Created by Maxx Freed on Wed, 12/15/2021 - 23:49

Description:

Introduction

Written by Wilfred Owen during World War One and published after his death, “Dulce Et Decorum Est” is one of the most famed anti-war works from this period of British history. In the poem, Owen presents a vignette depicting a group of soldiers who are attacked with chlorine gas. One soldier fails to secure his mask in time and succumbs to the gruesome effects of the gas. After presenting this horrific imagery, Owen calls out those who glorify the war:

“If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs …

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.”

The last line, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” translates to, “it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.” It is no wonder why Owen rejected this notion, as he experienced the horrors of WW1 firsthand. By calling this the “old lie,” Owen reveals his motivation for writing this poem, which can be seen as a reaction to the propaganda that targeted the British people during WW1. This propaganda attempted to promote pro-war sentiments while putting pressure on young men to enlist. Interestingly, the earliest draft of the poem was dedicated to Jessie Pope (Dunn), a well-known propagandist of the time. This supports this interpretation of his motivation. Owen’s rejection of this propaganda begs the question: how does art tell the story of war, how do we choose to depict it, and what does this have to say about our motivations, experiences, and values? “Dulce Et Decorum Est” openly invites us to think about these questions.

This series seeks to explore the imagery that Wilfred Owen took issue with. Included in the gallery are four propaganda posters that were produced and distributed in England during WW1. These posters all tell a different story about the war and those who fought in it. The series also explores how the messages of these posters compare to Owen’s depiction and attitudes towards war in “Dulce et Decorum est.

Work Cited

Dunn, Jennifer. “Manuscript of ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est.’” The First World War Poetry Digital Archive, University of Oxford,

ww1lit.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/exhibits/show/thefullenglish-910mw2/12.

Owen, Wilfred. “Dulce Et Decorum Est.” 1920. Cove Studio, NAVSA,

Images in the Serries

Fig. 1. Van Dusen, Howard “Knights of the Air.”1914-1918. Library and Archives Canada https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=3636756&new=-8585620139688743065

Produced by Howard Van Dusen and distributed sometime between 1914-1918, the poster shows two German soldiers who watch on as a Red Cross hospital is bombed. This poster belongs to a class of propaganda known as atrocity propaganda, which was used heavily in the British recruitment effort. These works attempted to exemplify and often exaggerate the wrongdoings of England’s adversaries with the hope of producing a sense of tribalism and outrage in the populous.

Notice how, very much like “Dulce Et Decorum Est,” the scene depicted is visceral and gruesome. In the background a hospital is on fire, actively being bombed by German planes. The use of Chlorine Gas in “Dulce Et Decorum Est” and planes in this poster play on the fears associated with the new technologies of the war. Also, notice the bloodied victims – presumably patients and nurses – who struggle to escape the fiery scene. Some lie on the ground, and others are clearly in distress. Many are dressed in white, portraying their innocence, which contrasts sharply with the dark military uniforms of the German soldiers in the scene. A similar confusion and mayhem is also seen in “Dulce Et Decorum Est,” where the gas quickly appears and takes the life of one soldier in a terrifying way.

However, while depicting a similar scene, the story told in this poster and in “Dulce Et Decorum Est” are quite different. In the poster, one German looks gleeful as the hospital burns, the other (presumably General Hindenburg), who led the German Army in WW1) looks on stoically. The bottom reads “Look Hindenburg! My German Heroes!” The flags on the hospital are quite large, perhaps intentionally prominent to illustrate that the Germans know they are targeting a hospital; it is not an accident, but rather an intentional act. This scene suggests that the Germans as uniquely evil and amoral. In contrast, Owen’s poem does not make any mention of the enemies (the importance of this is discussed further in the second annotation).

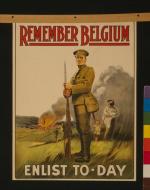

Fig. 2. Jenkinson, Henry. “Remember Belgium.” 1915. Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3g10881/

Produced by Henry Jenkinson and distributed by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee in 1915, this poster references “The Rape of Belgium,” a phrase used to describe the mistreatment of the Belgian people during the German invasion of the country. Like the previous poster, this is an example of atrocity propaganda. In the poster a mother and child run to the soldier for protection, presumably fleeing the town being attacked behind him. The use of a mother and child in this poster is important, as the English media circulated accounts of sexual assault against women and crimes against children during “the Rape of Belgium.” While the Germans did commit war crimes in Belgium, it is widely accepted that the British media took the opportunity to sensationalize (and perhaps fabricate) some accounts for the purpose of propaganda. The soldier in this picture is a hero, because, without him, the mother and her child would be victims of the evil Germans invading the town. He is the moral counterpart to the depraved soldiers in the previous poster. This idea that the British were righteous and moral, while the Germans were evil is not featured in Owen’s poem. It is not stated whether the troops are English, and whether the attackers are German. There is also no moral quality to the vignette, as the troops who are attacked by the gas are neither heroes nor villains. Perhaps this was intentional, and Owen probably understood that if he played into the reductive tribal viewpoint depicted in figure 1 and figure 2, he would detract from his message: it is more the act of war that is vile, rather than those who participate. Furthermore, he denounces this kind of imagery in his poem, as this depiction of the soldier as a righteous and admired figure is what perpetuates young people’s desire to become soldiers.

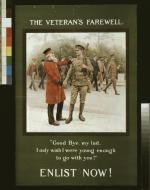

Fig. 3. Dadd, Frank “The Veterans Farewell.”1914. Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3g10925/

This poster, created by Frank Dadd for the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee in 1914, uses a different tactic than the previous two posters and exemplifies the spirit of the phrase, “dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.” Note the word patria, which roughly translates to country or homeland, but directly translates to land of one’s fathers. Implied in the term patria is that we are in debt to those who came before us and built, or went to war for the nation. This is an idea that probably resonated with the young men of Brittan, who may have been told war stories by their relatives or learned stories of war heroes in school. The older veteran depicted in the image, dressed in formal military attire, is presumably a figure who is greatly respected for his service. The veteran not only shows approval for the younger soldier’s actions, but he also longs to be in the younger man’s position, which sends a strong message to the young men who may be viewing this poster. It tells the viewer that there is glory to be found in following in the footsteps of your fathers and enlisting in the army. Yet, Owen suggests that those, like the veteran depicted in this image, take advantage of “children ardent for some desperate glory,” and that they are perpetuating lies.

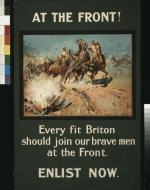

Fig. 4. “At the Front.” 1915. Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3g10904/

This poster, while one of three that depict the battlefield in the series, is unique in that the actual act of fighting is core to its persuasion. Produced by an unknown author and distributed by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, it depicts a cavalry unit engaged in battle. A bomb has just gone off in the foreground, but the blue skies and excitement on the first soldier’s face almost make it look like they’re on a thrilling adventure. Furthermore, the fact that they are riding horses, as opposed to marching, only serves to add to this excitement. This is an attitude that many young people hold, who play with toy soldiers, idealize battle, and may ultimately join the military. Owen tries to dispel this notion in “Dulce et Decorum est,” as he describes soldiers who are “bent double, like old beggars under sacks, knock-kneed [and] coughing like hags.” Then when the gas comes, they fumble with their masks in an unheroic fashion. Finally, there is the gruesome description of the death of the soldier who fails to put his mask on in time, “at every jolt, the blood, gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues. Here, he makes it abundantly clear that war is not a fun game to play, as this poster suggests. It is a vile struggle, where you must kill or be killed, and where you see unimaginable things such as a fellow soldier succumbing to chlorine gas.