A key section in Barbara Black’s On Exhibit argues that FitzGerald’s translation and the eventual distribution of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám helped contribute to the fetishization of Eastern culture. The distribution of the Rubáiyát was very popular during the 19th and 20th centuries, it made a lot of money, which made it a part of the culture at the time. For example, quarto-sized books were often sold for under fifteen dollars. Concerning the text, she states that his translation showcases that he was not interested in highlighting Persian culture, but instead focused on, writing, “In certain ways, FitzGerald was determined to give an oriental flavor to his Rubáiyát, evident in his inclusion of an erudite footnote early in the text, in his use of Persian names in stanza 10 for evocative effect rather than substantive meaning…” (Black 63). From her viewpoint, FitzGerald took a piece of text that had a non-Western perspective and decided to frame it in an exaggerated fashion that contributed to the common view of the East being “exotic.”

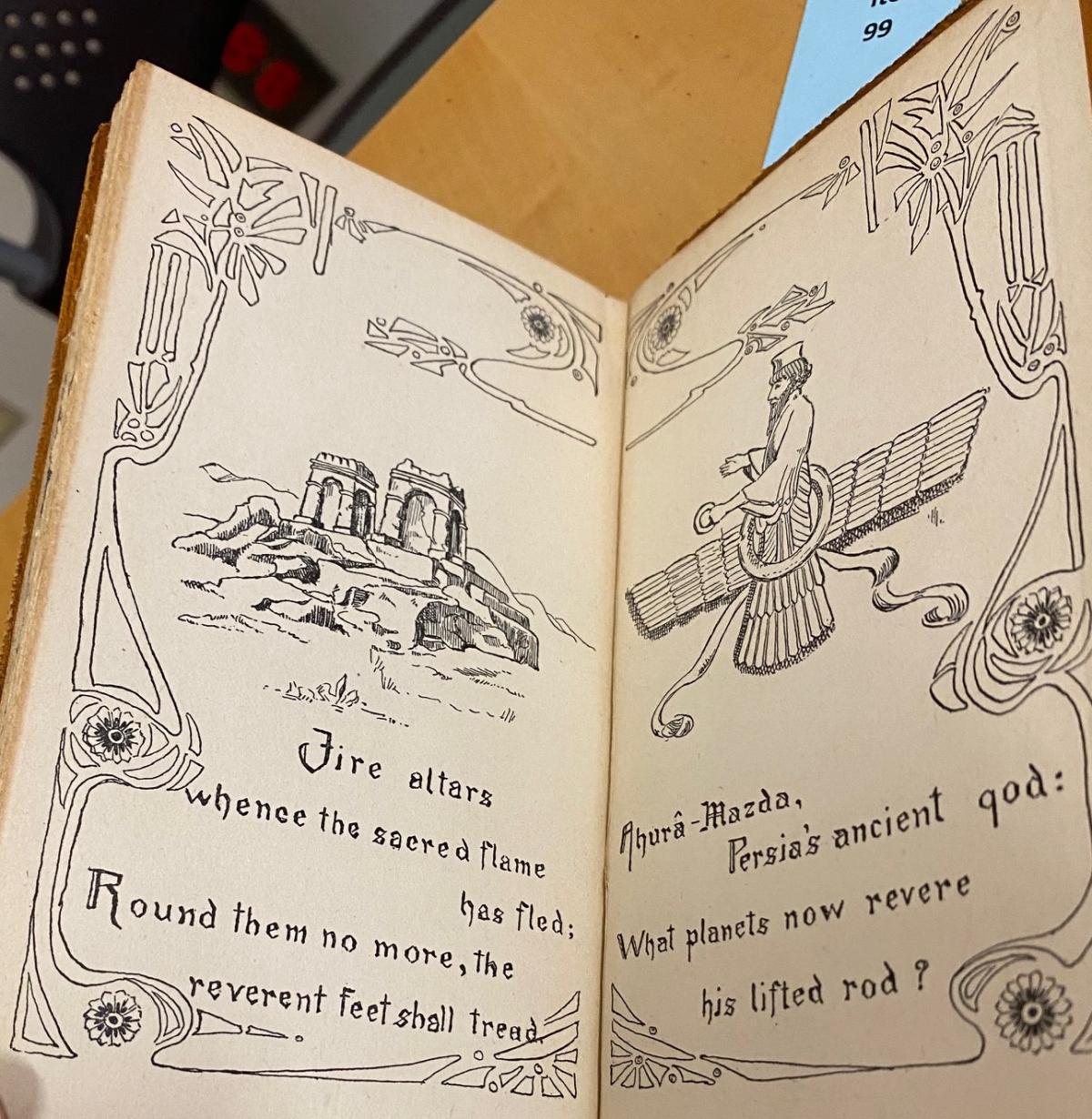

My edition demonstrates a lot of these points -- both physically and through research. The size of the book (17cm) (see figure 3 ) and the fragile/non-detailed book spine (see figure ) lead me to believe that this book may have been part of a larger mass-produced batch of books. While the size of the book does not suggest that it would be displayed on a shelf like some of the other books in this exhibit, the size and general condition of the book make the book look cheap (evident by the leather-bound material falling apart). This “cheapness” does not necessarily mean it’s Orientalist, there were plenty of books that were made throughout history that were not made to be displayed on a bookshelf.

One way it proves Black’s point about the books being Orientalist is the author’s background and the subsequent inclusion of her version in a folio-type book (see figure 2 ). Although the book itself was put together by friends and her editor, the inclusion of the Rubáiyát in a book filled with her poems retroactively positions Truesdell as the sole writer of the poem. It creates a power dynamic that makes it seem like she was the sole author of the poem and does not acknowledge the culture or history behind the poem. Yet, it also feels unfair to her, because she did not have a say in what to include in her final works. As noted in the Description of Edition exhibit, Truesdell was not connected in any way to Persian culture outside of The Soul’s Rubáiyát. This is similar to what Black discussed about Fitzgerald in On Exhibit -- Truesdell, and her friends retroactively “dressed” the poem through the words and status of Truesdell. In other words, omitting Omar Khayyám from her version, makes it seem like she wrote it, contributing to the view that the Rubáiyát are Orientalists. It raises the question of who is allowed to engage in understanding Persian culture. In this instance, racism and imperialism dating back many years have muddied the relationship between the author and the original originator. The history of how the East was fetishized by the West contributes to this West vs East dynamic.

Ultimately, the line between being a cultural consumer and being curious with no ill intentions is very thin. The lack of information about Truesdell and her not being widely talked about makes it hard to create a clear picture of who Truesdell was. This missing knowledge showcases the misogyny of the period and how women’s creative contributions were less likely to be preserved.

WORKS CITED:

Black, Barbara J. “Fugitive Articulation of an All-Obliterated Tongue: Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and the Politics of Collecting.” On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, 2000, pp. 59–63.