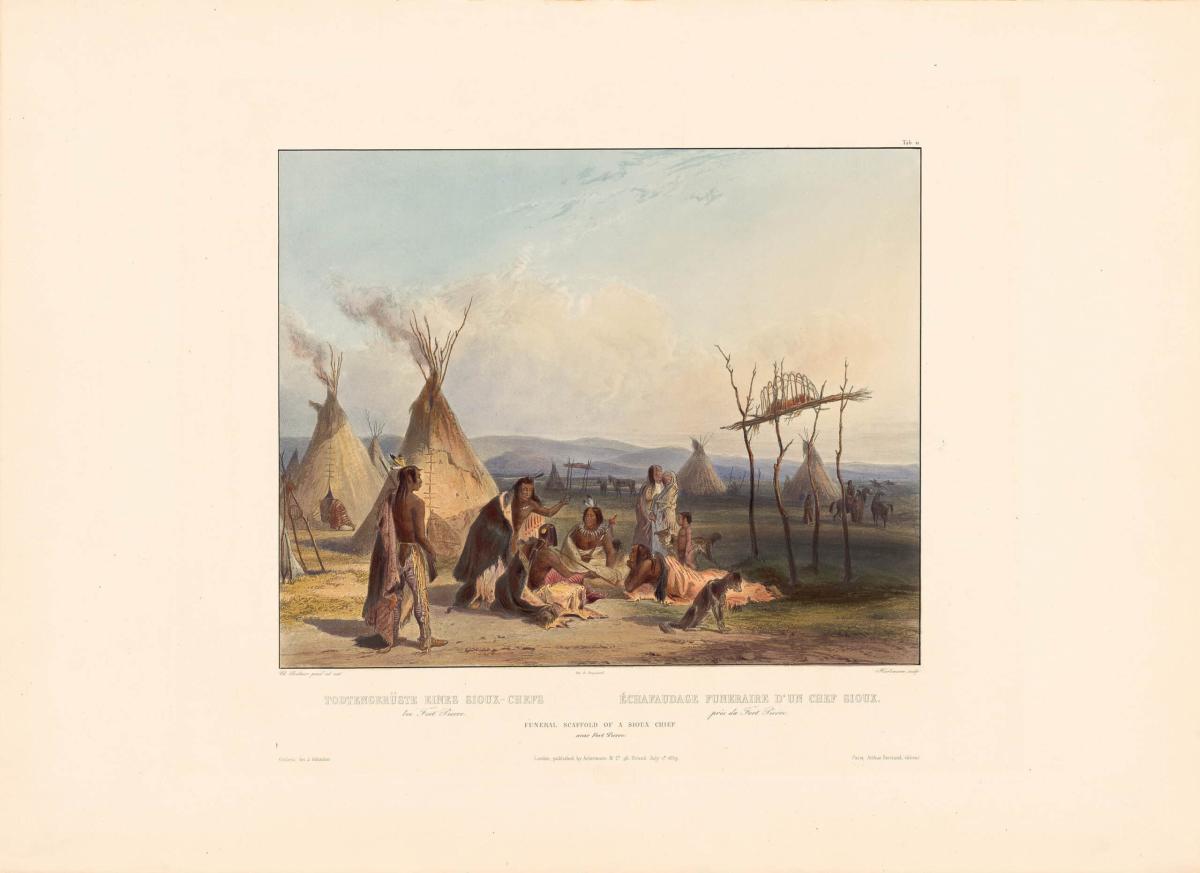

Pictured above is the funeral ritual of a Sioux Chief. The tribe is gathered together to mouran and celebrate the life of the Chief. Painted by Karl Bodmer in 1844, it records key beliefs and culture. This painting holds themes of life, death, and the differing views of the afterlife. Traditional Christian belief holds true that after death, one’s soul ascends to Heaven or descends to Hell. Regardless, they are to live eternally in bliss or torture under God’s rule. However, there are many different views of what occurs after death, each often holding religious significance (Campbell 551). Globally, there are various religions and spiritual guides that offer diverse ideas of the afterlife. Native Americans, who hold strong spiritual cultures, often have views of activity and an almost “second life” after death.

Although beliefs highly vary between different tribes, one such author, Phillip Freneau, recorded the differences between common Christian belief and the beliefs of a Native American tribe he had encountered. In observing and interacting with them, Freneau was able to put his comparisons down into words with his poem “The Indian Burying Ground.” Freneau, within American history, is an outlier in his kindness towards the Native Americans, who were still seen as savages at this time. With “manifest destiny” ongoing, tensions were high between Americans and Native American tribes. Despite this, Freneau was able to cooperate and learn about the different cultural beliefs that Native Americans held. Within “The Indian Burying Ground,” Freneau discusses the contradictions that he notices in popular Christian belief of immortality, and “the posture that we give the dead, / [which] Points out the soul’s eternal sleep” (Freneau 3-4). In the beginning of the poem, Freneau describes how Christian burial symbolizes eternal slumber, which seems to contradict the liveliness of immortality that is pictured for the afterlife. Freneau then goes on in the poem to compare this lying state to this native tribe’s rite of burying the dead in an upright, sitting position: “Not so the ancients of these land – / The Indian, when from life released, / Again is seated with his friends, / And shares again the joyous feast” (4-8). Rather than death being an end, one is instead “released from life,” as the natives believed that life was a bondage, with the activities of man continuing even after death. This wisdom holds the concept of death merely meaning a new beginning, rather than a true end. This belief takes mortality, which is often seen as a sad and somber event, and instead shows death as a milestone in the eternal progress of humanity: “…that in burial customs once more “The Child of Nature” (as he called the Indian race in another poem) had proved to be ‘the better man’” (Campbell 552). The culture of American Indians is as significant as the culture of Christians. All the cultures do have significance in the world. And instead of frowning at something different, we should acknowledge the diversity- in people, in customs, in language, religion and culture.

Works Cited:

Bodmer, Karl. Funeral Scaffold of a Sioux Chief near Fort Pierre. 1844. Wikiart.org, https://www.wikiart.org/en/karl-bodmer/funeral-scaffold-of-a-sioux-chie….

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Philip Freneau". Encyclopedia Britannica, 4 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Philip-Freneau. Accessed 21 March 2024.

Campbell, Harry Modean. “A Note on Freneau’s ‘The Indian Burying Ground.’” Modern Language Notes, vol. 68, no. 8, 1953, pp. 551–52. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3043342. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024.

Freneau, Phillip. “The Indian Burying Ground.” Poetryfoundation.org, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46094/the-indian-burying-ground. Accessed 18, March 2024.