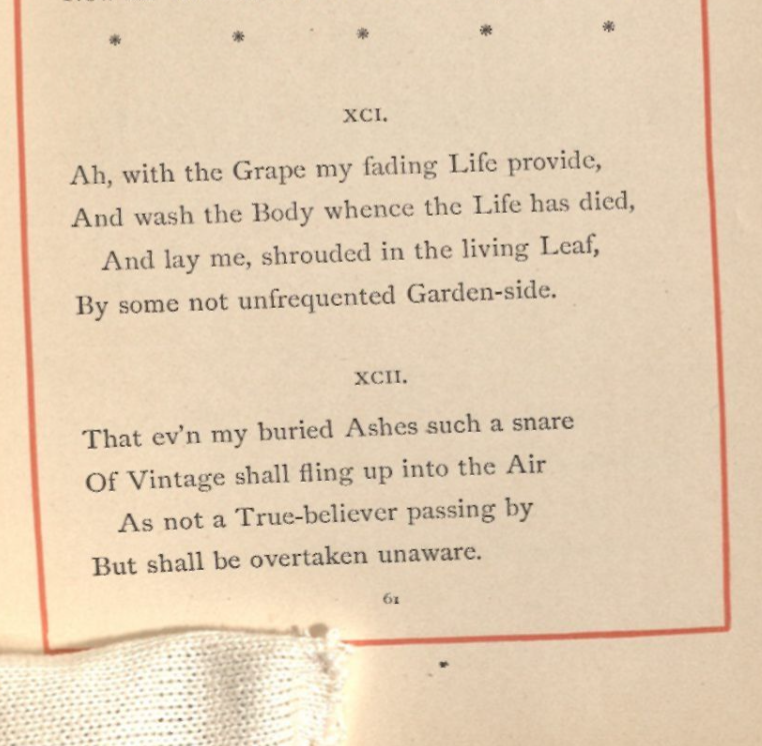

While many editions of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám utilize detailed images and ornamental page borders to paint a scene to the readers, often times versions of the poem relied on the readers’ imagination alone to provide a sense of peace and pleasure, even in the face of its more somber subjects such as death. As an affordable option for lower-class readers, Houghton, Mifflin & Co.’s 14th edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: The Astronomer-Poet of Persia lacks the ornamental adornments that many other editions proudly display so the emphasis,, stays on the text itself, the stanzas remain unaccompanied and left to deliver any poetic intentions to the reader by their imagery alone. Thankfully, the Rubáiyát is rife with descriptive poetry and each version of Edward FitzGerald’s English translation, even with their small tweaks, still preserves Omar Khayyám’s adoration for poetry that incites pleasure in its readers. While this edition uses FitzGerald’s 4th edition from 1879 which has cut nine stanzas due to Fitzgerald’s desire to have only 101 stanzas (87) , it stills retains many of its more descriptive verses, such as its stanza XCI:

“Ah, with the Grape my fading Life provide,

And wash the Body which Life has died,

And lay me, shrouded in the living Leaf,

By some not unfrequented Garden-side.”

Since the Rubáiyát’s speaker spent many previous stanzas discussing a life spent in pleasure, notably with wine, his last wish to be turned into wine seems fitting, his life returning back to what has nourished it so far. While the Rubáiyát expresses religious skepticism of a life after death, it does offer the reader an idea of peace for death, that one’s body will offer a new life through nourishing plants in a garden “not unfrequented” by others who will get to experience its beauty. The stanza retains a light, even joyous tone as its one line mentioning death explicitly is immediately followed by explicit life of “the living leaf.” The speaker proposes a peaceful, serene idea of death to the readers, the “fading” body beginning to return to nature before its final death as the speaker’s blood turns to wine itself: the “Grape” of his body washing away the death, or decomposition, of the speaker’s corpse. This idea of natural burial is composed as a final wish, instructing the reader to “lay” the speaker wrapped in live nature in a beautiful place, thereby making his own death beautiful by association.

Interestingly, the 4th translationedition’s version of this stanza is altered from FitzGerald’s 1st translation, mainly in its descriptions of the shroud the speaker wishes to be wrapped in, but also in regards to who is receiving the funeral rites. FitzGerald’s 1st edition of this stanza (numbered LXVII) originally has the second line refer directly to the speaker: “And wash my Body whence the Life has died,” (49) whereas the 4th translation refers to the corpse in abstract, “And wash the Body which Life has died.” While the changes are slight, it impacts the message of the line: the 1st edition having the speaker still retain possession of his corpse and “the Life” purporting as a state of being that has cease while the 4th edition removes any personal possession of “the Body” and “Life” possibly acting as a more personified concept. These changes result in the 4th edition of translation being far more abstract and spiritual, separating the speaker from the corpse of his body entirely and engaging with Life as an entity rather than a state of being. The image remains vivid, but the details differ just slightly enough for the readers to interpret death as something that happens to their body, not to themselves.

Khayyam, Omar, et al. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Oxford University Press, 2010.