The Reform Act of 1867

The Second Reform Act, sometimes referred to as the Great Reform Act of 1867, was a piece of voter-related legislation which granted the right to vote to certain working-class English and Welsh men, increasing the enfranchisement of men in Britain. The act followed on the heels of the Reform Act of 1832, which extended voting rights to British male property owners who met certain requirements. While the Second Reform Act doubled the number of eligible voters in England and Wales (Saunders 571), universal male suffrage was still not achieved. The act also galvanized a new movement for women’s suffrage due to its vague wording and set a precedent for prioritizing the male vote, regardless of class, over those of wealthier and more educated women.

The act held far-reaching implications for both conservative and liberal politicians at the time, as well as for the burgeoning women’s suffrage movement of the early Victorian period. The new qualifications for voting eligibility resulted in shifts in party demographics and numbers, and the vague wording of the bill inspired feminists and their allies to contest women’s disenfranchisement.

The bill itself was a conservative invention, introduced by the Tory Party in an attempt to expand their base. Thomas F. Gallagher argues that the bill was conservative in the sense that it was following a pattern of reform that had already been established and, for the most part, accepted by the populace (Gallagher 147). Rather than being a radical reform, it was a logical next step following the Reform Act of 1832. However, many conservative leaders still objected to the bill, feeling that it went too far. Lord Cranborne Robert Cecil allegedly saw the bill as a “surrender...of all the traditions that were sacred” to the Conservative Party (Gallagher 148). The strategy and overall goals of the bill have both been points of contention by scholars. While Gallagher characterizes the bill as a strategic and intentional move by a conservative government to acquire more party voters, others like Robert Saunders argue that the widespread enfranchisement which occurred was not the government’s intention. Saunders argues that the goal of each party was not to enfranchise as many voters as possible but rather to find “a safeguard against further additions” and calls the resulting influx of eligible voters an “irony of history” (Saunders 591).

The bill held significance for liberals as well, who had long been in conflict with conservatives regarding the issue of enfranchisement. Liberals had offered other reform bills and amendments before the 1867 bill was introduced, but conservatives had been reluctant to move forward. Some leftist politicians felt that the 1867 bill did not go far enough, one of which being John Stuart Mill, an outspoken radical who supported women’s suffrage. In his influential treatise Considerations on Representative Government, Mill argued that gender was as “irrelevant to political rights as difference in height or in the color of the hair” (Mill). In May 1867, he presented an amendment to the bill which would have included women in its language by changing the word ‘man’ to ‘person’, but he was not successful in getting the amendment to pass (Rendall 136).

The Reform Act of 1867 can be seen as a catalyst for an increase in activism regarding women’s suffrage in Britain, as the overt exclusion of women from the language of the bill galvanized feminists. Before the bill even passed, feminists worked to have women included in its language, signing petitions and contacting sympathetic MPs in an attempt to be heard. While the 1867 Act did obvious good by enfranchising over a million English and Welsh working class men, early feminists were frustrated with the restrictive wording of the bill. Some suffragettes began to argue that women’s enfranchisement and legal rights had been pre-established by older legislation which did not follow the same word choice as the 1867 bill, and a new movement of activism, which argued that women who met the property requirements of previous bills should be able to vote, began to gain traction. In 1868, feminist Lydia Becker started a campaign to register women who met the appropriate property requirements and over 5,300 Manchester women attempted to register (Barnes 511). Although these women were not successful in their attempts to enfranchise themselves, the discourse of “lost ancient rights” (Barnes 511) gained traction as a result of the 1867 bill, and it became increasingly common for feminists to argue that their legal rights had been previously implicitly established and then officially undermined by the wording of the bill. The Second Reform Act energized the women’s suffrage movement and resulted in mass organization by feminists. 1867 saw the Manchester coalition of suffragettes adopt a formal constitution, and later that year the Edinburgh National Society for Women’s Suffrage was formed (Rendall 139).

The Reform Act of 1867 was a landmark piece of legislation which simultaneously increased the British voting population to numbers never before seen and systematically excluded women from the process of enfranchisement, galvanizing a new movement of feminists and their allies who focused primarily on suffrage. A combination of conservative and liberal agendas, the 1867 Act paved the way for further enfranchisement and resulted in increased feminist activism in the back half of the nineteenth century.

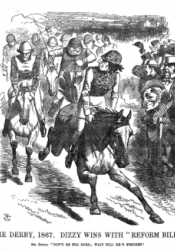

Image via Wikipedia.

Works Cited:

Barnes, Joel. “The British women’s suffrage movement and the ancient constitution, 1867-1909.” Historical Research, vol. 91, no. 253, 2018, pp. 505-527.

Gallagher, Thomas F. “The Second Reform Movement, 1848-1867.” Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 1980, pp. 147-163.

Mill, John Stuart. Considerations on Representative Government. Parker, Son, and Bourn, 1861. Project Gutenburg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5669/5669-h/5669-h.htm#link2HCH0008. Accessed 20 September 2020.

Rendall, Jane. “The citizenship of women and the Reform Act of 1867.” Defining the Victorian Nation: Class, Race, Gender and the British Reform Act of 1867, edited by Catherine Hall, Keith McClelland and Jane Rendall, Cambridge UP, 2000, pp. 119-175.

Saunders, Robert. “The Politics of Reform and the Making of the Second Reform Act, 1848-1867.” The Historical Journal, vol. 50, no. 3, 2007, pp. 571-591.