Created by Molly Jordan on Thu, 10/20/2022 - 14:16

Description:

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë were introduced to art in the same way that many other Victorian middle-class women were--through the reproduction of prints that were published and made by male artists. Even members of the growing middle class could afford one or two sketches or a popular gift book, including intricate portraits, landscapes, and images with Biblical and literary themes. This igrowing emphasis on "accomplishments" for middle-class women made drawings along with embroidery and singing mandatory for girls seeking to advance in their schooling and attain upward mobility and employment. Women discouraged from becoming creative artists but rather to make artwork as a beneficial use of their recreational time to decorate their homes or to teach. Girls and young women including the Brontës and, in turn, their fictional characters learned by mimicking the increasingly popular commercial prints until they could replicate them properly.

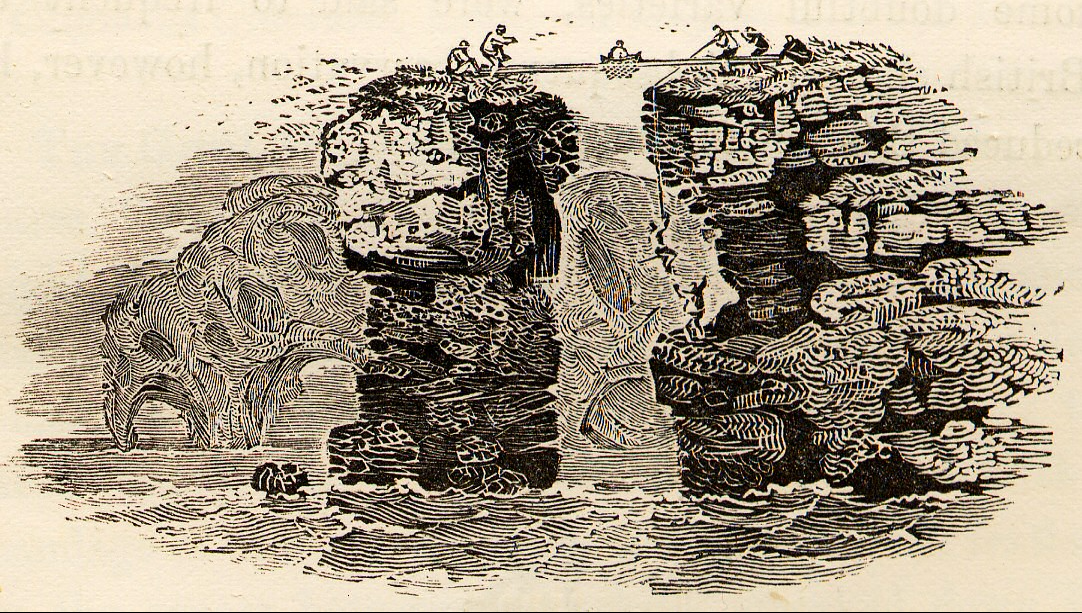

Thomas Bewick, tailpiece, History of British Birds, 1804, Wikipedia. The piece has no caption, but the image is of people trying to retrieve birds' eggs from a nest between two sea cliffs. For this volume, Bewick chose a seabird theme. Bewick's two volumes appear in Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre, giving Jane an imaginary escape from her abusive cousins and aunt at Gateshead. Although the narrative and imagery take Jane to amazing realms, their unsettling paranormal components terrify her and foreshadow future experiences with the otherworldly. Jane is particularly captivated by Bewick's tail-pieces, which is why I recreated one of his tail-pieces.

Molly Jordan, duplication of Thomas Bewick's 1804 tailpiece from The History of British Birds, uncaptioned, 2022. This is my recreation of the above tail-piece in Volume Two of Water Birds by Thomas Bewick. I, like the Brontës, chose a print that was already published and duplicated it. When creating the image, I did not only find it difficult, but I sometimes found myself bored and wanting to make the process more creative instead of simply copying. This is what I can only imagine other girls and young women also experienced when doing the same sorts of exercise to cultivate their skills. I find it telling that only through these types of accomplishments, which lack creativity, could middle-class women appear more talented and suitable for marriage or a position such as a teacher or a governess. Women were not supposed to succeed outside of those areas, yet the Brontës were accomplished artists and writers. Like many women of the time, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë learned how to sing, draw, paint, write novels and poetry, sew, and do needlepoint, showing their brilliance as women of many talents. Although Victorian middle-class women were not encouraged to be creative, they were masters at many different skills, which allowed them to pursue their creativity.

Branwell Brontë, "Pillar Portrait," 1834, National Portrait Gallery. The third image is the sole surviving group image of the three Brontë sisters. It is known as the 'Pillar portrait' because Branwell took his own likeness out of the painting before he finished it. His shape lurks behind the pillar between Charlotte and Emily. Despite the fact that the painting is incomplete, the portraits' resemblances to the sisters were judged to be good. The artwork remained at Haworth Parsonage until Rev Patrick Bronte's death in 1861.

Charlotte Brontë, Portrait of Anne Brontë, 1834, Brontë Parsonage Museum. Anne Brontë is the most sketched and painted member of the Brontë family. This painting is one of Charlotte's three portraits of Anne. 'Portrait of Anne Bronte, by her Sister, Charlotte Brontë, June 17th, 1834' is handwritten on the back, and this would have been painted while Charlotte was studying painting, most likely to become a muralist. It has been shaped into an oval and placed on a background, implying that it was formerly hung on the walls of the Parsonage, where it now hangs in the museum. To view the entire picture, please click here.

From the confirmed images of Anne, we discern she had an oval face and a Roman nose. Many of the drawings, particularly the portraits done by the Brontës, have been misidentified or wrongfully identified as one of the other three sisters. While the three of them were still living, photography was expensive and inaccessible in their remote parsonage, so all of the most reliable sources of what the sisters looked like come from portraits and sketches of them. Sketches and portraits are not as reliable as photos, so it’s very easy to have an inaccurate or idealized image of an individual. Though there are confirmed visages of the sisters that exist, much debate has spread all the way back to when the sisters were alive as to whether or not any of these are entirely accurate. The Richmond portrait of Charlotte has been claimed to be a more idealized version of what she looked like, which under-emphasized her larger forehead and nose, making the image resemble Anne and Charlotte. Because there are confirmed portraits of the Brontës, historians do have a general idea of what they look like, but there aren’t any definitive look-alikes.

Charlotte Brontë, Portrait of Anne Brontë, 1845, Wikipedia. Despite that the figure was not identified as Anne at the time, the sketch was the frontispiece for the 1905 and 1907 editions of Tenant of Wildfell Hall with the caption: "Brontë, Anna Charlotte Bronte's pencil sketch." The features, however, differ from those shown in Anne's two previous portraits. In all of the images, her bottom lip extends over her chin, and her top lip extends even more. These features seem to be more idealized, but the portrait is still seen as accurate. This is the second of Charlotte's portraits of Anne, and because Charlotte Brontë was the sister who lived the longest, we have the most work from her. There have been 180 original confirmed drawings by Charlotte. For Charlotte, drawing and painting were more than an 'accomplishment'; it was prospective employment and a method to avoid the other two accessible occupations for an unmarried woman her age, which were a teacher in a school or a private governess. She carefully copied prints until she became an adept amateur, even presenting two drawings at Leeds in 1834, hoping to acquire the skills to become a professional miniature painter. Even still, she seldom drew from reality or her imagination. Here's an example of Charlotte Brontë's replicated drawing of Thomas Allom's etching of Derwent Water in the Lake District. During the 1830s, Allom published a number of volumes of scenic engravings, and Charlotte is said to have created a number of drawings based on his work. This one is well known among Brontë historians but went missing in the twentieth century.

Branwell Brontë, "Profile Portrait," 1833, Wikipedia. Though the identity of this portrait is uncertain, it is believed to be of Anne or Emily. Branwell Bronte produced two group paintings of his siblings in the 1830s: the 'Pillar' portrait wherein Branwell's visage is obscured behind a pillar, and the 'Gun' group in which Branwell is carrying a gun. This profile is thought to have been removed by Arthur Bell Nicholls' rom the 'Gun' group portrait following the death of Rev Patrick Bronte in 1861 and carried to Ireland with him. It was discovered and bought by the National Portrait Gallery in 1914.

(None of the below are in the public domain, but they are all important and interesting works of, and by the Brontës)

Charlotte Brontë, "Portrait of a Young Woman," Artnet. Charlotte's 'Portrait of a Young Woman,' which dates from the 1830s or early 1840s but cannot be precisely dated. It might have been part of Martha Brown's Bronteana Collection. It is now known that it was afterward held by historian, and Brontë fan, Joseph Horsfall Turner. Charlotte is the only member of the Brontë family who resembles her pencil picture. She HAS huge eyes with a notable lower eyelid drop, high cheekbones, broad cheeks, a prominent chin, and a low jaw. Charlotte Brontë's eyes were the most commented-upon feature throughout her lifetime. If the drawing is a self-portrait, it might have been made using two mirrors, previous portraits, or a transfer with an idealized nose and brow. Charlotte was interested by physiognomy, assessing individuals based on facial traits; this fascination pervaded her writings, but it is speculated that she was self-conscious about her own looks.

Charlotte Brontë, "Portrait of an Unidentified Woman," British Library. This self-portrait may not be an exact likeness, but it does include some identifying features. Charlotte Brontë made a pencil sketch of another unidentified woman; although no identity is linked to it, it might represent a fictional character from her fantasy country of Angria. The picture demonstrates Brontë's developing creative abilities as a teenager, with its carefully regulated shade and fine line work.

Anne Brontë, "Portrait of a Young Woman," The Brontë Sisters, UK.

Anne Brontë, "Portrait of a Young Woman in Blue," The Brontë Sisters, UK. Anne Brontë painted portraits of two unnamed young women. Both were done in the early 1840s of women who had large eyes and curls. It has been hypothesized that one, or both, of these might be self-portraits of Anne Bronte at various points over the 1840s when Anne would have been in her 20's. Though not as developed as an artist as her sister, Anne through the existence of these portraits illuminates the Brontë sisters were women of many talents other than writing. Both images can be found here, the second to last set of images.