Gallery Introduction

Charles Dickens’ classic book Hard Times weaves a story rich in anti-Utilitarian sentiment. The book, while detailing the lives of numerous characters, follows the Gradgrind family and their devotion to Facts in the industrial settlement of Coketown. Although the Coketown workers (nicknamed the “Hands”) greatly contribute to the town’s success, the Gradgrinds acknowledge them as a collective rather than individuals. In Chapter 6 of Book 2, Louisa Gradgrind comes “face to face with anything like individuality” in relation to a Hand when visiting Stephen’s shabby home (Dickens 160). Louisa comments how she only saw the Hands as “toiling insects” that went to and from their “nests” (160). In Victorian London, people of the upper crust also viewed the lower classes in much the same way. This exhibit focuses on artistic depictions from the Victorian era of the working class.

Jamie W. Johnson details how the working classes were artistically depicted in her article “The Changing Representation of the Art Public in ‘Punch’”. In magazines, such as Punch; or the London Charivari, the illustrations often portrayed the workers “in relationship to the dominant classes” and as a “philanthropic cause for the middle classes” (274). In essence, the poor laborers were only depicted as a generalized group, distinguishable by their differences to the other classes. Rarely would they have their true identities reflected back at them, as artists were usually those of the middle and upper classes. How did Victorian artists encourage or critique the idea of the working class as a collective rather than individuals?

The following images are an attempt to answer this question. These four pieces include two illustrations from Punch and two famous paintings of the working class. While three of these pieces show the workers as a generalized group, the final painting represents a real woman and her individual suffering. Peruse through the gallery to see how Victorian artists addressed the discourse around the worker and his identity.

Works Cited:

Johnson, Jamie W. “The Changing Representation of the Art Public in ‘Punch’, 1841-1896.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 35, no. 3, 2002, pp. 272–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20083889. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

Dickens, Charles. Hard Times. Wordsworth Editions, 1995.

Images in the Gallery

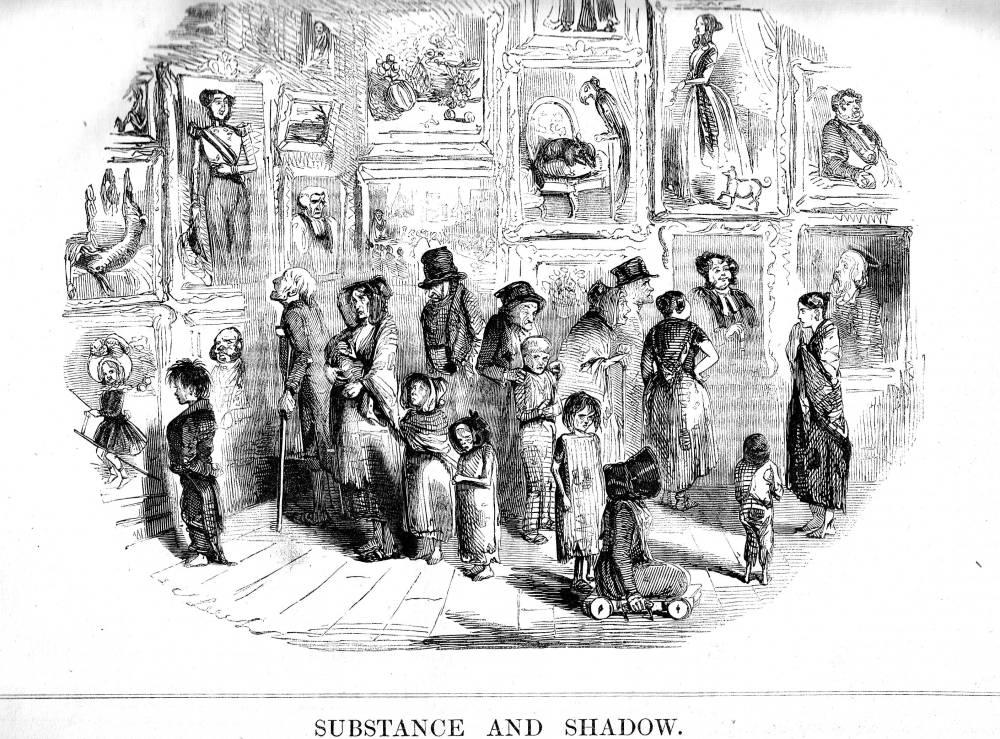

Fig. 1. Leech, John. “Substance and Shadow.” Punch; or, The London Charivari, 15 July 1843. Victorian Web, https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/leech/98.html.

Punch; or, The London Charivari was a British magazine established in the 1840s, edited by Mark Lemon, for the working classes. The outlet critiqued and satirized the government elites and their ignorance to the struggles of the poor. John Leech was an illustrator who greatly contributed to the success of Punch through his politically charged cartoons and caricatures. This Leech cartoon, known as one of the first ever political cartoons, was drawn for Punch’s July 15, 1843 edition. The image shows a group of impoverished working class adults and children, some with physical disabilities, studying individual portraits of upper class citizens in a Royal Academy exhibit. Notice how the paintings are evenly lit, while the group of workers are casting shadows on the floor. Leech is implying that the poor are mere “shadows” who go unnoticed and forgotten by society. The poor are not privileged enough to have their own portraits and be seen as individuals but are, instead, lumped together into a group. In contrast, the wealthy are of “substance” and are individualized through their portraits. Similarly to how Louisa in Hard Times does not connect individuality to the workers, Leech criticizes the rich for refusing to view the poor as anything other than their financial standing.

Fig. 2. Brown, Ford M. “Work.” 1852-65. Victorian Web, https://victorianweb.org/painting/fmb/paintings/hikim2.html.

Ford Madox Brown was a French painter known for his social realistic figures and landscapes. From 1852 to 1865, Brown labored tirelessly on his masterpiece, Work, which depicts various Victorian classes of workers in various occupations. In contrast to Leech’s “Substance and Shadow” cartoon, the lower class laborers doing intense labor are fully lit by the sun, while the upper class workers standing in idleness are enveloped in shadow. Brown uses light within the painting to suggest the morality of hard work and dedication, praising the poorer workers for their contributions to society. Although the workers are the subject of Brown’s piece, they are depicted as a collective group and idealized for their accomplishments as laborers. Upon close examination, one can tell that the faces of the workers are not very detailed, yet their physical bodies and activities are. Just like the “Hands” of Coketown, the workers are only acknowledged for what their bodies can do and not for their individual personalities or minds. Despite Brown’s good intentions with this piece, Work only upholds the rich’s view of the poor as disposable bodies who make them more money.

Fig. 3. Leech, John. “Specimens From Mr. Punch’s Industrial Exhibition of 1850.” Punch; or, The London Charivari, 1850. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/24743508.

The above cartoon is another work by illustrator John Leech for Punch; or, The London Charivari in 1850. In it, two wealthy men dressed in their Sunday best are attending the Industrial Exhibition. The “specimens” are none other than people of the working class entombed in glass with signs, such as “An Industrious Needle-woman” and “A Labourer Aged 75” above their heads. Notice how the workers’ identities are limited to their occupations, as if they are not individuals with their own lives. The glass represents how these laborers are trapped by the roles society has given them and are only valued for their physical labor. Even the word “specimen” emphasizes the dehumanization of workers, as the term would usually apply to an animal. Similarly, Louisa in Hard Times compares the workers to “toiling insects” like “ants or beetles” who swarm in the streets to get to their “nests” (Dickens 160). Leech is commenting on the rich’s disconnection from reality, as they only interact with the poor through superficial means. The Industrial Exhibition was an event which displayed the latest advances in machinery used in factories. Leech may also be criticizing how the poor were viewed as mere cogs in the machinery by those who benefited from their labor.

Fig. 4. Daniels, William. “The Song of the Shirt.” 1875. Victorian Web, The Song of the Shirt, William Daniels, 1875 (victorianweb.org).

For this painting, William Daniels was inspired by Thomas Hood’s poem The Song of the Shirt, written in 1843 for Punch magazine. The poem itself was based on a widowed seamstress, Mrs. Biddle, who lived in London with her two children. When she accidentally sold the clothes she made to a pawnbroker, instead of a central agent, she was convicted of a crime and sent to the workhouse. Like the poem, the painting tries to capture the suffering and hardships of a real, individual person. Notice how Mrs. Biddle is in her dingy home, surrounded by sewing equipment and is resting her head in her hand, as if she has been interrupted in her work and is contemplating her life. You can tell in her eyes that she is in anguish. Daniels is revealing the moments in between labor, how the worker’s life should not be glorified (like Work) nor limited by their jobs. Just like Louisa’s visit to Stephen Blackpool’s home in Hard Times, the painting is exposing its viewer to the dwelling of a poor worker and rejecting the depiction of said worker as a mindless drone. He is recognizing her value as a human being, not just a pair of hands.