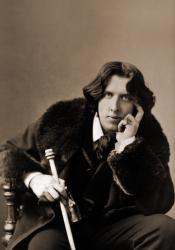

Oscar Wilde's Trial(s)

Oscar Wilde was involved in two significant trials during his lifetime. The first was initiated by himself: a libel trial against the Marquess of Queensbury, who sent him a public calling card that labeled him a “posing somdomite [sic]”. The Marquess was the father of Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. While this initial trial was not directly charging Wilde of indecency, it was related to the rumors that circulated surrounding his sexuality. Notably, he was questioned on his writing in The Picture of Dorian Gray, which had already been criticized in multiple sources “for its presumed intimations of homosexual criminality” (Bristow 43). Wilde was known for his wit in conversation as well as on the stand, and a failed attempt at a quick response likely aided in the result that the Marquess was deemed not guilty of libel, due to the court ruling that his accusations of sodomy were accurate (Bristow 44). The legal fees from this trial left Wilde bankrupt.

After the accusations of sodomy were ruled to be accurate, Wilde was arrested; though not on charges of sodomy itself. He was instead charged with “gross indecency,” which was classified as a misdemeanor rather than a felony. The maximum sentence for a misdemeanor was two years. While the phrase of “gross indecency” itself had historically been somewhat vague, it was amended in the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, making the charge “specifically about sex between men” (Elfenbein). Additionally, the misdemeanor charge required no proof of penetration, while a felony charge did. He was imprisoned for three weeks before he stood trial, being tried together with Alfred Taylor, a “well-known procurer of young men” (Elfenbein). Some of the witnesses questioned during the trial could only testify that Wilde had provided gifts to various young men or been seen coming and going from various hotels. Others were men that testified they had had intimate relations with Wilde. There were also “items of passionate correspondence” (Bristow 45) he had sent to Douglas, one of which was a poem that ended with the line, “the love that dare not speak its name” (Elfenbein). Ultimately, Wilde was convicted of the charge of gross indecency and sentenced to two years of hard labor in May 1895. He died in France in 1900.

Wilde’s trial was not the Victorian world’s first exposure to homosexuality. There were several scandals that involved sex between men in the late Victorian period, as well as “networks of places for men to hook up, from theaters and clubs to the train stations, parks, and museums” (Elfenbein) in London. There was already an established history of disapproval (to put it lightly) towards sex between men, and Wilde’s trial was so publicized because he was a popular author already known the to public.

Queerness has, in Western society, almost always been considered strange and immoral. It is quite literally in the name, and it is only relatively recently we have begun to reclaim the word. In regards to the texts in this class, I believe you can relate this to Count Fosco. While The Woman in White was written before Wilde’s trials, it still has aspects of the Victorian attitude towards gay men within it. Fosco is associated with femininity; specifically his elaborate clothes, love for animals, and fondness for pastry. While a large part of his strangeness in the novel comes from his foreign status, his femininity cannot be overlooked.

Works Cited:

Elfenbein, Andrew. “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web.

Bristow, Joseph. “The Blackmailer and the Sodomite: Oscar Wilde on Trial.” FEMINIST THEORY, vol. 17, no. 1, Apr. 2016, pp. 41–62. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700115620860.