Jack the Ripper

** Content Warning: Descriptions of violence / gore **

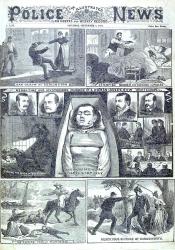

Jack the Ripper is infamous to this day for the brutal serial murders of women in the East End of London. From April 1888 to February 1891, eleven women were killed in the Whitechapel area of London. Of these eleven women in the Whitechapel murders file, five are known as the canonical victims of Jack the Ripper. Their names were (in order of death): Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. These five murders took place in the Whitechapel district in London, then known for its high crime rates and impoverished inhabitants. It was frequented with violence and was popular housing for criminals and prostitutes (Jones, Ryder).

The Ripper murders held similarities in the victims’ profiles and the ways in which they were killed. Each victim was impoverished, had work in prostitution, and lived in the Whitechapel area. The killer also attacked the women similarly: their necks and abdomens were mutilated, and they were usually disemboweled. Organs were often found missing or displaced from the body. Some newspapers refused to publish the detailed descriptions of the mutilated bodies because of how intense the scenes were. The murders quickly became an international phenomenon. Newspapers also questioned the police’s competence and the safety of the Whitechapel district. Although the murderer was never identified, the police force in that time had the disadvantage of not using detective skills found in modern society, and they had an undermanned force (Jones, Ryder).

One central theme in the texts we’ve been reading has been how people of low classes are neglected and ignored by those in power. Novelist Arthur Morrison described Whitechapel district as a place “whose trade is robbery, and whose recreation is murder . . . [where] fathers, mothers, and children watch each other starve” (qtd. in Ginn). James Grant described the slum conditions of East End “as if the wretched creatures were living in the very centre of Africa” (qtd. in Dyos). Based on these descriptions of the locale from people living in the late 1800s, the East End of London was certainly filled with people of the lowest classes in society; it was filled with people who were suffering from hunger, crime, unemployment, and an apathetic government. The destitute situation in Whitechapel and the surrounding areas did not enter the larger public mind until the Ripper murders began—when the cases were publicized around the country and world.

As mentioned previously, each of the Ripper victims had work in prostitution, engaging in criminal activity in order to support themselves. Megha Anwer notes, “The bulk of the Ripper photographs resemble criminal mug shots. . . . The effect can imply that crime is somehow resting immanently within the physiological contours of the victim herself, as if there were something in her appearance that led to her victimization. The prostitute thus becomes less the crime’s victim and more its provocation.” This observation indicates that the victims were being framed as though the attacks on them were to be expected because of their employment and history. Considering both the public opinion of prostitution and of the slums of Whitechapel, one safe assumption about the time is that people cared more about the public appearance of having a slum rather than the people living within them. Although there were certainly individuals concerned about people’s lives, the government may have not taken any action to prevent further events like this from happening if the murders were not reported so widely. I find it unlikely that the government was unaware of significant criminal activity within the capital city of the country. This idea also connects to another theme in the books we’ve been reading: the power of the rich to do as they please.

Bibliography:

Anwer, Megha. “Murder in Black and White: Victorian Crime Scenes and the Ripper Photographs.” Victorian Studies, vol. 56, no. 3, Apr. 2014, pp. 433–41. EBSCOhost, doi-org.ezproxy.uvu.edu/10.2979/victorianstudies.56.3.433.

Dyos, H. J. “The Slums of Victorian London.” Victorian Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, Sept. 1967, pp. 5–40.

Ginn, Geoff. “Answering the ‘Bitter Cry’: Urban Description and Social Reform in the Late-Victorian East End.” London Journal, vol. 31, no. 2, Nov. 2006, pp. 179–200. EBSCOhost, doi.org/10.1179/174963206X113160.

Jones, Richard. Jack the Ripper 1888, 5 May 2006, www.jack-the-ripper.org/. Accessed 08 Oct. 2022.

Ryder, Stephen P. and Johnno. Casebook: Jack the Ripper. 1996, www.casebook.org/index.html. Accessed 08 Oct. 2022.