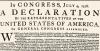

The Declaration of Independence, a document well-known across the world, is often regarded as the starting point for Americans to form their own identity. The document itself sets out to empower its people, which readers can see in iconic lines such as the following: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal...” (US 1776). While the declaration allowed the colonists to develop their own rights and freedoms over time, the immediate effects on the people were not as clear and life-changing—but they did give colonists of many backgrounds hope. The Museum of the American Revolution particularly points out the “unintended audiences” of the document, such as colonial women, people of African descent, and non-Protestants. The promise of “unalienable rights” (US 1776) would have been especially appealing to these groups, as it seemed to provide them with more power as individuals than they ever would have had anywhere else at the time. Revolutionaries of the time were also delighted to see their hopes for freedom begin to come to fruition.

Despite the hope that the Declaration brought to the colonists, many were concerned about the idea of independence from Britain. These colonists, often referred to as “loyalists,” wanted to instead remain loyal to the reign of King George III (“Big Idea 8”). Loyalists disagreed with the principles found within the Declaration of Independence and saw themselves as British citizens over anything the revolutionaries had been writing at the time. The Declaration directly calls the actions of King George out, much to the disdain of the Loyalists at the time: “... a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States” (US 1776).

Overall, however, most colonists were not focused on the Declaration of Independence; instead, they “simply hoped that they would escape the war without loss or suffering” (“Big Idea 8”). A war with Britain could have proven catastrophic for the colonists’ ways of life, so avoiding conflict was a hope that several colonists shared.

Works Cited

“Big Idea 8: After the Declaration: What Happens Next?” Museum of the American Revolution, www.amrevmuseum.org/big-idea-8-after-the-declaration-what-happens-next#:~:text=The%20Declaration%20of%20Independence%20served,colonies%20to%20demand%20those%20rights. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

Declaration of Independence, 1776.

Ortel, Johannes Adam Simon. Pulling Down the Statue of King George III. c. 1859, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fb/Johannes_Adam_Simon_Oertel_Pulling_Down_the_Statue_of_King_George_III%2C_N.Y.C._ca._1859.jpg