The misuse and exploitation of the Victorian horse is the focus of this case. Horses were essential to Victorian life for transportation and farming and also served as a vital tool for industrialization in Britain. Disturbed by the abuse of horses she witnessed, Anna Sewell (1820-78) published Black Beauty in 1877 in the hopes of fighting the mistreatment. Through her work, she gave the horses their own voices to advocate for equine rights. With illustrations from Black Beauty and other Victorian sources, this case reveals the dark fate of a Victorian horse for the world to see in the hopes of inspiring change.

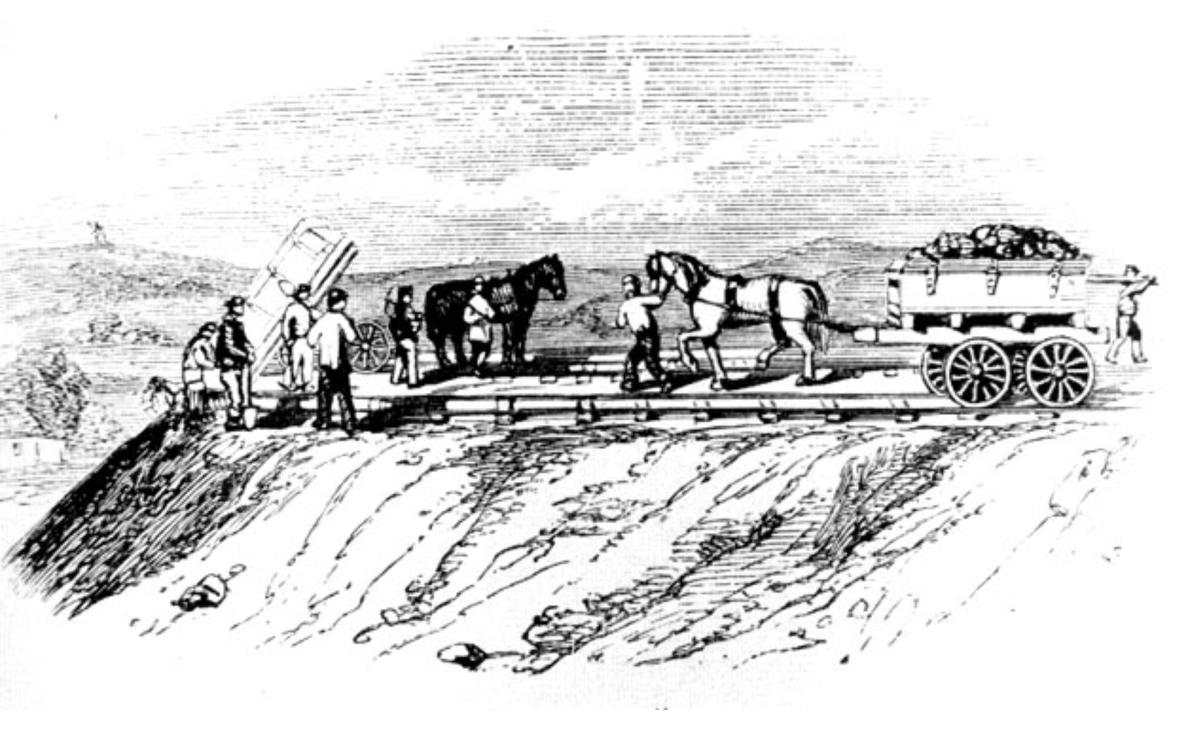

“Tipping,” London-Birmingham Railway, 1830s. This first illustration depicts the horse at work, moving heavy supplies. This illustration represents the significance that the horse played in the rise of the industrialization of England at the time. It is evident that these horses depicted are not there for companionship but rather to perform a demanding job in building railways that revolutionized life in Victorian Britain. Work horses were forced to toil beyond their capabilities and would often suffer the consequences of this taxing and stressful lifestyle.

George Cruikshank, “A Dead Horse Being Dragged to the Knacker’s Yard,” Sunday in London, by John Wright, 1833. In this second illustration, a dead horse is being carted away to the knacker’s yard. This horse has been worked to death and is now being thrown into a cart and will be disposed of. This horse is meant to represent all of the working horses that were mistreated and then discarded afterward. It is clear that the humans in this illustration do not care about the animals at all. The pedestrians in the street do not even glance at the dead horse being carted through the street, and the men driving the carriage are smoking and chatting. One man even seems as though he is about to whip the horse driving the cart, showing cold-hearted abuse. In some ways this illustration also shows how little one horse mattered in the grand scheme of things; if one horse were to die, its replacement was already there, waiting to cart away another dead carcass. This image shows how deeply engrained the horse was to Victorian society as a tool, more than a living creature.

Cover, Black Beauty, Young Folk’s Edition, by Anna Sewell, 1902. This third illustration is one of the covers of Black Beauty, published in 1902, 25 years after the original. In writing Black Beauty, Sewell hoped to shine a light on the abuse that horses endured by giving a voice to Black Beauty, the equine narrator of the entire book. This publication chooses a very detailed and life-like painting of Black Beauty for the cover. The fine details in his face, the bulging eyes, the veins, and the pricked ears all serve Sewell’s original purpose: to make the public understand the reality of a horse's often dire situation. Sewell’s novel, still popular today, was so highly regarded in the nineteenth century that she was even acknowledged by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

“The Head Hung Out of the Cart Tail,” Black Beauty, by Anna Sewell, 1877, from Young Folks edition, 1902. This final illustration in the case comes from Sewell’s novel, and it depicts one of Black Beauty’s friends, Ginger, being carted away. Unlike Cruikshank’s illustration (image 2), this horse’s head is hanging out of the cart and is the only thing the viewer really sees. Sewell makes a point of highlighting the utter trauma and pain that Ginger has endured throughout her life as a slave to humans. Because Ginger becomes Black Beauty's friend, and we know her narrative, it is even more heartbreaking to see her lifeless body carted away, knowing that this is the "kindest" the world has ever been to her. In the novel, Black Beauty finds relief in knowing that Ginger is dead because the world could not hurt her anymore. Sewell, like Cruikshank, has taken the image of the dead horse and made it personal and, therefore, more impactful.