1870 Married Women's Property Act

Under the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act, coverture, which was “the legal doctrine that made two people legally one upon marriage,” was severely reduced (Ablow 1). Women were hereafter able to better access ownership of their own property without it immediately being subsumed into their husband’s estate upon marriage. There were many laws that led up to the passing of this act that slowly chipped away at the institution of coverture, which gave husbands all rights over their wives’ property, legal decisions, and even gave them sole custody of their children. At stake here is the very identity of women. The 1870 Act gave them the ability to act as autonomous agents, although Jill Rappoport points out that while women may not have legally had much power or influence under coverture and primogeniture (the tradition that dictated wealth pass on to the first son or closest male heir), women certainly had influence over their own husbands, often convincing them to act in their favor (3).

While Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre takes place many decades before the passing of the 1870 Act, Bronte would have seen some of the previous laws building up toward it. Most notably, as Rachel Ablow posits, would perhaps been the Custody of Infants Act of 1839, which gave women the ability to gain custody of their children under seven years of age (1). The rights of women under the institutions of coverture and primogeniture were beginning to come under scrutiny during the time that Bronte was writing, and many of the issues surrounding them are present in Jane Eyre. The novel deals with themes of marriage throughout.

The institutions of coverture is not particularly problematic for the novel’s protagonist, Jane, although if she had agreed to marry St. John, it might have become so. Instead, it is more of an issue for Jane’s love interest, Mr. Rochester. Rochester is bound in marriage to a woman he does not love, and, who by all appearances, is insane. The concept of “one flesh” in coverture, while typically and perhaps too simplicially seen as problematic almost entirely for women, applies too to Rochester and Bertha Mason, however much Rochester may wish otherwise. Rochester is bound to make decisions for his wife. Yes, he makes some arguably questionable decisions, but nevertheless, Bertha Mason’s essentially becoming his property binds Rochester to a life he detests. They are both victims of this institution that is only just starting to come into question and experience change at the time that the novel is written.

Works Cited

Rappoport, Jill. “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 7 Oct. 2018.

Ablow, Rachel. “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 7 Oct. 2018.

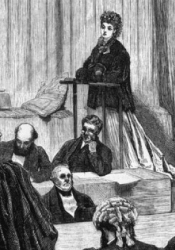

Image: http://www.intriguing-history.com/married-womens-property-act/