Muscular Christianity & "Tom Brown's School Days"

"Muscular Christianity" is a term first used by T.C. Sanders whose work focuses on the intersection of Christianity and masculinity (namely manliness). Donald E. Hall summarizes Sanders's use of the term by defining muscular Christianity as "an association between physical strength, religious certainty, and the ability to control the world around oneself" (7). While the term “muscular Christianity” is more popular, the phrase “Christian manliness” was also popular during the Victorian era. The two phrases differ as many people thought the term “manliness” had a stronger association with physical and moral strength; however, “masculinity” ultimately became more popularized (Hall 9). Hall explains the Victorian men as profoundly insecure and afraid of the changing world. More specifically, muscular Christianity came as a reaction to the scientific, technological, and industrial advancements (8-9). In an effort to gain control, Victorian Christian men sought to achieve ultimate self control through toning the physicality of their bodies.

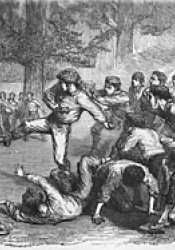

The idea of muscular Christianity was encouraged most significantly in Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s School Days, a novel published in 1857 and about a young boy, Tom, who goes to Rugby School. Andrew Richard Meyer explains the tenets of muscular Christianity expressed in Tom Brown’s School Days as “1) a man’s body is given to him (by god); 2) to be trained; 3) and brought into subjection; 4) and then used for the protection of the weak; 5) for the advancement of all righteous causes; 6) and for the subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men” (12). These six pillars of muscular Christianity point to the desire for control Victorian men experience as a result of the changes and advancements of the continually modernized world. Tenets five and six especially highlight the desire for control as they express desire beyond self-control. By encouraging the body to be used to advance Christian causes and subdue the earth, muscular Christianity extends beyond the individual life of those who practice it because it encourages and inspires the muscular Christian to control their surroundings. This control not only comforts the Christian who is afraid of change, but also reassures them of their righteousness in doing so. The image included in this post is an illustration from the French edition of Tom Brown’s School Days. It depicts the strength and violence associated with and encouraged by muscular Christianity.

Muscular Christianity can be found in Jane Eyre through the character Mr. Brocklehurst. Lowood teaches its students Christian ideals, but the connection to muscular Christianity resides in Mr. Brocklehurst’s violence. Mr. Brocklehurst’s hypocrisy also mirrors muscular Christianity as the focus and goal of this type of Christianity does not line up with the kindness and love encouraged in Christian doctrine. Like Mr. Brocklehurst, the muscular Christian seeks to control those around him (and I specifically choose the pronoun “him” because muscular Christianity was partially inspired to be a push back against women’s liberation) in violent ways which reassure his physical strength and dominance (Hall 48). Thus, muscular Christianity was less about spreading the word of God and more about using the word of God to validate the drastic measures taken to obtain power and control. This validation is found, as mentioned above, because the control is used to further God’s work through “the advancement of all righteous causes” (Meyer 12). Ultimately, muscular Christianity gave Victorian men, insecure because the world was changing faster than they could, the reassurance that they are in control of something and that that control is given to them by God to do God’s will.

Meyer, Andrew. “Contemporary American sport, muscular Christianity, Lance Armstrong, and religious experience.” 2006.

Hall, Donald E. Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age. Cambridge University Press, 2006.