This is a gift-book edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, by Edward Fitzgerald. This book uses the fourth edition of Fitzgerald's translation of the Rubáiyát. It was published by R.F. Fenno & Company sometime in the 1880s out of New York City. The book's title page features the publisher's address.

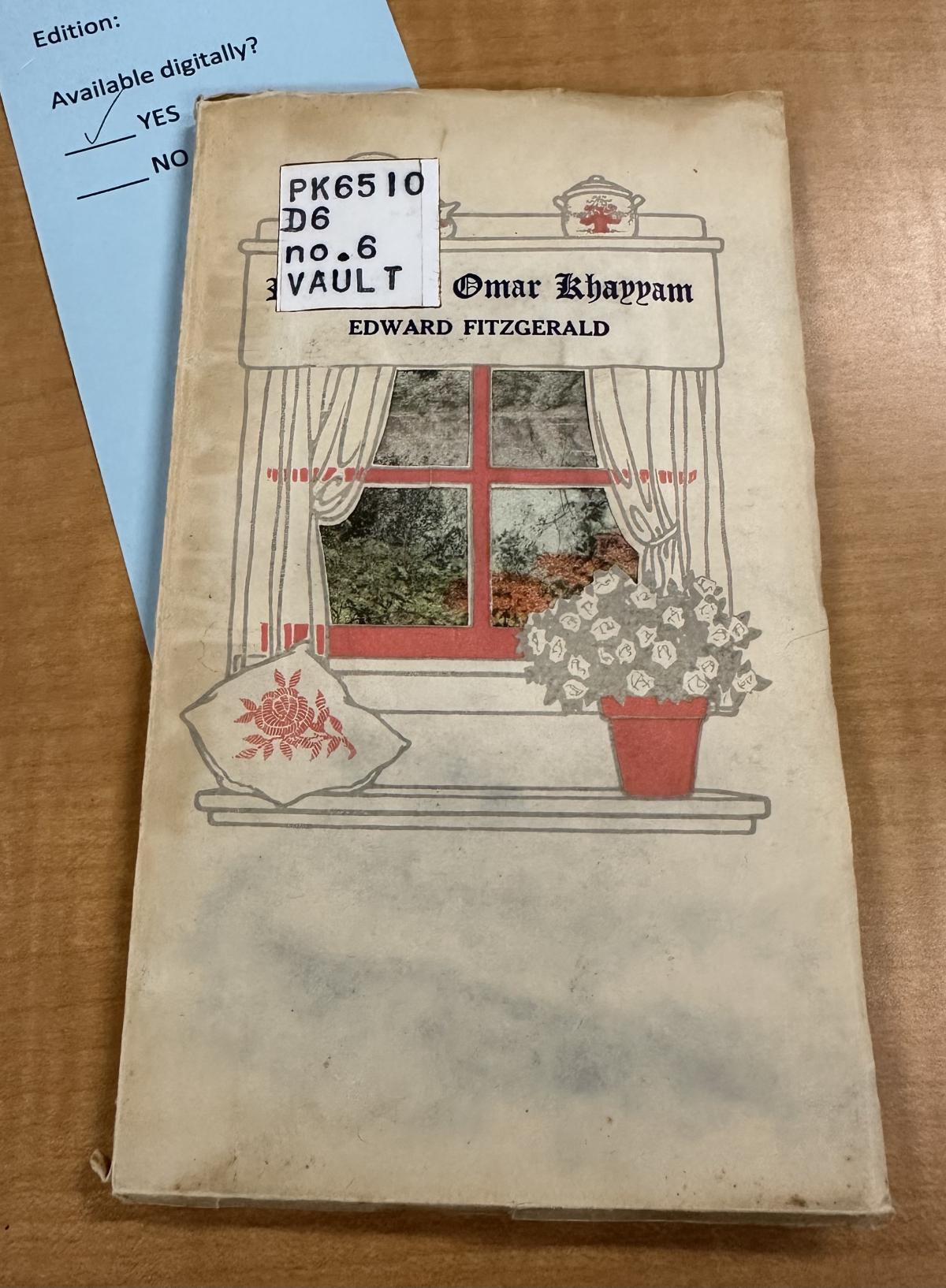

The actual cover of the book (see image 1) is a strange texture. It is done in an embossed paper that has aged over its lifetime, and it feels odd compared to typical paper or cloth bindings. The cover features an illustration of a home-scene, with a pillow, some pots, a potted rose plant, and a window. The window features a scene behind it, with the actual panel and curtains being raised from the illustration behind it. The illustration of the outside appears to be of a bush and blue sky, but the style and likely the aging of the paper make it difficult to discern. This indicates it was likely a mid-point in terms of price gift-book.

The book features a few illustrations in the front and end matter (see image 2). They are black-and-white line work that portray decorated shelves that feature candles, plates, books, and crawling ivy. They appear to be done with a printing press block as a couple of illustrations appear several times. There is no illustrator name, which leads me to believe these were just blocks owned by the publisher and was likely used in several different publications.

This edition of the Rubáiyát features several introductory material about the poem, including bibliographical descriptions of both Omar Khayyám and Edward Fitzgerald. This version has 117 pages, not including the frontmatter and decorative blank pages at the front and back. The actual poem begins at the very end of the book, and the print quality of the poem is noticeably messier and less clean than the beginning sections.

The book features an inscription on the first page (see image 3), which is set on a striped paper with one of the shelf illustrations. The inscription reads: “Merry Christmas, To Dorothy From Barbara,” in a big, cursive script. It appears the inscription was written with a pen and is faded. This could indicate that the inscription was written around the time the book was bought originally. Or, it could be this was regifted a number of years after and was written with a weak pen. There is no date on the inscription, or indication of the relationship between Dorothy and Barbara.