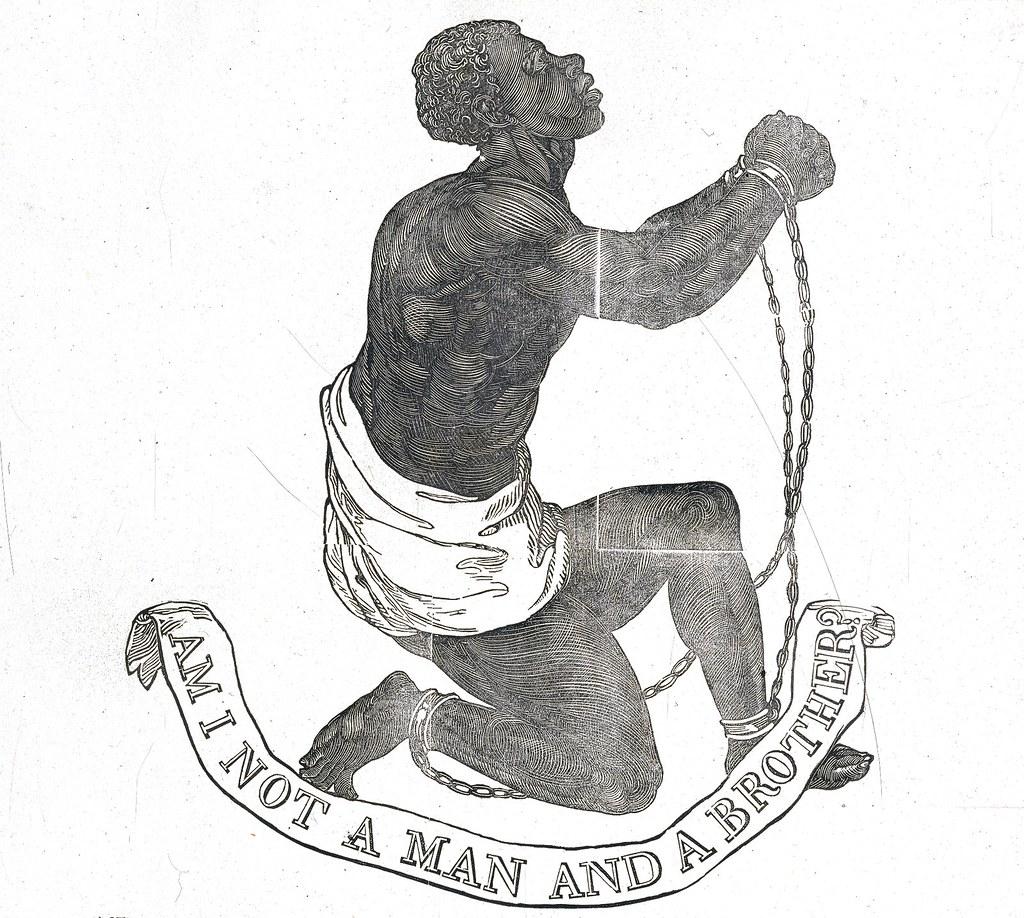

“Am I not a Man and a Brother?” was first produced by Josiah Wedgwood in 1787 as a medallion, roughly fifty years before the abolition of slavery in England. Of the image, University Professor John Barclay proclaims, "The slave in chains is kneeling in appeal to an unseen authority, evoking the emerging British self-image as a benevolent nation, committed to freedom and endued with the power to change the lives of others. … Both the quesion and its exact terms are important: it invites us to see this figure not as a ‘brute’, not as a ‘heathen’, not as a ‘savage’, now even as a ‘Negro’, but as a Man (a fellow human being) and a Brother (a term with multiple associations) (2)."

This kneeling figure in turns invites not aggressive behaviors, but paternal association, invoking the reader and looker to connect emotionally with the enslaved (3). “The image was widely reproduced during the late eighteenth century, appearing on crockery, snuffboxes, and jewelry, becoming a fashionable accessory among English abolitionists'' (1). Being so heavily and successfully propagated, Benjamin Franklin himself wrote of the image’s success as, “equal to that of the best written Pamphlet, in procuring favour to those oppressed People” (1). Franklin was not the only American influenced by the slogan. Ex-slave William Wells Brown wrote a poem in response to the plea saying:

Am I not a man and a brother?

Ought I not then to be free?

Sell me not one to another

Take no thus my liberty.

Christ, our Saviour

Died for me, as well as for thee. (2)

The poem only deepens the simple cry, “Am I not a man and a brother?” and echoes the sentiments and longing to be treated as equals.

In response to the propagandic image, Peter Peckard wrote, “Am I Not a Man? and a Brother? With All Humility Addressed to the British Legislature. His involvement in the abolitionary movement reached full fruition after having heard of the tragic Zong incident in 1881. In his article, Peckard makes a stance on humanity and starts his arguments with the powerful words, “the Traffick in the Human Species is destructive of the one, and contradictory to the other, and therefore is not justifiable by any Human Institution” (4). Throughout the work, he consistently derails common beliefs and excuses as to how the enslaved people were indeed of the human race and therefore demanded the respect associated as one.

He first starts his argument with, “even supposing the Negros to be Brutes, the benevolent spirit of religion teaches us that a truly righteous man is merciful to his beast, and that they are entitled even in this view to a treatment far different from that which they received at our hands” (4). In essence reiterating that even if the Africans were to in reality be identified as animals, the treatment of such animals would have been described as abominable and that no creature deserved to be treated as such. Other arguments alluding to the Africans as being somehow only, part human, give way to Peckard’s assertions that only same-animal species could reproduce, and in the event that a white male were to reproduce with a black female, this alone negated any sense of the slaves being only part human from a scientific standpoint (4).

The words of Peckward and Brown cited here were only two out of many that were influenced by the image of the kneeling slave. This image, being only one step in the process to abolish slavery.

Works Cited:

(1)“‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" · SHEC: Resources for Teachers.” Social History for Every Classroom, https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/579.

(2)Barclay, John M. “`Am I Not a Man and a Brother?' the Bible and the British Anti-Slavery Campaign.” The Expository Times, vol. 119, no. 1, 2007, pp. 3–14., https://doi.org/10.1177/0014524607082907.

(3)McDaniel, Caleb. “Am I Still Not a Man and a Brother?” Historians Against Slavery, https://www.historiansagainstslavery.org/main/2014/08/am-i-still-not-a-…;

(4)Peckard, Peter. Am I Not a Man? and a Brother? With All Humility Addressed to the British Legislature. 1788.