For Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), play represented the “independent outward expression of inward action and life” (29). In Maria Dinah Craik’s The Little Lame Prince and His Traveling Cloak (1874), play and toys are consistently used to contextualize Prince Dolor’s maturation, while also providing insight into Dolor’s expanding view of himself and the world around him. In this way, toys and playing function in Craik’s Little Lame Prince in the same way as Froebel’s Play Gifts.

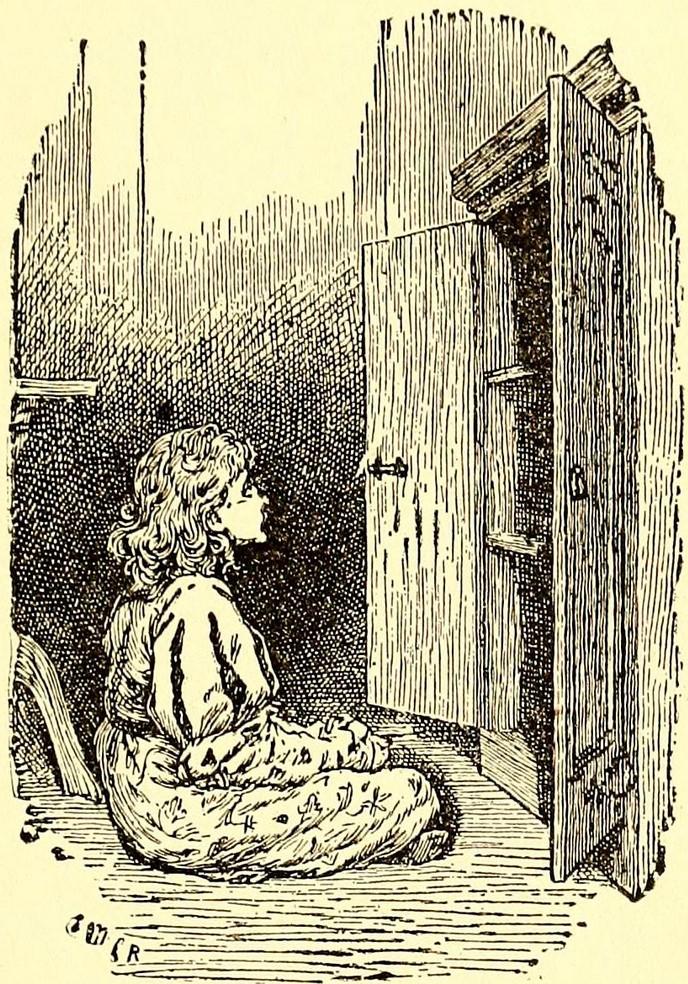

Dolor’s most cherished toys are “his beloved headless horse, broken cars, sheep without feet, and birds without wings” (Craik), which in their physical appearance reflect deficiencies of mobility. Froebel insists that “objects not yet seen in life by the child may be introduced to him through word and playthings that represent these objects” (49-50). For Dolor, who in his isolation has not yet seen horses, cars, sheep, or birds outside of the books he reads, toys allow him to learn about these objects and animals of the world. The physical and mobility deficiencies in Dolor’s toys connect these unknown objects directly to himself and his lived experiences, which promotes Dolor’s self-development. Froebel insists that “man seeks even as a child to develop himself as well everything in Nature by means of that which is opposite yet resembles it” (32). Dolor’s toys facilitate Dolor’s ability to see animals and objects that represent freedom (the opposite of his isolation), while their mobility deficiencies supply the resemblance Froebel discusses.

In the context of disabilities studies, the definition of representation extends beyond “and image that stands in for and points toward a thing” (Bérubé 151), to include a recognition of who and what is “empowered to stand in for and express the wishes of another group” (Bérubé 151). As beloved and cherished toys, Dolor’s “broken” toys retain their value, even when their usefulness as toys is set aside. In this way, Dolor’s toys also represent his own value and innate usefulness, despite a perceived diminishment of mobility.

When Dolor outgrows the toys within his environment, his godmother (Stuff-and-Nonsense) arrives with new toys that incorporate multiple senses. Like Froebel’s “Play Gifts”, Dolor’s godmother provides him with a series of gifts that encourage his exploration, experimentation, and mobility. Dolor receives a traveling cloak to support his freedom of movement and exploration of the world beyond his tower, a pair of golden spectacles that allow him to see in the distance, and a pair of silver ears that allow him to hear distant sounds. Each of these gifts is designed to heighten and expand Dolor’s inherent skills in much the same way as Froebel’s Play Gifts, and each gift is given sequentially as Dolor requires each enhancement in accordance with his own self-directed activities.

From a young toddler playing with undefined toys in the corner of the room, to a growing boy who is free to experiment, expand, compare, and contrast his own experiences with the world around him, Dolor’s toys facilitate his growth and development. Through his toys, as well as through the Play Gifts given to him by his godmother, Dolor learns about the world beyond his tower, allowing him to grow into a king who fulfills the duties of his rank while gaining the love and respect of his subjects.

Sources:

Bérubé, Michael. “Representation.” Keywords for Disability Studies, 2015, pp. 151-155. JSTOR,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt15nmhws.53.

Craik, Maria Dinah. The Little Lame Prince. COVE Studio, 1874.

Froebel, Friedrich. Pedagogies of the Kindergarten, or His Ideas Concerning the Play and Playthings of the Child. Translated by Josephine Jarvis, New York, D. Appleton and Company, 1895.