Introduction

Industrial Towns were products of the Industrial Revolution, and the Revolution was a product of invention. Creative, technological advancements, intended to improve the world, contributed to rapid industrialism. Which entailed the creation of towns filled with factories where mass production, at all costs, was the only objective. In these towns, the 99%, or working class, became enslaved by machines meant to make their lives easier. Professional author and historian Mark Cartwright claims “noise, pollution, social upheaval, and repetitive jobs were the price to pay for labour-saving machines, cheap and comfortable transportation, more affordable consumer goods, better lighting and heating, and faster ways of communication”. The ebb and flow of supply and demand only took a greater toll on the working class, which led Victorian authors and artists to provide commentary on the world’s production-based priorities.

Through his book Hard Times, Charles Dickens gives readers a firsthand account of how he saw Industrial Towns in Victorian age Great Britain through his descriptions of the fictitious Coketown. It’s believed Dickens based Coketown on either Preston or Manchester for their similarities. In the book he paints the town as a monotonous place, through descriptions such as “time went on in Coketown like its own machinery: so much material wrought up, so much fuel consumed, so many powers worn out…” (Book 1, Chapter 14). It’s towns like these that were made possible by inventions. Inventions led to factories, which require people to operate, and factories led to cities to house all the workers. Inventions “transformed working life and everyday living for millions of people” (Cartwright). This gallery provides commentary and analysis of that progression.

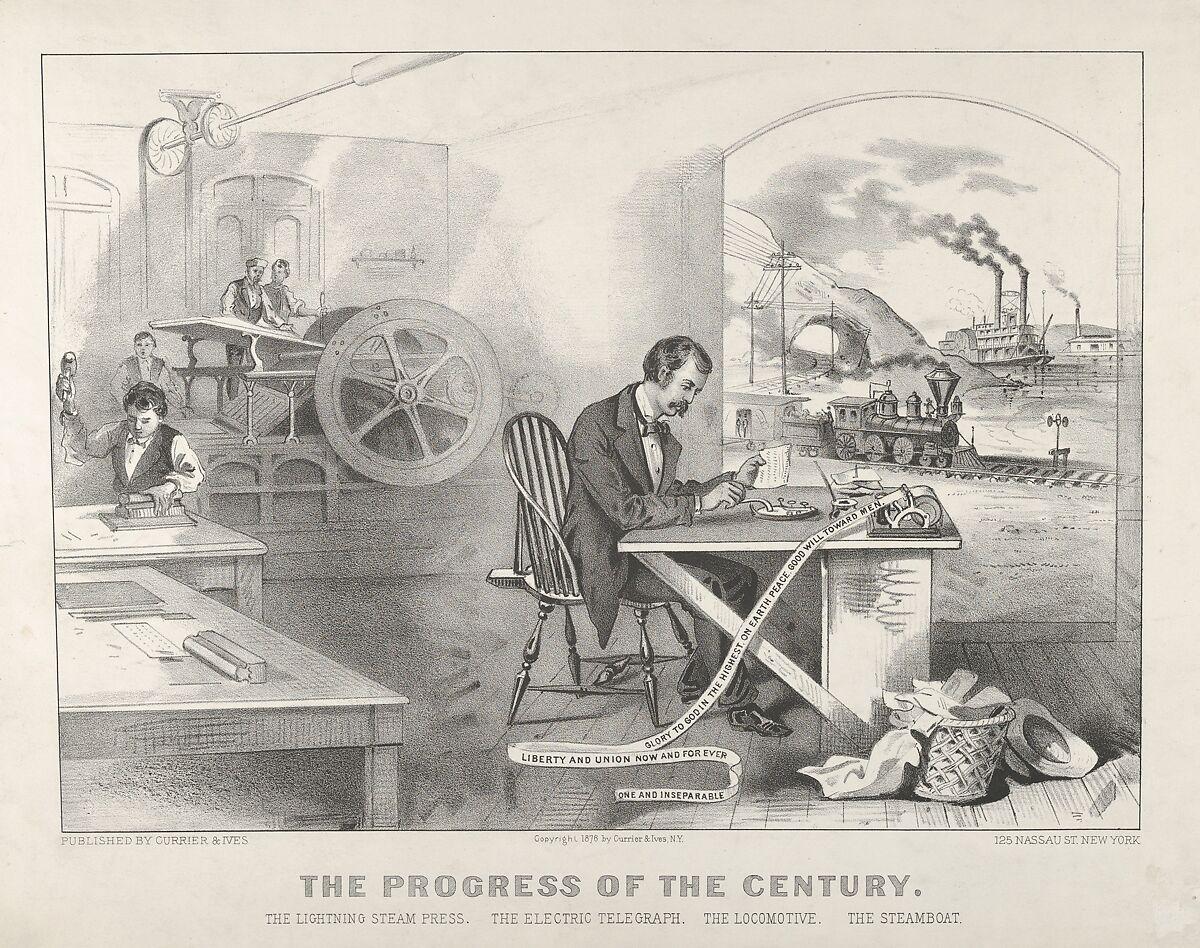

Look through the lens of George P. Landow to see a modern rendition of an industrial worker operating a mule spinner; an invention still being used today to weave threads. Witness the development of cotton mills across the pond, in Philadelphia where a new Industrial Town is beginning to transform its natural surroundings. Or check out a depiction of numerous transformative inventions through a lithograph, courtesy of the Met. Read through each picture’s accompanying description as you go to learn more about the creation of Industrial Towns, and what Dickens, Cartwright, and their creators have to say about them.

Work Cited:

Cartwright, Mark. “Top 10 Inventions of the Industrial Revolution.” March 20, 2023. Word History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2204/top-10-inventions-of-the-industrial-revolution/. March 30, 2024.

Images in the Gallery

Fig. 1. “The Progress of the Century – The Lightning Steam Press. The Electric Telegraph. The Locomotive. The Steamboat.” 1876. The Metropolitan Museum of Art website, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/659890?deptids=9&when=A.D.+1800-1900&ao=on&ft=industrial&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=3.

Printed by Currier and Ives, this lithograph depicts a few of the major inventions contributing to the industrialism of the Victorian age. There’s a clear intent for celebration, especially when including the message on the telegraph “Liberty and Union now and forever one and inseparable. Glory to God in the highest. On earth peace, good will toward men”. But this picture also contains more negative undertones when given more context. For example, depicted in the background is a train, a major development of the Industrial Revolution. Cartwright speaks to this development by stating how they “created a boom in production of coal (for fuel) and iron and steel (for rails, bridges, and trains)” and later adds that this boom created “a massive quantity of jobs” as well, thus further expanding the working class. The picture also includes a child working, which alludes to the use of child labor at this time. Dickens sheds light on this in Hard Times when regarding the Hands, or working class. He says, “the Hands, men and women, boy and girl, [went] clattering home”, which notes the common sight of child labor (Book 1, Chapter 10). A final note on this picture is that the man operating the telegraph machine, front and center, is both an adult and well-dressed. Alluding to his station in the workforce hierarchy and, as a result, his far less laborious desk job. Which shows how some inventions did in fact lead to more comfort, but only for a select few.

Fig. 2. Landow, George P. “Mule spinner creating cotton thread.” October 2004. The Victorian Web. https://victorianweb.org/technology/textiles/t2.html.

George P. Landow provides a rendition of a mill worker, here a figurine, during the Industrial Revolution in the Victorian age. The man is depicted as working on a spinning mule, one of many inventions contributing to the Revolution. Cartwright comments on this by stating “the textile industry in the British Industrial Revolution was transformed by machines” and later adds the shocking statistic that “in Britain in 1790, cotton accounted for 2.3% of total imports; by 1830, that figure had rocketed to 55%”. Dickens’ own fictitious Coketown was devoted to the textile industry. He comments on this throughout the text and, more specifically, in an explanation by character James Harthouse, who describes a man he met as “‘one of the working people; who appeared to have been taking a shower-bath of something fluffy, which I assume to be the raw material’” (Book 2, Chapter 1). This specific quote alludes to the working classes constant interaction with their trade. Which in this case is cotton. This photo also only shows a single worker operating this machine, despite its complexity. While factories and Industrial Towns are made up of many workers, that doesn’t mean their tasks are simple and straightforward. Especially with new inventions like the spinning mule and later the power loom.

Fig. 3. Rease, William H. “Joseph Ripka’s Mills. Manayunk, 21st Ward, Philadelphia. Manufacturer of All Description of Plain and Fancy Cottonades…” 1856. Printed by Wagner & McCuigan. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_09472/?r=-0.153,-0.062,1.212,0.751,0.

Here, across the Schuylkill River, is a picture of cotton mills in Philadelphia. There are many layers to this photo that, once peeled back, reveal how industrialism was taking the world in stride. As stated in the introduction, inventions contributed to the creation of factories, or mills, and therefore led to the creation of Industrial Towns. Here is an example of an Industrial Town being assembled. A mill has been built on the waters edge and other buildings are being put up nearby and on the hills beyond. In the bottom right corner two men, wearing top hats, look prepared to cross over to where the mills are. This could suggest a gravitation toward industrialism, as also evidenced by how there are increasingly more buildings closer to the actual mills. Dickens tells what to expect out of growing textile towns such as these in Hard Times. When discussing Coketown, a town dedicated to textiles, he says it “was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever” and later adds “it had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and a trembling all day long” (Book 1, Chapter 5). This is a fully developed Industrial Town, unlike the one in this image, but it tells of what’s to come. The uniformity of the buildings also depicts the monotony of industrialism and how one became part of the whole. Much like the workers who populated Industrial Towns.

Fig. 4. Dore, Gustave. “Over London – By Rail.” 1872. The Victorian Web, https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/dore/london/30.html.

This engraving, by Victorian age artist Gustave Dore, depicts the uniformity of industrialized London. The brick homes in the engraving extend endlessly into the distance. They’re all the same and reflect how the working class became identified as a collective in Industrial Towns, rather than individuals. This is reflected by Louisa Gradgrind’s judgement of the working class in Dickens story Hard Times. When she visits the part of town where working class people live, such as the apartments depicted here, it’s said “she had scarcely thought more of separating [the working class] into units, than of separating the sea itself into its component drops” (Book 2, Chapter 6). As for the brickwork displayed in the image, Dickens sheds light on this as well. When speaking about the fictitious Coketown, he says “nature was as strongly bricked out as killing airs and gases were bricked in” (Book 1, Chapter 10). There’s notably no sign of nature but many chimneys and smoke in Dore’s engraving, corroborating Dickens’ description of an Industrial Town. Not all parts of Industrial Towns were bad though. For example, Cartwright mentions how Great Britain was the first country to start using gas lights in cities. The modern equivalent would be streetlamps, which assist in seeing more clearly at nighttime. Cartwright notes that “by around 1820, London had 40,000 gas streetlights”. Such luxuries, however, are not seen in districts such as the one depicted by Dore. Which suggests that despite their contributions toward industrialism, the working class was denied many of its benefits.

Work Cited:

Dickens, Charles. “Hard Times.” 1854. Cove Studio, www.covecollective.org. March 30, 2024.