Created by Lucia Theresa Wiegert on Tue, 10/15/2024 - 10:51

Description:

From Winnie-the-Pooh by A. A. Milne to Frog and Toad Are Friends by Arnold Lobel to Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White, readers love the literary animals of their childhood. But why are anthropomorphic animals important in children’s literature? To answer this question, one must examine the works of Beatrix Potter, who most notably gave children the loveable character Peter Rabbit in The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902). In the subsequent The Complete Peter Rabbit, Potter introduces readers to Benjamin Bunny, Squirrel Nutkin, and Jemina Puddle-Duck, yet her most famous work remains her first. With this brief introduction to the text, this case will now examine how Potter's anthropomorphic animals in The Tale of Peter Rabbit offer children relatable characters, simplified moral lessons, and inspiration for their imagination. It will also discuss the origins of the tradition of anthropomorphic animals and the effect on children’s literature today.

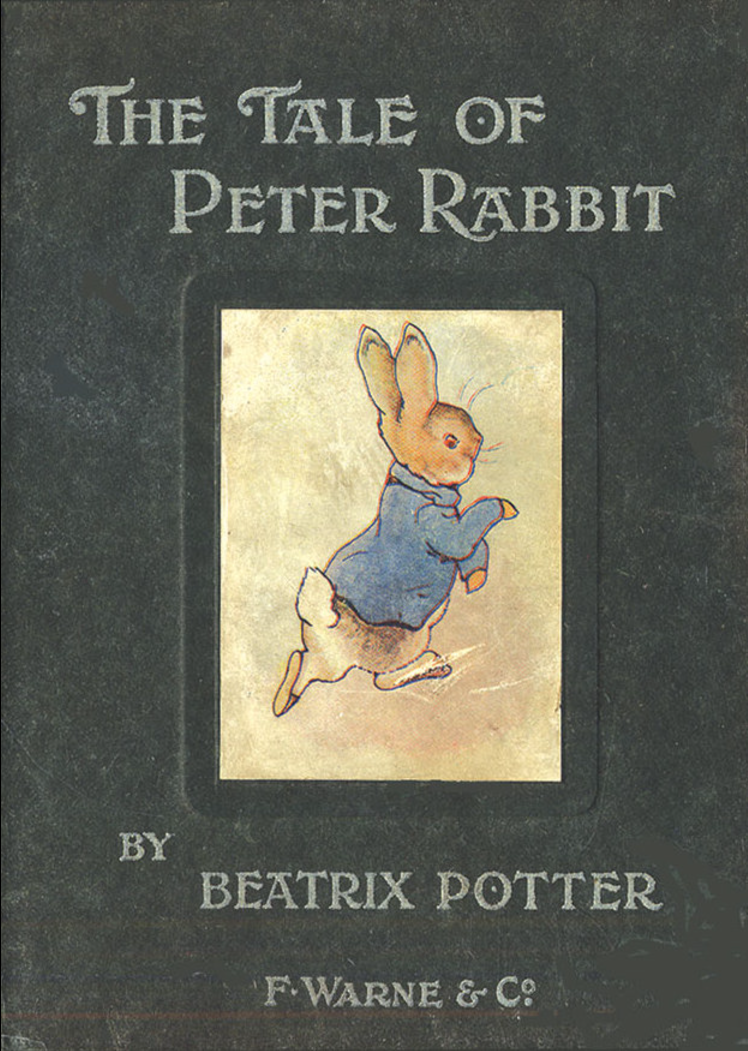

Beatrix Potter, Book Cover, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, 1902, Wikipedia. In The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Peter sneaks into Mr. McGregor's garden, and Mr. McGregor almost catches him. The book, written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, warns naughty children not to misbehave through anthromorphized rabbits; their actions have consequences.

Photograph of Beatrix Potter with Kep, Wikipedia, 2024. Helen Beatrix Potter was born on July 28, 1866, in Kensington, London. Her mother enjoyed painting in watercolor, while her father preferred drawing in pen and ink. Because of the artistic influence of her parents, Potter learned to draw from an early age by copying the works of other artists. In her 20s, she began drawing the plants and animals she observed under a microscope. In 1893, Potter wrote and illustrated The Tale of Peter Rabbit in a letter for the son of her former governess. The children’s book was revised and privately printed in 1901, and after being published by Frederick Warne & Co. the next year, the book became a success. Now, The Tale of Peter Rabbit is one of the best-selling books to date, and Potter proceeded to write twenty-eight books in her lifetime.

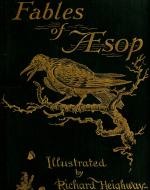

Cover of The Fables of Aesop: Selected, Told Anew and Their History Traced by Joseph Jacobs, The Project Gutenberg eBook, 1992. The tradition of using anthropomorphic animals in children’s literature began with Aesop. In the 4th century BCE, Demetrius of Phalerum compiled Aesop’s short stories, such as "The Tortoise and the Hare," "The Boy Who Cried Wolf," and "The Ant and the Grasshopper.” However, some scholars question whether Aesop was real. Because the name "Aesop" closely resembles "Aethiop," meaning Ethiopian, some scholars speculate these fables may have originated from widespread oral traditions across Africa. No matter the author, the fables anthropomorphized animals to convey moral lessons and symbolize specific traits. For example, the fox represents cunning and the lion represents power. Long afterThe Fables of Aesop, in 1845, Struwwelpeter became the first picture book to feature anthropomorphism in illustrations. Then, in 1865, John Tenniel illustrated the White Rabbit in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a character that later influenced Beatrix Potter’s creation of Peter Rabbit.

Queen Victoria's Favorite Dogs and Parrot by Sir Edwin Landseer, The Victorian Web, 2001. In this image, the artist paints the Queen’s dogs named Dash, Hector, and Nero, and a parrot named Lorey as beautiful and intelligent. Before the Victorian era, the general populace often viewed pet owners as frivolous consumers, expecting animals to work or be eaten. However, during the Victorian period, attitudes toward animals began to shift. The genteel began keeping pets, such as dogs and cats, for their children to serve as playmates, teach them about nature, and offer lessons in kindness. This altered perspective led many authors to personify animals in children’s literature, imagining them as characters to convey the attributes for which they were valued in domestic life.

Beatrix Potter, "Reproductive System of Hygrocybe Coccinea," Wikipedia, 1897. How does Beatrix Potter effectively anthropomorphize animals in her work? Potter--a naturalist artist with an interest in botany, mycology, and entomology--was also a scientist. In the mid-1880s, she began drawing through a microscope, studying fungi and their spores. Eventually, she developed her own theory on how fungi spores reproduce and wrote a paper titled “On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae.” This scientific approach carried over into her children’s book illustrations. In The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Potter demonstrated a deep commitment to present animals as true to nature. Through her realistic illustrations, she captured the physical appearance, personalities, postures, and reactions of her own pet rabbits. The backgrounds in her books were also inspired by the landscapes she visited with her family, further grounding her animal characters in the natural world.

Trio of Images

1. Beatrix Potter, “Mr. McGregor … Intended to Pop [a Sieve] Upon the Top of Peter; But Peter Wriggled Out Just in Time” from The Tale of Peter Rabbit, 1902. In children’s literature, animals are used to simplify complex moral lessons, adhering to the didactic tradition. In this illustration, Peter loses his jacket as he escapes Mr. McGregor. Because Peter disobeys his mother, Mrs. McGregor might have baked him into a pie—the fate of his father. Thus, Peter’s experiences teach children to obey their parents. The story also teaches children that their actions have consequences. However, Potter simplifies the moral lessons of the story by demonstrating them through animal behavior. For example, while Peter’s decision to sneak into Mr. McGregor’s garden to steal vegetables against his mother’s wishes portrays his disobedience, his actions are also instinctual; rabbits are known for being naturally curious creatures. At the same time, his curiosity creates a tension with which children can relate. Further, Mr. McGregor chasing Peter illustrates the consequences of Peter’s actions. A child, however, knows they are safe from such fatal repercussions because they are human; humans hunt animals. Thus, while the story highlights the importance of caution, utilizing animal characters creates a sense of distance between the protagonist and the reader. This distance helps prevent the moral from feeling heavy-handed.

2. Beatrix Potter, "But Peter, Who Was Very Naughty, Ran Straight Away to Mr. McGregor's Garden, and Squeezed Under the Gate!" from The Tale of Peter Rabbit, 1902. Anthropomorphizing animals in children’s literature allows children to relate to the characters. In this picture, Peter squeezes under Mr. McGregor’s gate, demonstrating his childlike mischievousness as he disobeys his mother. This loveable protagonist engages children with his tale because he embodies traits with which they can relate. Without reading the book, someone might think that because he is a rabbit, he acts unintelligent and animalistic. However, readers know the story presents human behavior in the rabbits, such as walking upon their hind legs, wearing clothes, and sharing a common language. Peter even surpasses the average knowledge of an anthropomorphic rabbit in this world; he showcases his cleverness when he outsmarts Mr. McGregor. Further, Peter’s personality reflects the human curiosity and mischievousness of childhood, which often leads to trouble. Peter disobeys his mother and sneaks into Mr. McGregor's garden, tempted by the promise of vegetables. This imperfection makes him relatable. Last, because Peter experiences human emotions, such as excitement and fear, readers empathize with his journey. Children see their own feelings mirrored in Peter throughout the adventure, which fosters their connection to the story. Overall, anthropomorphizing animals is effective in children’s literature because young readers don’t see animals as “other.” They already believe the animals possess human characteristics.

3. Beatrix Potter, “‘Now Run Along, And Don’t Get Into Mischief’” from The Tale of Peter Rabbit, 1902. So why must the animals be anthropomorphic? Not only including animals but also making them anthropomorphic is important in children’s literature because they inspire imagination in children. This illustration depicts Mrs. Rabbit buttoning Peter’s blue jacket before going to the baker’s shop to buy bread and buns. The fantastical elements of the story, namely the anthropomorphic rabbits, inspire imagination in young readers. This is because anthropomorphic animals combine the familiar and extraordinary; children see rabbits in their everyday lives, but in this story, the rabbits are given human characteristics. They can talk amongst each other, wear little blue jackets, and shop for brown bread and currant buns. They drink tea, and their mothers worry over them when they’re unwell. The whimsical nature of this story encourages young readers to explore their own “what-if?” scenarios and create their own stories. Thus, fantasy stories using anthropomorphic animals, such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit, inspire creativity in children.

Collage of Children's Books, Wikipedia. Today, the profound influence of anthropomorphization in The Tale of Peter Rabbit on children’s literature is still apparent. Potter solidified animal stories in children's literature by influencing generations of authors and illustrators, such as A.A. Milne, author of Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), E. B. White, author of Charlotte's Web (1952), and Arnold Lobel, author of the Frog and Toad series (1970s). Peter Rabbit is also the oldest licensed character in children’s literature, and Potter's books have sold over 40 million copies worldwide. Therefore, Peter Rabbit will forever endure as a beloved animal character of our childhood.

Copyright:

Associated Place(s)

Featured in Exhibit:

Artist:

- Beatrix Potter