In this edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the illustration accompanying stanza XLVI, along with the unique addition of the illustrator’s own contextual information of the illustration, seems to evoke more of a condemnation of religious belief in afterlife than the stanza alone communicates (see fig. 0-1). In this way, although the illustration artistically deviates from a more literal sense of the stanza in favor of an individual interpretation from the illustrator, it works to emphasize a theme present in the text as a whole rather than a isolated reading—a feature that is especially interesting given the physical placement of the illustration and stanza within this edition. This edition of Rubáiyát has the unique feature of including more involved illustrations of select stanzas, being placed at the end of the edition after an illustrative rendering of the full poem—it thus exists in the edition as a sort of “highlights reel.” Whether these selected stanzas were thought to be emblematic of the text as a whole, or simply chosen as a result of the illustrator’s preference is unclear. And yet, regardless of the intention, these stanzas exist apart from the whole of the edition, removed from their context, and almost inviting a close-reading.

Stanza XLVI depicts humans as “Phantom Figures,” moving around the sun for no purpose other than to be a passive participant in a "Magic Shadow-Show.” This stanza plays into an existing theme of religious skepticism as it begins with the statement that beyond this “Show,” there exists nothing “in & out, above, about below,” applying a rejection of the physical realms of a heaven or a hell/an afterlife in general. In characterizing humans as simply “Phantom Figures,” the stanza implies that we occupy no material substance on earth as we often think or are told that we do—it instead implies that we are merely passive and ephemeral beings with no grand life meaning other than to occupy a short role in a “show/Play’d in a Box.” This “Phantom” characterization also serves to continue the line of thought of the rejection of an afterlife—in its insistence that we are not active beings, it is also implied that we cannot have material impact, such as the production of sin that would presumably lead to an afterlife.

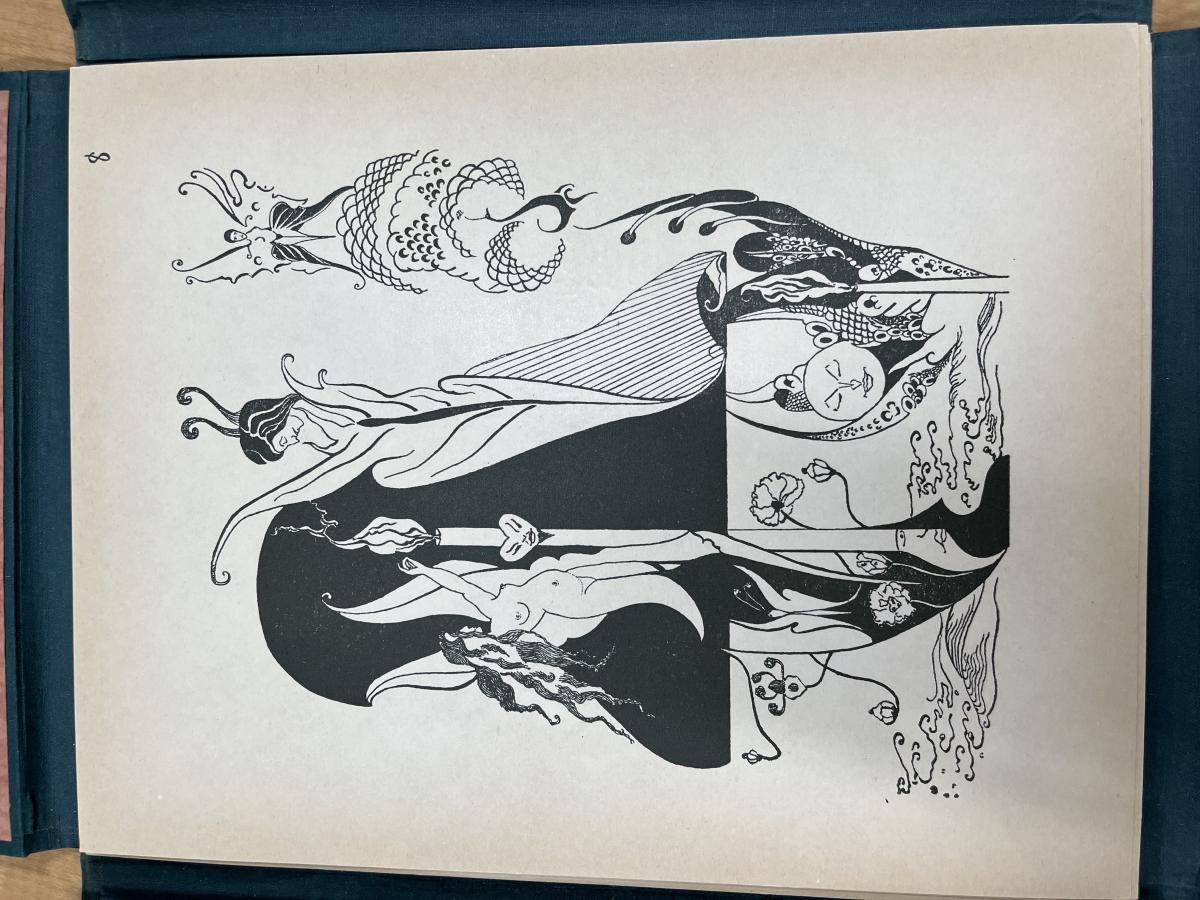

While the stanza alone presents a clear skepticism and even full rejection of religious thought, the illustration takes a more abstract, highly artistic approach in its depiction. The most notable differences between the illustration and the stanza is how the human figures in the illustration are not depicted as the literal “Phantom Figures” of the poem, but instead as winged creatures, which the illustrator explains in the Introduction, are supposed to be moths. These moths, instead of going around the candle-sun, seem to be reaching for the candle, naturally drawn in by its light. As previously mentioned, this edition of Rubáiyát is unique in that the front matter includes a note from the illustrator M.K. Sett, which includes a brief passage for each illustration, often explaining particular elements, or recounting the source of inspiration behind certain designs. The caption for the chosen illustration reads: “Eternity is a never-ending flame; and beings, the moths that court it. A tripping measure, a valse, a dirge, and then, finish—like the flowers that give us joy of life, the waves whose talk is like the murmur of the beloved, and the beautiful moon; to die! (How soon the beautiful dies!)” (see fig. 2, desc. for picture 8). In this, the illustrator seems to ignore the poem’s literal sense of the candle as a sun in favor of an interpretation of the candle around which humans travel as the allure of eternity, and thus the allure of the promises of religion and the existence of an afterlife. While the stanza alone presents its religious skepticism through the idea that we are passive “Phantom” creatures playing a role in a show, the illustration insists with more clarity that humans are actively being tricked to believe in eternity, as they are involuntarily lured to the candle of eternity as moth creatures. This depiction works to incorporate more themes present in the text as a whole, as humanity is later related to “Pieces” in a “Chequer-board of Nights and Days” being moved with no purpose (LIII).

Works Cited

Khayyám, Omar. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Translated by Edward Fitzgerald, illustrated by M.K. Sett, D.B Taraporevala Sons & Co., circa 1946.