Exhibit:

Paget’s Iconic Image of Holmes

Since his first appearance in Strand Magazine over a hundred years ago, Sherlock Holmes has reappeared in countless adaptations spanning across just about every artistic medium. This is to be expected, as detective fiction is one of the most heavily adapted genres in the world, constantly being remade in film and television because of its innate ability to offer commentary on cultural context whilst also providing blockbuster action moments (McGraw 11). Three recent reimaginings of the iconic Holmes character that have taken entirely different routes to offer such commentary are BBC’s Sherlock, CBS’s Elementary, and FOX’s Family Guy episode, “V is for Mystery.” While Sherlock strives to evoke a nationalistic pride in British viewers by maintaining close ties to Sidney Paget’s iconic illustrations of the character, Elementary and Family Guy both challenge Paget’s vision as a way of creating a modernized model of Holmes that is more in keeping with modern American culture.

Since his first appearance in Strand Magazine over a hundred years ago, Sherlock Holmes has reappeared in countless adaptations spanning across just about every artistic medium. This is to be expected, as detective fiction is one of the most heavily adapted genres in the world, constantly being remade in film and television because of its innate ability to offer commentary on cultural context whilst also providing blockbuster action moments (McGraw 11). Three recent reimaginings of the iconic Holmes character that have taken entirely different routes to offer such commentary are BBC’s Sherlock, CBS’s Elementary, and FOX’s Family Guy episode, “V is for Mystery.” While Sherlock strives to evoke a nationalistic pride in British viewers by maintaining close ties to Sidney Paget’s iconic illustrations of the character, Elementary and Family Guy both challenge Paget’s vision as a way of creating a modernized model of Holmes that is more in keeping with modern American culture.

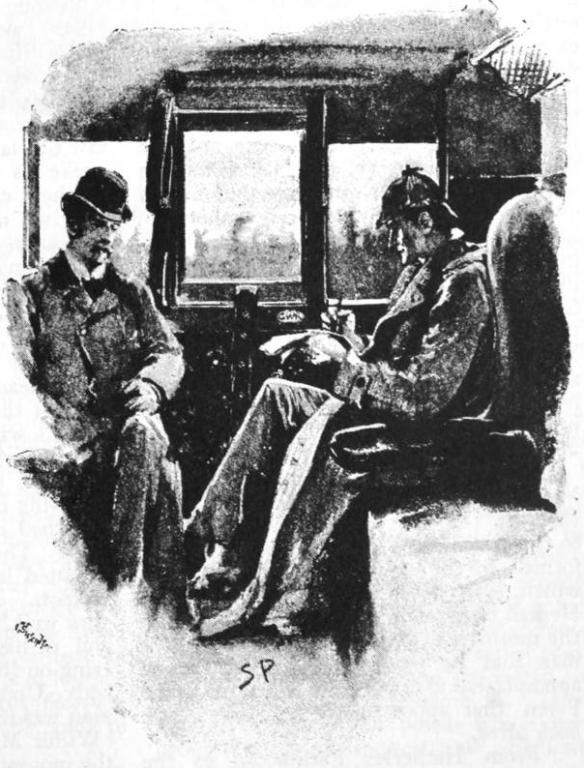

As a frequent collaborator with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sidney Paget worked closely with the writer to create the iconic Holmes image. Paget created more than 350 illustrations of Holmes, contributing greatly to the detective figure’s international popularity (Diniejko). Not only that, the illustrations created by Paget have added to the longevity of the sleuth, with modern adaptations throughout the years being inspired by Paget’s vision for the character. The iconic image of Holmes wearing a long cape and deerstalker hat first appears in Paget’s illustration, “we had the compartment to ourselves” in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” (Figure 1; right). What is most significant about this image is that Doyle himself never refers to Holmes’ outfit as such. Paget alone decides to give Holmes this hat which goes on to become the detective’s most iconic symbol. It is this very image of Holmes as constructed by Paget that all modern adaptations of the sleuth work with, whether to enforce Paget’s vision to the character or to challenge it.

Not a Psychopath, a High-Functioning Sociopath

BBC’s television program Sherlock that began in 2010 offers a contemporary version of Sherlock Holmes in present-day London. Pre-release trailers advertised the show as “a new sleuth for the twenty-first century” (BBC 0:34). However, while the series modernizes the text in some ways (particularly through the modernization of Holmes’ technology) Sherlock clings to many of the original aspects of Holmes’ appearance as a way of celebrating and highlighting one of Britain’s most iconic characters in the midst of a strong rise in British nationalism. British Nationalism did not emerge until after the Second World War, decades after Holmes first appeared in Strand Magazine, and it was not until the 2000s that decolonization efforts across the world brought nationalism to its peak in the country (Ashcroft and Bevir 24, 37-38). However, as one of the most beloved characters in British literature, it is no surprise that the BBC’s modernized version of Holmes still features Paget’s iconic vision of the character so strongly in keeping with this new rise in nationalism throughout the country.

Holmes’ first appearance in the BBC series presents Benedict Cumberbatch as a Holmes who is modernized in terms of dress; however, when analyzed closely, his outfit is simply a twenty-first century model of the very outfit Paget depicted the detective in over a hundred years ago, highlighting the importance of maintaining a classic Holmes image in the BBC series as a way of celebrating British literary history. As seen in Figure 2 on the left, Cumberbatch’s Holmes is first seen in a long, black trench coat with a thick scarf which he removes to reveal a tailored suit (Moffat 8:39-9:32). While this outfit is not particularly dated in 2010, it is a somewhat unusual choice of casual dress. The outfit is also incredibly similar to Holmes standard dress in Paget’s illustrations. In an illustration for “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Paget depicts Holmes wearing an Inverness cape with a tailored suit underneath, nearly identical to the outfit Cumberbatch wears in “A Study in Pink” (Doyle 3). This decision to feature Cumberbatch dressed almost exactly as Paget’s illustration of Holmes as the first image we see of the sleuth in this modern reimagining of the character highlights how closely tied the adaptation is to its inspiration. By maintaining this close connection to Paget’s original image, Sherlock presents a new version of Holmes that is modernized to an extent while still preserving the iconic original image of the character to evoke nationalistic pride in British viewers.

Holmes’ first appearance in the BBC series presents Benedict Cumberbatch as a Holmes who is modernized in terms of dress; however, when analyzed closely, his outfit is simply a twenty-first century model of the very outfit Paget depicted the detective in over a hundred years ago, highlighting the importance of maintaining a classic Holmes image in the BBC series as a way of celebrating British literary history. As seen in Figure 2 on the left, Cumberbatch’s Holmes is first seen in a long, black trench coat with a thick scarf which he removes to reveal a tailored suit (Moffat 8:39-9:32). While this outfit is not particularly dated in 2010, it is a somewhat unusual choice of casual dress. The outfit is also incredibly similar to Holmes standard dress in Paget’s illustrations. In an illustration for “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Paget depicts Holmes wearing an Inverness cape with a tailored suit underneath, nearly identical to the outfit Cumberbatch wears in “A Study in Pink” (Doyle 3). This decision to feature Cumberbatch dressed almost exactly as Paget’s illustration of Holmes as the first image we see of the sleuth in this modern reimagining of the character highlights how closely tied the adaptation is to its inspiration. By maintaining this close connection to Paget’s original image, Sherlock presents a new version of Holmes that is modernized to an extent while still preserving the iconic original image of the character to evoke nationalistic pride in British viewers.

Sherlock’s commitment to preserving Paget’s iconic Holmes image is only further emphasized by the show’s decision to set an entire episode in a Victorian London, demonstrating a nationalistic return to Victorian England. The third season of the show concludes with a holiday special entitled “The Abominable Bride,” an alternate storyline that places Cumberbatch’s Holmes in Doyle’s 1890s England. This episode takes the series preservation of the canonical Holmes to a new level, offering exact replicas of Paget’s illustrations. While travelling by train, Watson and Holmes arrange themselves as a near-perfect replication of Paget’s illustration, “we had the compartment to ourselves,” (Gatiss and Moffat 38:25). It is no coincidence that the image Gatiss and Moffat choose to replicate in this scene is the first illustration of Holmes in his iconic deerstalker. The imagery of Holmes in his most iconic outfit as first depicted by Paget in 1892 calls back to the original text, highlighting the connection between Paget’s original Holmes and Gatiss and Moffat’s recreation. At the height of the television series’ popularity, the creators take the show back in time in a special episode filled with imagery directly from Paget’s illustrations, highlighting the nationalistic pride throughout Britain toward the sleuthing detective.

Elementary, My Dear Joan

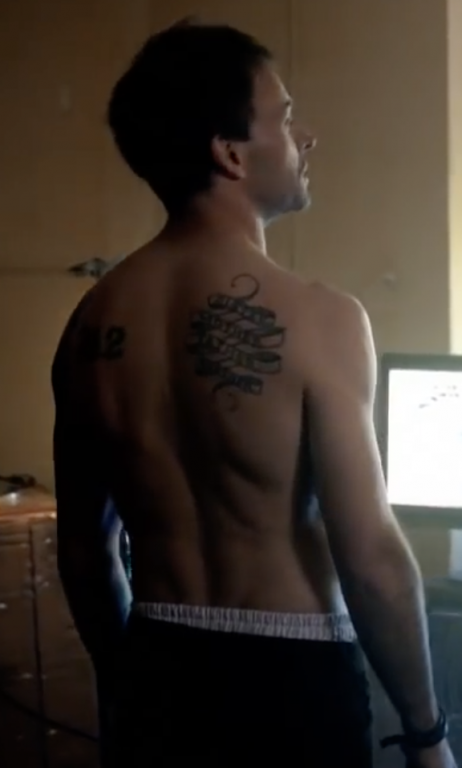

Beginning two years after Sherlock, American network CBS’s Elementary takes an entirely different route from the British adaptation, stepping away from Paget’s original model of both Holmes and Watson to create a Sherlock Holmes in keeping with the cultural moment in America in 2012. Elementary moves the iconic character, portrayed by a heavily tattooed Jonny Lee Miller, far from 221B Baker Street to Manhattan, where he lives in what he refers to as a “shoddy” brownstone owned by his father. Miller’s Holmes first appears shirtless in a pair of jeans, as seen in Figure 4 (right), offering a completely different model of Holmes than that of Paget or even Gatiss and Moffat (Doherty 3:14-5:50). This departure from Paget’s model of the sleuthing detective demonstrates to viewers right away that this is not going to be a traditional Holmes adventure.

Beginning two years after Sherlock, American network CBS’s Elementary takes an entirely different route from the British adaptation, stepping away from Paget’s original model of both Holmes and Watson to create a Sherlock Holmes in keeping with the cultural moment in America in 2012. Elementary moves the iconic character, portrayed by a heavily tattooed Jonny Lee Miller, far from 221B Baker Street to Manhattan, where he lives in what he refers to as a “shoddy” brownstone owned by his father. Miller’s Holmes first appears shirtless in a pair of jeans, as seen in Figure 4 (right), offering a completely different model of Holmes than that of Paget or even Gatiss and Moffat (Doherty 3:14-5:50). This departure from Paget’s model of the sleuthing detective demonstrates to viewers right away that this is not going to be a traditional Holmes adventure.

What is particularly interesting about Miller’s Holmes is while nothing about him looks like the Holmes Paget envisions, there is no question that he is the sleuthing detective when he arrives at his first crime scene and begins to investigate. Despite losing nearly all of the physical attributes of the iconic character, Miller’s Holmes maintains the spirit of the character by offering slight allusions the iconic character, such as through the use of a wool pea coat rather than Holmes’ traditional cape (Doherty16:00-16:55). This choice creates the illusion of a Holmes silhouette whilst still offering a contemporary spin on the outfit instead of dressing Miller’s Holmes in nearly a direct replica like Cumberbatch’s trench coat in Sherlock. By changing so much of Holmes’ appearance whilst still offering these slight nods to Paget’s vision of the character, Elementary highlights the quasi-existence of the character —a term identified by Alexius Meinong that suggests iconic characters like Sherlock Holmes are so well-known that their appearance and personality can be completely altered whilst still evoking the identity traditionally associated with them (Lapointe 64). Through the use of this quasi-existence in viewers’ memories, Elementary challenges traditional notions of Holmes while still maintaining a connection to fans of the character.

The biggest departure from Paget’s illustrations does not actually happen with Miller’s Holmes but instead with Lucy Liu’s Joan Watson. Elementary portrays Watson as an Asian-American woman who is first seen in casual gym clothes before changing into casual streetwear, as seen in Figure 5 on the left (Doherty 1:19-1:55). Not only is the choice to change Watson’s gender and race a huge departure from Doyle’s original character, the decision to completely alter the formal dress typically seen in Paget’s depictions of the character further emphasizes the CBS drama’s desire to challenge these iconic characters. Viewers see Watson before Holmes first appears on the show, and the detective is only seen by the audience when Watson meets him, maintaining the notion that Watson is the driving force of the story, much like in Doyle’s stories where Watson serves as narrator. Through maintaining Watson’s function in the show whilst completely altering her appearance, Elementary is once again able to completely turn Paget’s image of the character on its head whilst still evoking a connection with viewers that are fans of the original text through her quasi-existence.

The biggest departure from Paget’s illustrations does not actually happen with Miller’s Holmes but instead with Lucy Liu’s Joan Watson. Elementary portrays Watson as an Asian-American woman who is first seen in casual gym clothes before changing into casual streetwear, as seen in Figure 5 on the left (Doherty 1:19-1:55). Not only is the choice to change Watson’s gender and race a huge departure from Doyle’s original character, the decision to completely alter the formal dress typically seen in Paget’s depictions of the character further emphasizes the CBS drama’s desire to challenge these iconic characters. Viewers see Watson before Holmes first appears on the show, and the detective is only seen by the audience when Watson meets him, maintaining the notion that Watson is the driving force of the story, much like in Doyle’s stories where Watson serves as narrator. Through maintaining Watson’s function in the show whilst completely altering her appearance, Elementary is once again able to completely turn Paget’s image of the character on its head whilst still evoking a connection with viewers that are fans of the original text through her quasi-existence.

There is no doubt that Elementary’s choice to detach itself from Paget’s iconic image of Holmes as much as possible was intentional. When Elementary first began, the Occupy Wall Street movement —which aimed to put an end to class disparity and call to attention the struggles of the average American— was in full force across America with solidarity protests taking place in over 80 countries worldwide (Lubin 184). By taking Doyle’s upper class Holmes and Watson and transforming them into middle class New Yorkers, Elementary creates a modernized Sherlock Holmes tale that is more accessible to its intended viewers whilst still creating fantastical mysteries and adventures for the sleuth and his companion to solve. By doing so, the television series preserves the ambiance of Doyle and Paget’s iconic Holmes whilst at the same time relating the character to modern American issues.

Is This For Me? …Because He’s Dead

Is This For Me? …Because He’s Dead

One of the strangest adaptations of Sherlock Holmes in recent years is a Family Guy episode titled, “V is for Mystery.” Interestingly, this parody is the

adaptation that preserves Paget’s image of Holmes the most, exaggerating the character in a way that highlights the absurdities of the class divide in Victorian England. Family Guy characters Stewie and Brian take on the roles of Holmes and Watson, and are first seen dressed in exact replicas of their attire in Paget’s iconic illustration “we had the compartment to ourselves” (Goodman 0:10-0:20). Featuring the characters in Paget’s iconic dressings immediately draws viewer’s attention to the canonical Holmes, while at the same time, the choice to have a baby and a dog portray the duo offers an absurd contradiction to the tall, mysterious sleuth and his war-veteran companion as depicted by Paget. The absurdity of choosing this duo to take on the roles of Holmes and Watson challenges the very obsession with Holmes as a sense of British nationalist pride that Sherlock preserves.

The absurdity in this adaptation continues through humour, particularly in a scene where Holmes is asked how he found out Moriarty was the jewel thief and offers an extremely convoluted answer mentioning Moriarty’s lack of top coat, misplaced watch fob, and the bottom of his pant legs. The camera then zooms out to show jewellery falling out of Moriarty’s hat, and the thief adds, “and the jewels hanging out of my hat?” (Goodman 5:30-5:58). This deliberate exaggeration of Holmes’ science of deduction is certainly done with the intention of humour, but it also an effective method of challenging traditional beliefs about Sherlock Holmes’ deductive skills to once again counter the nationalistic pride that Britain feels towards the detective. In this sense, the American comedy evokes Reina Hayaki’s model of fictional characters as abstract objects, suggesting that anything about them can be altered and that no one model of the character is more true than another (143-144). By presenting a Holmes so entirely different in terms of intelligence but so visually similar to Paget’s original character, Family Guy turns generalized notions about the iconic detective figure on their head. Much like CBS’s Elementary, Family Guy’s choice to challenge the traditional notion of Holmes as illustrated by Paget happens in keeping with the current cultural moment in America. However, as a comedy, Family Guy does so through the use of parody, using an exaggerated version of Paget and Doyle’s Holmes to call viewers attention to the downfalls of the character, highlighting how out-of-place the upper class detective figure has become to modern American audiences.

The absurdity in this adaptation continues through humour, particularly in a scene where Holmes is asked how he found out Moriarty was the jewel thief and offers an extremely convoluted answer mentioning Moriarty’s lack of top coat, misplaced watch fob, and the bottom of his pant legs. The camera then zooms out to show jewellery falling out of Moriarty’s hat, and the thief adds, “and the jewels hanging out of my hat?” (Goodman 5:30-5:58). This deliberate exaggeration of Holmes’ science of deduction is certainly done with the intention of humour, but it also an effective method of challenging traditional beliefs about Sherlock Holmes’ deductive skills to once again counter the nationalistic pride that Britain feels towards the detective. In this sense, the American comedy evokes Reina Hayaki’s model of fictional characters as abstract objects, suggesting that anything about them can be altered and that no one model of the character is more true than another (143-144). By presenting a Holmes so entirely different in terms of intelligence but so visually similar to Paget’s original character, Family Guy turns generalized notions about the iconic detective figure on their head. Much like CBS’s Elementary, Family Guy’s choice to challenge the traditional notion of Holmes as illustrated by Paget happens in keeping with the current cultural moment in America. However, as a comedy, Family Guy does so through the use of parody, using an exaggerated version of Paget and Doyle’s Holmes to call viewers attention to the downfalls of the character, highlighting how out-of-place the upper class detective figure has become to modern American audiences.

A New Sherlock Holmes

Over one hundred years since his first collaboration with Doyle for Strand Magazine, Paget’s illustrations continue to inspire modern adaptations of the character, maintaining an established tradition of modernizing detective fiction to offer new commentary on the current cultural moment. British network BBC’s Sherlock offers a nationalistic pride in Britain through its enforcement of Paget’s iconic image, whereas American programs Elementary and Family Guy challenge this same nationalistic pride, creating a modernized Holmes that is more appealing to working class Americans either through changing the character fundamentally in Elementary or exaggerating his personality dramatically in Family Guy. Regardless, each of these three adaptations still features Paget’s iconic illustrations heavily throughout them, demonstrating just how instrumental his work was in the international success of Doyle’s sleuthing detective.

Faye Hamidavi

Works Cited

BBC. “Sherlock: A Study in Pink (Trailer) HD.” YouTube, 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=704AblLNlY8

Ashcroft, Richard T., and Mark Bevir. “British Multiculturalism after Empire: Immigration, Nationality, and Citizenship.” Multiculturalism in the British Commonwealth: Comparative Perspectives on Theory and Practice, edited by Richard T. Ashcroft and Mark Bevir, 1st ed., University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2019, pp. 25–45. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvr7fcvv.5.

Diniejko, Andrzej. “Sidney Paget, the Artist Who Illustrated the Sherlock Holmes Stories.” The Victorian Web, 2013, http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/pagets/introduction.html.

Doherty, Robert. “Pilot.” Elementary, directed by Michael Cuesta, 2012.

Doyle, Arthur Conan, Sir. The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, London: George Newnes Limited, 1892. Internet Archive, www.archive.org/details/adventuresofsher001892doyl.

Gatiss, Mark and Steven Moffat. “The Abominable Bride.” Sherlock, directed by Douglas Mackinnon, 2016.

Goodman, David. “V is for Mystery.” Family Guy, directed by Joseph Lee, 2018.

Hayaki, Reina. “Fictional Characters as Abstract Objects: Some Questions.” American Philosophical Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 2, 2009, pp. 141–49. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/ 20464446.

Lapointe, Julien. “‘He Doesn’t Look Like Sherlock Holmes:’ The Truth Value and Existential Status of Fictional Worlds and Their Characters.” World Building, edited by Marta Boni, Amsterdam University Press, 2017, pp. 62–76. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1zkjz0m.6.

Lubin, Judy. “The ‘Occupy’ Movement: Emerging Protest Forms and Contested Urban Spaces.” Berkeley Planning Journal, vol. 25, 2012, pp. 184-197, www.escholarship.org/content/qt5rb320n3/qt5rb320n3_noSplash_6400b7bc03a5....

McCraw, Neil. “Adaptation and Cultural History.” Adapting Detective Fiction: Crime, Englishness, and the TV Detectives, Continuum International Publishing, 2011, pp. 1-18.

Moffat, Steven. “A Study in Pink.” Sherlock, directed by Paul McGuigan, 2010.

Images

Figure 1: Paget, Sidney. "We had the compartment to ourselves." The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, 1891, www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/pagets/72.html.

Figure 2: "Sherlock Trailer - Season 1." The Empty Hearse, 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=xK7S9mrFWL4,

Figure 3: "Sherlock Special: Official Extended Trailer." BBC One, 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=7hjPxUfV32Q.

Figure 4: "Elementary Exclusive Preview." CBS, 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ff-XiZzJLxw.

Figure 5: "Elementary Exclusive Preview." CBS, 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ff-XiZzJLxw.

Figure 6: Goodman, David. “V is for Mystery.” Family Guy, 2018. Netflix.

Figure 7: Goodman, David. “V is for Mystery.” Family Guy, 2018. Netflix.