Created by Catherine Golden on Wed, 08/24/2022 - 18:46

Description:

At the opening of Jane Eyre, we find Jane reading A History of British Birds (1797, 1804) by Thomas Bewick. The natural history book captivates and comforts young Jane, who lives unhappily with the Reeds at Gateshead. Reading Bewick in secret in the window seat, Jane returns us to a source that influenced the life of Charlotte Brontë and her siblings. The Brontë family owned an 1804 edition of Bewick's A History of British Birds. This two-volume nonfiction work inspired the early artwork of Charlotte and her siblings, all of whom imitated Bewick's drawings: Branwell, the snapping farmyard dog; Charlotte, a cormorant (water bird) on a stormy sea; Anne and Emily, bird studies, including Emily's vignette of a peasant herding geese. In 1832 upon Bewick's death, Charlotte wrote a poetic eulogy to the great artist. Those who read Jane Eyre and A History of British Birds side by side discover descriptions of Bewick's pictures of desolate ships, phantoms, thieves, ghastly moons, and a solitary graveyard that closely match the woodcuts (approximately 2" by 3") positioned as tailpieces to Bewick's chapters on various water birds. The Bewick images are small black-and-white woodcuts, but they loom large in our imaginations, suggesting that Jane, in describing them, also recreates them. A History of British Birds also makes a cameo appearance in Anne's The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848).

Thomas Bewick, A History of British Birds, in two volumes, 1797, 1804, British Library. A History of British Birds is a two-volume natural history that combines detailed history and precise drawings. Volume 1, Land Birds, came out in 1797 while Volume 2, Water Birds, was published in 1804. Ralph Beilby wrote the text for the first volume, but Bewick wrote the text himself for the second volume. The book, a quintessential field guide for the non-specialist, has earned acclaim both for the beauty and clarity of Bewick's wood-engravings, which are still considered his finest work.

James Ramsey, Portrait of Thomas Bewick, n.d., Wikipedia. Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) was a celebrity in his own time. He is credited for innovating a technique for wood engraving that resulted in high quality drawings. His speciality was tailpieces, small woodcuts placed at the end of a chapter to fill in gaps since each entry in a natural history started on a new page. Bewick gained fame for his illustrations to Aesop's Fables published in 1784 and A General History of Quadropeds published in 1790. But his greatest achievement remains A History of British Birds, a work that is also readily associated with the Brontës. The Ramsey portrait emphasizes the seriousness and stature of the "mighty artist," as Charlotte refers to him in "Lines on the Celebrated Bewick."

Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, 1846, ABE Books. Bewick received poetical tributes during his lifetime and after his death. In 1798, William Wordsworth praised Bewick in his poem "Two Thieves" with the line "O now that the genius of Bewick were mine"--an admission that if he were skilled as an artist, he would stop writing! Alfred Lord Tennyson and Charlotte Brontë also penned poems of tribute after the artist's death. In 1832, Charlotte wrote "Lines on the Celebrated Bewick," composed of 20 quatrains. The opening four quatrains read as follows:

The cloud of recent death is past away,

But yet a shadow lingers o'er his tomb

To tell that the pale standard of decay

Is reared triumphant o'er life's sullied bloom.

But now the eye undimmed by tears may gaze

On the fair lines his gifted pencil drew,

The tongue unfalt'ring speaks its med of praise

When we behold those scenes to nature true-

True to the common Nature that we see

In England's sunny fields, her hills, and vales,

On the wild bosom of her storm-dark sea

Still heaving to the wind that o'er it wails.

How many winged inhabitants of air,

How many plume-clad floaters of the deep,

The mighty artist drew in forms as fair

As those that now the skies and waters sweep !

These lines convey not only Charlotte's deep sorrow at the death of the "mighty artist" but also her great admiration for Bewick's ability to draw "scenes to nature true."

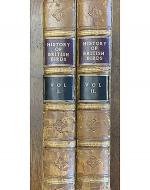

Thomas Bewick, "The Golden Eagle," History of British Birds, 1797, 1804, British Library. This full page engraving of the Golden eagle, the "largest of the genus," reveals Bewick's supreme skill in drawing birds "to nature true." Bewick captures the distinctive foot and talons of this bird of prey as well as its ridged beak, small head in comparison to its large body, and its intricate plumage.

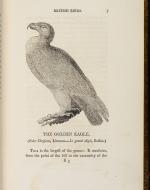

Fritz Eichenberg, "Jane Reading in the Window Seat," Jane Eyre (1847), 1943 Random House edition, personal collection. At the opening of the novel, Jane describes her experience reading "Bewick’s History of British Birds: the letterpress thereof I cared little for, generally speaking; and yet there were certain introductory pages that, child as I was, I could not pass quite as a blank. They were those which treat of the haunts of sea-fowl; of 'the solitary rocks and promontories' by them only inhabited; of the coast of Norway, studded with isles from its southern extremity, the Lindeness, or Naze, to the North Cape—.” Eichenberg changes Jane's posture--she is not mounted "like a Turk" as Charlotte poses her in the book--and the curtains remain open. However, Eichenberg expertly captures Jane "reading" the Bewick illustrations so intently in her private reading nook, that is until she is disturbed by her cousin John Reed, who flings the Bewick book at her and tells her not to rummage his bookshelves.

Thomas Bewick, Tailpiece to "Razor-Bill," for A History of British Birds, Volume 2, 1804, personal collection. Bewick created many attractive images of birds in their natural surroundings, but Jane ferrets out vignettes akin to the wild, at times desolate, landscape of the moors. "Each picture told a story;"---Jane tells us--"mysterious often to my undeveloped understanding and imperfect feelings, yet ever profoundly interesting: as interesting as the tales Bessie sometimes narrated on winter evenings, when she chanced to be in good humour." Seemingly overlooking beautiful pastoral images of a peacock and swan or the majesticness of a Golden eagle pictured in this case, Jane lingers over pictorial moments that speak to her sense of isolation while living amongst the Reeds at Gateshead. The vein of popular culture that Bewick presents in vignettes with foul and turbid weather, supernaturalism, death, and violence fascinates Jane. The graveyard image that sparks Jane's fancy is easily identifiable. The words on the "inscribed headstone" read forebodingly, "Good Times & Bad Times & all Times get over." The tombstone casts a long and dark shadow, and the "newly-risen crescent" throws an eerie light on the solitary trees, broken wall, gate, and tombstone. Jane states, "I cannot tell what sentiment haunted the quite solitary churchyard," but to the reader-viewer, the scene exudes a weird air.

Thomas Bewick, Tailpiece to "Black-Throated Diver," A History of British Birds, Vol. 2, Personal Collection. Jane is haunted by another easily identifiable Bewick image: a fiend pinning down a man through his pack. Again, the picture has not connection to the text describing the black-throated diver. The piercing expression and sharp antennae-like horns of the winged fiend likely make this illustration an "object of terror" to Jane. Thefiend has a menacing arrow-shaped tail. The sharp spear restrains the man whom Jane interprets to be a thief. The lumpy shape of the pack on the "thief's" back suggests it contains a body, presumably a dead one. To compound the terror, the thief seems unaware of the menace behind him. Not being aware of a horror behind one's back likely made this image disturbing to Jane Eyre, forever unsure of her next encounter with an unsympathetic servant, a cruel aunt, or a menacing cousin.

Valentina Catto, cover to The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) by Anne Bronte, Folio Society edition, 2020. In the final chapter of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall when Gilbert reunites with Helen, Bewick makes an appearance. Helen sends little Arthur off "under pretence of wishing him to fetch his last new book to show" Gilbert (Bronte 482). Just after the couple declare their mutual love, Arthur eturns with the book: "Look, Mr. Markham," he cries, "a natural history with all kinds of birds and beasts in it, and the reading as nice as the pictures!" Although the text is not named, it is Bewick's A History of British Birds. Arthur's enjoyment of the text and the pictures offers a twist on young Jane Eyre's preference for the pictures only. Moreover, Bewick is not read in solitude in Tenant. "In great good humour, I sat down to examine the book and drew the little fellow between my knees," notes Gilbert; and young Arthur Huntingdon and Gilbert Markham read Bewick's renowned work of natural history together.