The Victorian era was host to an array of cultural shifts in literacy and publishing. As printing presses were standardized, books became cheaper and easier to create and distribute to the masses. Mandatory schooling rose as Victorian society began to value education more highly. George Eliot’s wrote her 1860 novel The Mill on the Floss at the peak of these developments, and protagonist Maggie Tulliver interacts with literature and longs for an education. Eliot represents Maggie’s passion for literature as incongruent with Victorian gender roles— she is constantly dissuaded from reading, and pushed towards activities deemed “better suited” for young women. Nonetheless, Maggie attempts to find herself in literature and seeks out a novel that she can feel represented in. While her efforts ultimately come to no avail, Maggie’s interactions with books shape her identity and the narrative at large.

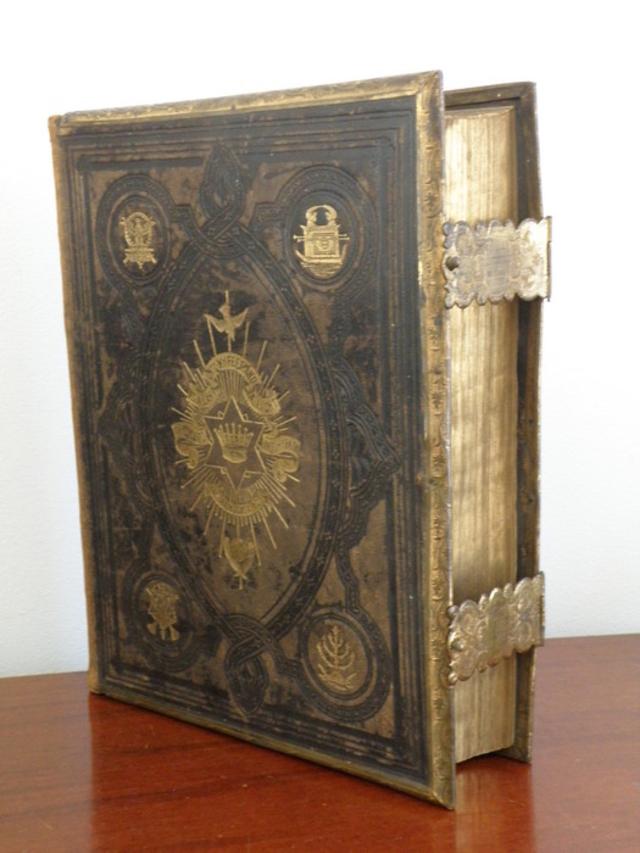

Rev. John Brown Family Bible, Late 19th Century

The Victorian family bible’s significance transcended beyond Christianity. It offered households an opportunity to designate their socioeconomic status, and emphasized the importance of family legacy and honor. This 19th- century Rev. John Brown Bible is fitted with decorative gilt and leather bindings and includes many full-page engravings. This ornate Bible likely belonged to a wealthy family, or was purchased as the aspirational token of a middle-class family such as the Tullivers. In The Mill on the Floss, Mr. Tulliver has Tom sign the family Bible in agreement that he “wish evil may befall” John Wakem, despite Maggie’s protests that “it’s wicked to curse and bear malice” (Oxford 232). Later in Book 5, Tom forces Maggie to swear on the Bible that she will discontinue relations with Philip Wakem. These two instances work in tandem, illustrating that Maggie’s interactions with the family Bible are determined by her father and brother and weaponized against her.

Illustration by G.M. Brighty, “Ducking a Witch” for Daniel Defoe, The History of the Devil, 1819.

Appearing in early nineteenth-century editions of Defoe’s novel, this engraving and accompanying tale make an impression on young Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on The Floss. After she excitedly recounts the scene in Book 1 Chapter 3, Mr. Riley instructs Maggie that The History of the Devil is “not quite the right book for a little girl” and advises her to “read some prettier book” such as Pilgrim’s Progress. Eliot’s novel concludes with Maggie ousted on false accusations of adultery and drowning to her death — an ironically similar fate to the supposed witch she defends in Book 1. The History of the Devil is the first of three books that Maggie reads in an endeavor to place herself in a gendered society that opposes her rambunctiousness, curiosity, and love of literature. Her favorable reading of the witch foreshadows her own demise.

Illustration from The Christian Pattern, or the Imitation of Jesus Christ, Thomas à Kempis, London, 1710

This image from Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ and precedes the first book entitled “The Sighs of a Penitent Soul: Or, A Treatise of True Compunction.” The illustration’s Latin inscription can roughly be translated to “Oh slippery darkness, how long will I be involved with you?” The woman pictured (likely Eve) clutches her heart as she kneels amongst a skull, snake and sword — items portraying the temptation from which “darkness” is born. Thomas à Kempis casts temptation as being completely antithetical to Christian devotion, yet bows to the traditional reading that Eve (and therefore all women) are the ultimate holders of desire and temptation. This paradigm leaves little room for Eliot and Maggie to acquiesce in Christian devotionalism, as their femininity is cast as sinful. George Eliot and Maggie conceivably viewed this exact illustration, sourced from a London 1710 edition of the book.

Elizabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun, Madame de Stael as Corinne at Cape Miseno, Switzerland, 1807-9

In this 1808 portrait, Madame de Staël poses as Corinne, the titular protagonist of her 1807 novel. Dually a painting of author and character, this “muse portrait” captures da Stael’s self-insertion as crucial to Corinne. Similarly, many events from The Mill on the Floss were appropriated from Eliot’s own life. When Philip lends Maggie a copy of Corinne, she refuses to finish reading out of frustration that “[the] light-complexioned girl would win away all the love from Corinne and make her miserable” (292) Out of all that Maggie reads, Corinne ironically would have offered her the most insight. Corrine similarly values reading and independence, and struggles with conforming to European gender roles. However, Maggie projects her own insecurities onto the novel and shies away from the resemblance. Madame de Staël and George Eliot both write sympathetic semi-autobiographical characters who are unable to overcome gender-based adversity in the same way they themselves did in real life.