William Burke & William Hare Murder Spree

“Burking” is a verb meaning: “to murder, as by suffocation, so as to leave no or few marks of violence” (Dictionary.com). The term originates from William Burke, a 19th century serial killer who, along with his accomplice, William Hare, “murdered at least 16 people in Edinburgh, in order to sell their fresh bodies to the anatomist Robert Knox” (Tarlow 216). The murders took place in 1828 which was 77 years after the passage of The Murder Act which made it legal to dissect and study the bodies of executed criminals for the sake of anatomical research (Gül and Sahinoglu 128). The legacy of this act, of course, can be seen in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, as Victor primarily uses just such bodies to construct his creature. Eventually, though, the demand for corpses became greater than the supply, and the trade of the “Resurrection Men” (Evans 1190), who were essentially just graverobbers that sold the bodies they dug to anatomists, became rather lucrative.

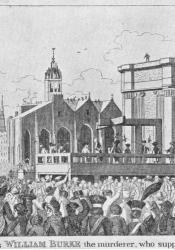

William Burke and William Hare “knew of grave robbers and would have robbed graves themselves; however, they found it too hard and dangerous” (Gül and Sahinoglu 130), so they instead opted to go on a murder spree. Said spree began when Hare’s renter died (of natural causes) and Hare and Burke decided to sell his body to Dr. Knox, who was one of Scotland’s most successful professors of anatomy at the time (Gül and Sahinoglu). After being paid for their first body and seeing how much money they stood to gain, the pair “[enticed] at least 15 unknown wayfarers into the lodging house, where they got them intoxicated and then smothered them” (Jenkins 1) and sold their bodies. Eventually, the disappearances of their victims began to attract attention, and they were caught. Their trial took place on Christmas Eve, 1828 (Evans 1190). Hare turned against Burke, testifying against him in exchange for immunity (Tarlow 216), and Burke was subsequently hung on January 28, 1829 (Evans 1190). Despite the unfortunate fact that Hare does not seemed to have paid for his crimes at all, karmic justice was at least served for Burke, when, following his execution, his body was “sent for anatomical dissection” and it was “[subjected] to the same fate as those of his victims” (Tarlow 216). These murders were especially significant, because they “caused a national furore of fear and anger, which became known as Burkophobia” (Richardson 161) and this “furore” eventually led to the passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832, “which decreed that the bodies of unclaimed paupers who had died in elderly care homes and hospitals be given to licensed anatomists for dissection” (Gül and Sahinoglu 128). Even this act, however did not rectify the body shortage, which would persist until WWII (Richardson 161).

Works Cited

“Burke.” Dictionary.com Unabridged, Random House INC, 2021, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/burking. Accessed 1 April 2021.

Evans, Alun. “William Hare the Murderer.” International Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 39, no. 5, Oct. 2010, pp. 1190–1192. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edb&AN=55117913&site=eds-live.

Gül, Senay and Sahinoglu, Serap. “Mystery of Anatomy: Robert Knox.” Anatomy: International Journal of Experimental & Clinical Anatomy, vol. 13, no. 2, Aug. 2019, pp. 126–135. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2399/ana.19.062.

Jenkins, John Philip. "William Burke and William Hare.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 27 Jul. 2011, https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Burke-and-William-Hare. Accessed 1 April 2021.

Richardson, Ruth. “Human Dissection and Organ Donation: A Historical and Social Background.” Mortality, vol. 11, no. 2, May 2006, pp. 151–165. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/13576270600615419.

Tarlow, Sarah. “Curious Afterlives: The Enduring Appeal of the Criminal Corpse.” Mortality, vol. 21, no. 3, Aug. 2016, pp. 210–228. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/13576275.2016.1181328.