Barbara Black’s chapter “Fugitive Articulation” in her book On Exhibit argues that the gift book tradition of the “FitzOmar” Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám demonstrates how the Western “cult following” (59) of the poem, and its typically glamoured encasing, appropriates and participates in the orientalist-view of the East, particularly Persia. Black focuses on the aesthetics adopted by Rubáiyát fanatics, discussing the bejeweled covers used to display the book, the collection of other Persian rarities and tokens in collection with it, the dinners for Rubáiyát clubs (60) stylized in what was believed to be authentic Persian cooking, all to show how “possessing the text was as important as reading it, if not more so” (61). For Black, this objectification that resulted in widespread popularity of the poem began, and therefore was entrenched, in the high-status symbol the Rubáiyát signaled, attributing to one’s collection of curiosities that were possessed but not read, shown off, but not understood. While Black certainly establishes how the upper class’s favor of the Rubáiyát presented as objectification, appropriation, and Orientalist mystical stereotypes, she misses a key population of readers who’s status, social or otherwise, could not be changed by the mere possession of a book. While the initial popularity and proliferation of the Rubáiyát can be attributed to the wealthy and intellectual classes’ influence, the continued spread of the book extends far beyond display cases and FitzOmar clubs. When the book reached the common and lower classes, its gift-book status still continued due to the publishers’ price adjustment, offering plain, ornamental-less versions for a much cheaper price than the “twelve thousand dollars” that some of the wealthy were able to spend on FitzGerald’s works so that the general public would be able to appreciate and give to friends as well.

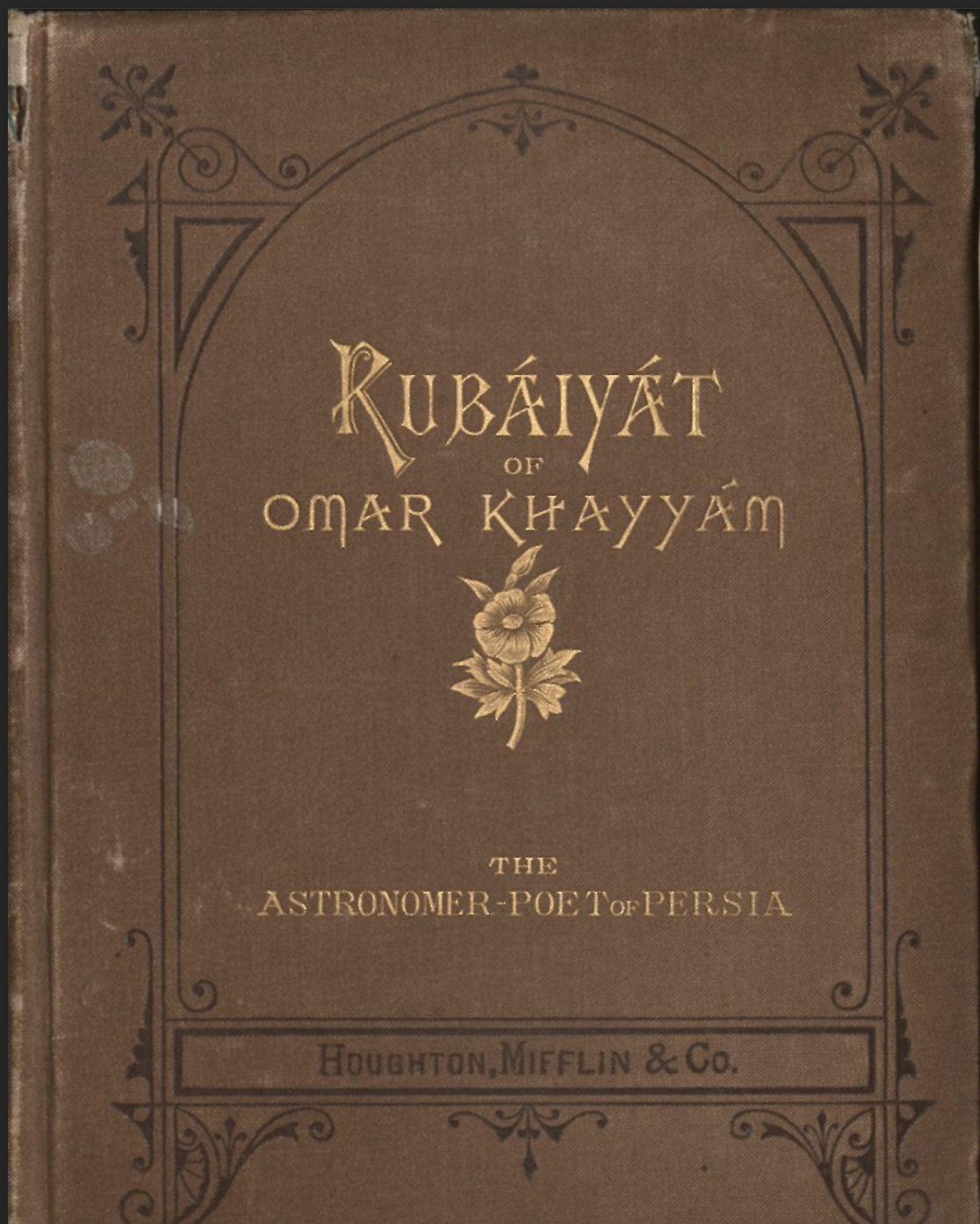

When looking at copies of the Rubáiyát that are intended for a more general populace, we are able to analyze the intended use and audience, especially in the cases of gift books that not only show us a peek into the life of the recipient, but also in how they were perceived by the gifter. For example, looking at item #7 of OSU’s collection addressed to “To The Fair Lady Lucy” from an anonymous “Lover” it is clear that this gift, despite the flowery language in the dedication, was not meant to be displayed or coveted as a personal jewel; the cover is a drab brown with minimal embellishments- the cover’s gold detailing and flower are the only illustrations present for this edition (see image 1). This lack of adornment or illustrations instead keeps the focus on the text itself, something possibly kept in mind by the gifter. Furthermore, as indicated by the advertisement in the front matter, the publishers (Houghton, Mifflin, & Co.) did offer more expensive editions of the text featuring “Ornamental Title Page and fifty-six magnificent illustrations” (see image 2). While, as Black also notes, there were many copies made available to more affluent commoners for a higher price with the fanciful features ascribed to a treasure book (59-60), we cannot ignore the prevalence of these more affordable, less decorative copies that were still chosen and given as gifts to loved ones. These gifts, in their more traditional novel-like dressing, attest to the Rubáiyát not being just a treasured, displayable “jewel,” but also a book someone can appreciate for its most basic purpose: to read.

The appreciation of Khayyám’s Rubáiyát, while at times Orientalist in its fetishization as an object to possess, can also be exclusive to some for its textual merit. While looking at people’s possessions in vacuum we must be careful to not presume intent or opinion, I do believe we can read archival pieces for indications of use and offer speculation. For example, in this edition, the (or a) owner left several brief annotations throughout the copy, signaling stanzas of note they found in their reading. One of the annotations I’d like to bring attention to is that of the markings by stanza XXXII (see image 3). While the marking is an innocuous squiggled pencil line, it demonstrates that the reader found this particular stanza important enough to make note of. This particular stanza is one of the more complex philosophies presented by the text, discussing the unknown and existence as a whole for the poem’s speaker (Me) and their beloved (Thee). The marking by it, especially for a stanza as challenging as this, illustrates to us as archivists that the owner of this text truly took interest in the philosophical ideas expressed by Khayyám and FitzGerald. Rather than marking a stanza that discusses pleasures, wine, or other commonly exoticized facets of Khayyám's ideas, the reader instead engaged with the text for the theoretical questions it posed.

FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám poses a significant issue in regards to Western Orientalism, but its widespread popularity and status of a giftbook is not all-encompassing as a gross negative. As the poem’s popularity allowed for publishers to manufacturer more financially accessible versions of the text, commoners and lower classes engaged with the FitzOmar Rubáiyát’s sentiments and cultural critiques, sometimes, yes, in the vein of Orientalist fantasy, but also in appreciation and education of the authors’ verse. As archivists have a duty to look for moments in history that contain Western biases and problematize them, we also must take a nuanced approach to how cross cultural texts such as these impact people in a multitude of ways.

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit : Victorians and Their Museums. Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 59–64.

Khayyám, Omar. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: The Astronomer-Poet of Persia. Translated by Edward FitzGerald, 14th ed., Boston, MA, Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1888.