraver and an activist in the feminist movement for female suffrage. (Oakley, Inseparable Siblings)

|

Lorraine Kooistra | ||

| Jun 1858 |

Sale of the final piece of Chartist propertyJune 1858 saw the sale of the final piece of Chartist property, definitively bringing to an end the efforts of the Chartist Cooperative Land Company. The Chartist Land Company was a large-scale, explicitly political version of freehold societies. Conceived by the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor in 1842, the Company, like freehold societies, purchased large tracts of land through subscriptions and then sold smaller parcels to subscribers. It attempted to re-create village life by building cottages, hospitals, and schools, and setting aside one hundred acres for common use. Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 10 May 1857 to 20 Jun 1858 |

Indian Uprising

ArticlesPriti Joshi, “1857; or, Can the Indian ‘Mutiny’ Be Fixed?” Related ArticlesJulie Codell, “On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911″ |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Aug 1851 |

Chancery Court orders closing of O’Connorville

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 29 Spring 1851 |

“Ain’t I a Woman?” Speech at the Ohio Women’s Rights ConventionOn May 29th, 1851, Sojourner Truth, an abolitionist and women’s rights activist, delivered her famous “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. This convention was one of many that brought together a variety of activists who later helped to win the passage of the 19th amendment. The activists at this convention were inspired by the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments created at the Seneca Falls convention of 1848. This Declaration described women’s grievances and demands for their rights to equality as U.S. citizens, and the conversation continued in Akron, Ohio. The Ohio Women’s Rights Convention is most well known for being the venue in which Sojourner’s “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech took place. Though there are different versions of her speech, one published a month after the speech was given, by Reverend Marius Robinson, and one twelve years after the speech was given, published by Frances Gage, both touch on the intersectionality that exists between feminism and anti-racism. In Gage’s inaccurate transcript, Truth says “I think that betwixt the Negroes of the South and the women at the North all talking about rights, these white men going to be in a fix pretty soon.” In Robinson’s historically correct transcript, Truth says “But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between-a hawk and a buzzard.” Both versions of Sojourner Truth’s speech present the idea of white feminists and black feminists working together to simultaneously defeat the patriarchy and abolish slavery, rather than to let white feminism drown out black women’s voices. Podell, Leslie. “Compare the Two Speeches.” The Sojourner Truth Project, www.thesojournertruthproject.com/compare-the-speeches/. History.com Editors. “Seneca Falls Convention.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 10 Nov. 2017, www.history.com/topics/womens-rights/seneca-falls-convention. “Ain't I A Woman?” Learning for Justice, www.learningforjustice.org/classroom-resources/texts/aint-i-a-woman. |

Arden Woodall | ||

| Dec 1849 |

Carlyle's "Negro Question"

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 1 Jul 1848 |

Trial of Chartist leaders

The summer of 1848 witnesses violence as Chartist leaders are arrested and secret plots against the government are infiltrated. By the end of August, after the arrest of several hundred Chartists and Irish Confederates, the movement for violent uprising in England is broken. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

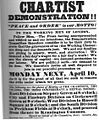

| 10 Apr 1848 |

Chartist Rally, Kennington

Led by Feargus O’Connor, an estimated 25,000 Chartists meet on Kennington Common planning to march to Westminster to deliver a monster petition in favor of the six points of the People’s Charter. Police block bridges over the Thames containing the marchers south of the river, and the demonstration is broken up with some arrests and violence. However, the large scale revolt widely predicted and feared fails to materialize. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 17 Aug 1846 |

Opening festival for O’Connorville

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Apr 1846 |

Formation of the Chartist Land Company

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |