Harrison Weir was considered a "man of many parts" (Simon Cooke, Victorian Web). He was an animal artist of the nineteenth century, naturalist, ornithologist, horticulturist, an advocate of animal rights, and lover of animals. These four Weir illustrations display his vision that parallels exist between humans and animals.

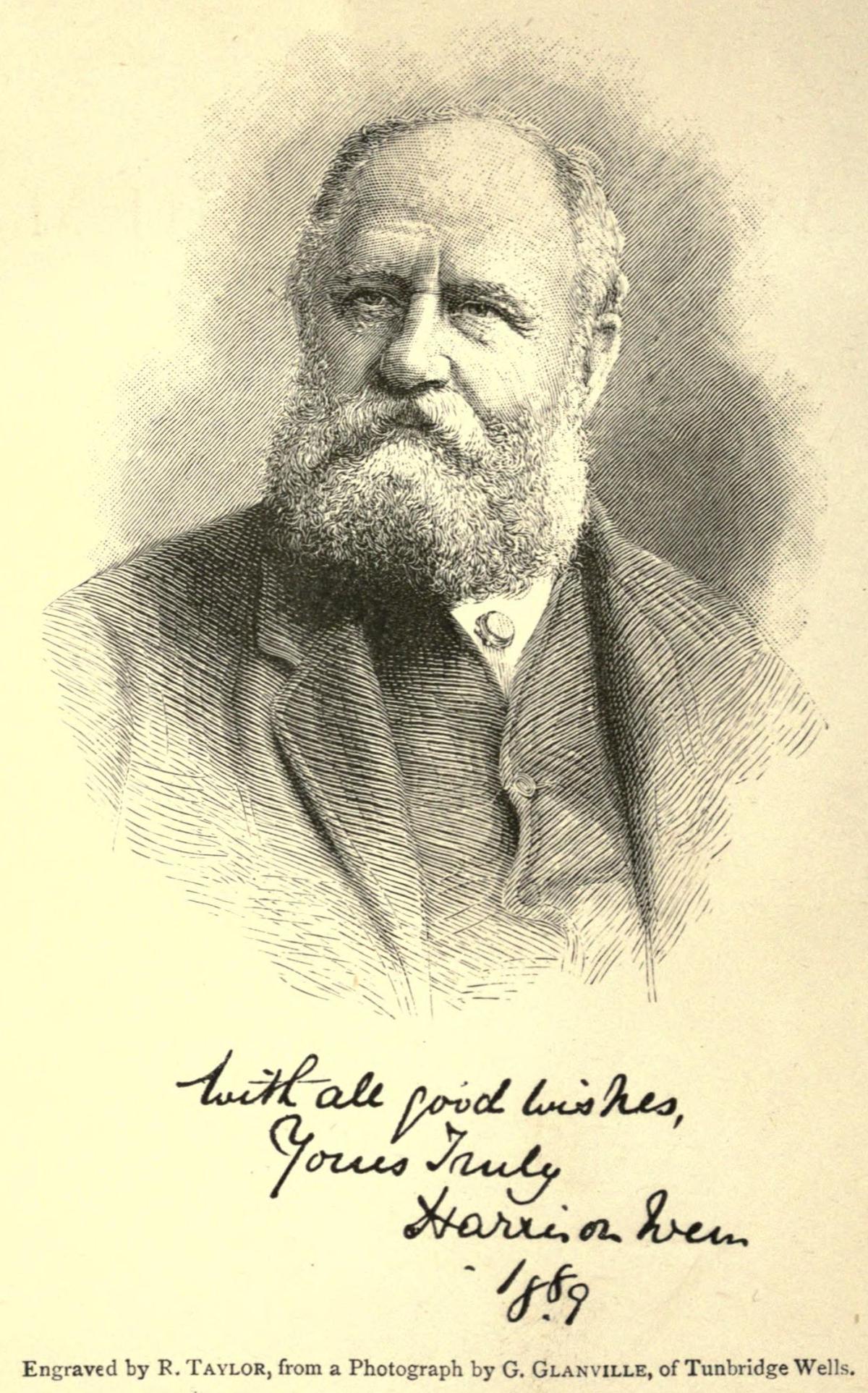

Harrison Weir (1824-1906)—"The Father of the Cat Fancy," engraved from a photograph by R. Taylor, 1889. Weir lived in pursuit of knowledge and was fascinated by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and the pseudo-scientific theory of physiognomy. He established the first cat show in England at The Crystal Palace in 1871 where domesticated and fancy cats were judged. He was a skilled animal painter, and many of his artworks appeared in children's books and magazines.

Harrison Weir, "Fidelity," for The Poetry of Nature, 1861, illustrated and collected work by Harrison Weir, The Victorian Web, scanned by Simon Cooke. This first book illustration presents Weir's interest in anthropmorphism; named "Fidelity," the dog stands guard faithfully and mourns his master whose body is indicated through a fallen hat set among sharp rocks. Weir's dog displays a canine's need to protect his master. The dog seems human-like in his behavior but also signifies a morality of his own. In this case, the dog is looking to his master, saddened by his fall and unable to reach him. Perching on its two front legs and showing the viewer its sulking eyes and mouth, the dog expresses concern and reflects moral actions by staying rooted in place.

Harrison Weir, "The Literary Dog," for Funny Dogs with Funny Tales, by James Hannay, 1857, The Victorian Web, scanned by Simon Cooke. This second illustration is an anthropomorphic drawing of a grown mid-Victorian middle-class dog, cast in the role of a struggling writer living on Grub Street in Caneville. Weir and many other writers, including Hannay and Elwes, collaborated on various tales of animals depicted in the guise of Victorians, presenting society in a satirical manner. The use of the literary dog's lamp, books on shelves, paper, quill pen, and writing desk are objects that Weir uses to epitomize the studious behavior of a Victorian writer captivated in his work. The dog's resilience to keep writing while the oil lamp is lit allows the audience to suggest that his work is the most crucial part of his day. Weir's use of the dog to refer to the animal's strength and determination recalls traits of humans and their literary passions.

Harrison Weir, "Consolation," for The Adventures of a Dog, and a Good Dog Too, by Alfred Elwes, 1858, The Victorian Web, scanned by Simon Cooke. This third illustration displays a canine family that takes care of one another. Weir's illustration for Elwes's story exemplifies his interests in anthropomorphizing dogs. In the preface, Elwes says, "...education, connections, the society they keep, have all their influence," indicating that dogs are governed by human nature and perform with similar emotions and actions as thehuman beings around them. Elwes describes a moment where a dying canine named Lupo lays in bed surrounded by little, crying dogs, who are his children. The little dogs rush to the canine dressed in a fine red suit, hoping he could help save their father. Weir's use of emotions and good morale of the canine gentlemen shows his role as a "human" savior, who holds the future of the little dogs in his paws.

Harrison Weir, "A Very Great Bear," for The Adventures of a Bear, by Alfred Elwes, 1853, The Victorian Web, scanned by Simon Cooke. This fourth illustration is an anthropomorphic bear flaunting his "new dress" in respectable middle-class society. Weir's satirical illustration uses animals to show the extremities of Victorian society's poshness and snobbishness. Elwes's animals dressed as Victorians enable the audience to be entertained but also enlightened. Elwes presents a story about a bear named Bruin, who is bad-tempered and journeys from his paternal home in search of his true self. On his journey, Bruin has few successes and many failures as he comes across other animals who teach him the ways of Victorian life in the society of Caneville. Here Weir depicts Bruin wearing a top hat, coat, vest, cravat, pocket watch, and trousers, holding a walking stick as other animals admire him. The cat tips off his hat towards the bear, signifying she sees him as an elite member of society; a kitten crosses her paws behind herself with deference. The character behind him in a bonnet and dress, Miss. Greyhound, watches him peculiarly, probably contemplative about the "bear gentleman's" true nature. Weir's bear poses as a "gentleman," capturing the desire to be elevated in Victorian society, leading some Victorians to imitate those of a higher class.