Barbara Black has some opinions about the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Some of them are questionable and some are widely accepted. Her argument about the original Farsi poem being translated by Edward FitzGerald and sold as a gift book for decades centers around the words being sold and marketed as FitzGerald’s work. The use of the poem as a gift book is inherently Orientalist in Black’s eyes. We can no longer read the poem at its face value, and instead must jump through hoops in order to get a clear reading that's free from Orientalist views and the eventual fascination with the Orient, specifically Persian culture and the Farsi language. Can we as a society even read the poem as “just a poem” anymore?

While the renowned translator FitzGerald only translated the words, which have been the cause of some scrutiny themselves, the illustrations are all different from version to version, and must be analyzed through each individual illustrator. The artist Willy Pogany illustrated my version from 1909, a very different world from the one we are living today, and on the flip side, a very different world from FitzGerald’s 1859 original translation. FitzGerald lived in a time that the fascination with the orient was being kicked off, largely thanks to the publication of 1001 Arabian Nights, and his work was shrouded in the Orientalist attitudes towards the East and Middle-Eastern cultures. The concept of Orientalism is defined by oppression and the desire of the West to stay in power above the East, and there are plenty of versions and examples of other art from this time period that are simply Islamic designs and rather than trying to stay superior, are actually interested in the culture and aim to present an innocent fascination. It is at this point that I began to consider the differences between being “curious” and “a curiosity”, the former being concerned with intellectual growth and knowledge, and the latter being concerned with capitalist attitudes and “othering” of something unknown to the viewer.

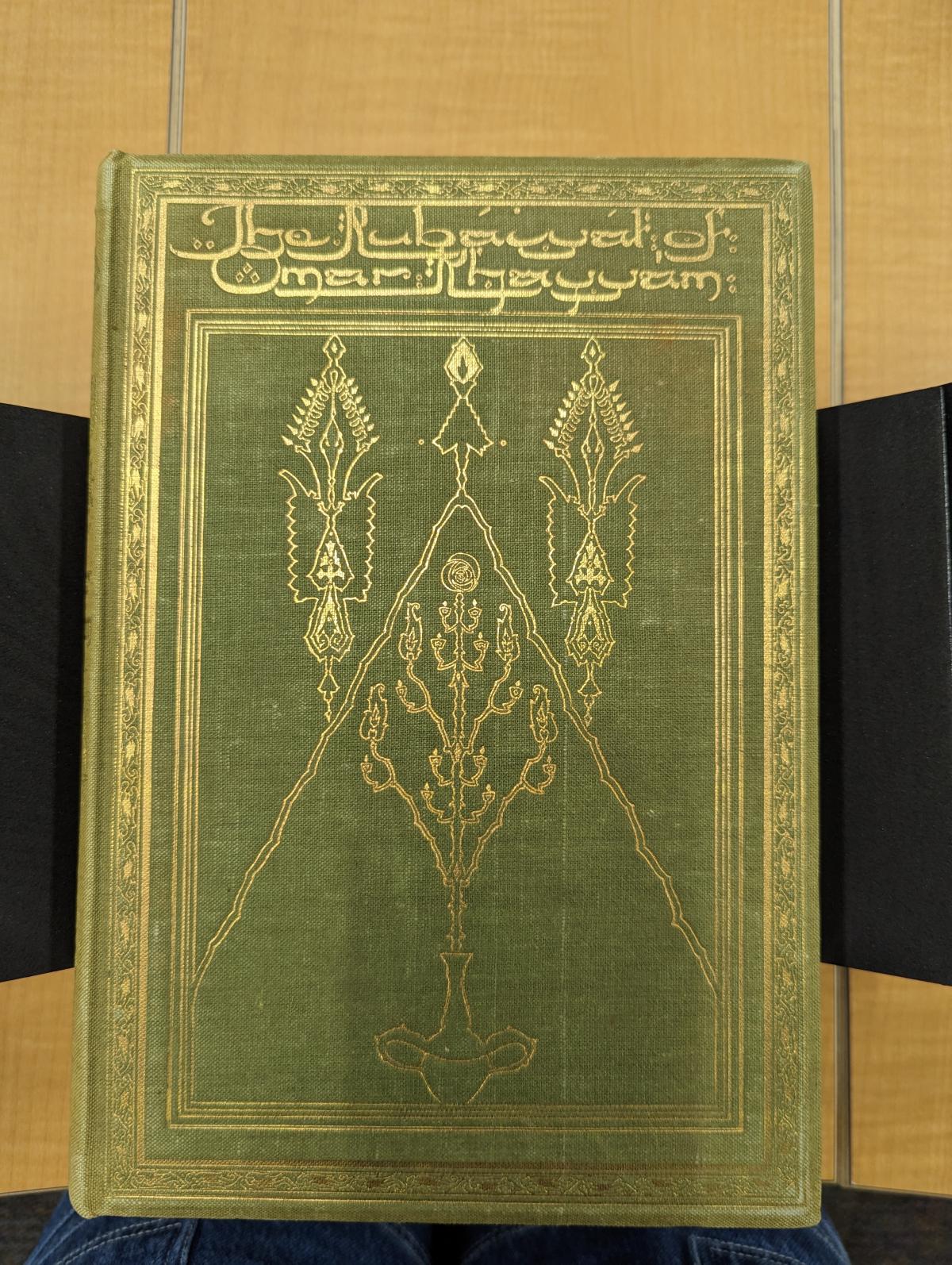

My particular version of the poem is a large size, one that can easily be seen decorating coffee tables and display cases. We all subconsciously “judge a book by its cover”, and my copy was no different. As a matter of fact, the cover sent my “Orientalist” alarm bells ringing. We can see in the first image the faded green cover of the poem, and we can just make out “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam” in the flowing script. The letters, while English, are artistically rendered in a font that resembles Farsi, the original language of the poem. I was, and still am, uncomfortable with the design of the title; it still feels like an attempt to placate an entire culture.

The second aspect I must address is the elephant in the room. Willy Pogany is a Hungarian illustrator. He is a white man who was hired to create a large repertoire of images to be used for the edition, and Pogany was likely also raised in the Orientalist culture, especially as a painter who was taught be masters who had also been taught and working in the same generational attitudes towards the Middle-Eastern countries. I could not shake the “White Savior” complex off of this edition, and still regard it as such. Pogany was a white man hired to “save” this gorgeous poetry from sure extinction, for who would read a poem by a Persian man? There is a dedication housed within the opeing pages of the edition in which Pogany thanks one of his mentors, a man named D. Julius Germanus, a Norweigan artist who is thanked for his knowledge of Persian art and is called "invaluable" by Pogany. Why Pogany didn't go to a Persian artst and asked for some guidance remains a mystery to me. In 1909, however, the notion of being hired to illustrate a version of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was a sign that an artist had "made it". My pre-concieved ideas about a "White Savior" in 2023 are much more sensitive than the politics in the era would have been. Since the poem had achived such heights of popularity, there were serveral, if not tens, if not hundreds of other illustrators doing the same work. This frame of mind depends on what era the poem is being viewed from.

For the third piece of evidence, I have selected an illustration from the edition that highlights the Orientalist imagery within the artwork. In image three, we can see a man and a woman in the throes, not of sexual ecstasy, but rather, of freedom of spirit. The man is fully clothed, and the woman is fully nude. The freedom of human beings to choose their lives to be filled with pleasure of all kinds is one of the major themes of the poem. The Orientalism of Middle-Eastern countries is often exotic and erotic, but these quailities are shown through appealing to the portrayed freedom, rather than depicting sexual acts. However, the extent of the European features does not end there. The two figures' hairless bodies are a form of infantalization, rendering the bodies of these people as young or innocent, which in and of itself is a technique of exotic art, particularly of the East.

The nude body has been a source of highly regarded beauty for generations, and this small piece of artwork is no exception. However, unlike the Roman marble statues, the woman’s lower genitals are curiously blurred. Her breasts are visible, but not her lower half. Was Pogany unsure if his edition would find itself in the hands of children? Was he uncomfortable with the detail of female sexuality? The man in the art is fully clothed, a detail that caused my eyebrows to scrunch in the suspicious misogyny, and the obviousness that the two humans depicted are white made me grit my teeth.

Black, Barbara J.. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. United Kingdom, University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Khayyam, Omar. (Edward FitzGerald). The Rubaiyat. London, United Kingdom, Vincent and Brooks, 1909.