The legacy of the elephant in a green suit began as an entertaining bedtime story from two parents for their children. The tender care, delight, and leisure the story cultivates is a far cry from early didactic children's literature and represents the evolved benevolent intentions for the genre. When Cécile de Brunhoff thought up the story and Jean de Brunhoff illustrated its pictures, the two didn't plan for their gift to nurture and entertain thousands of children other than their own. But, that's exactly what it grew to do. The consequences of the proliferation of the story and its less admirable qualities are worth investigating. The plot of The Story of Babar: The Little Elephant is influenced by the surrounding sensibilities around progress and civilization that are informed by colonization and that De Brunhoff lived through. Unintentionally, it may continue to communicate these things.

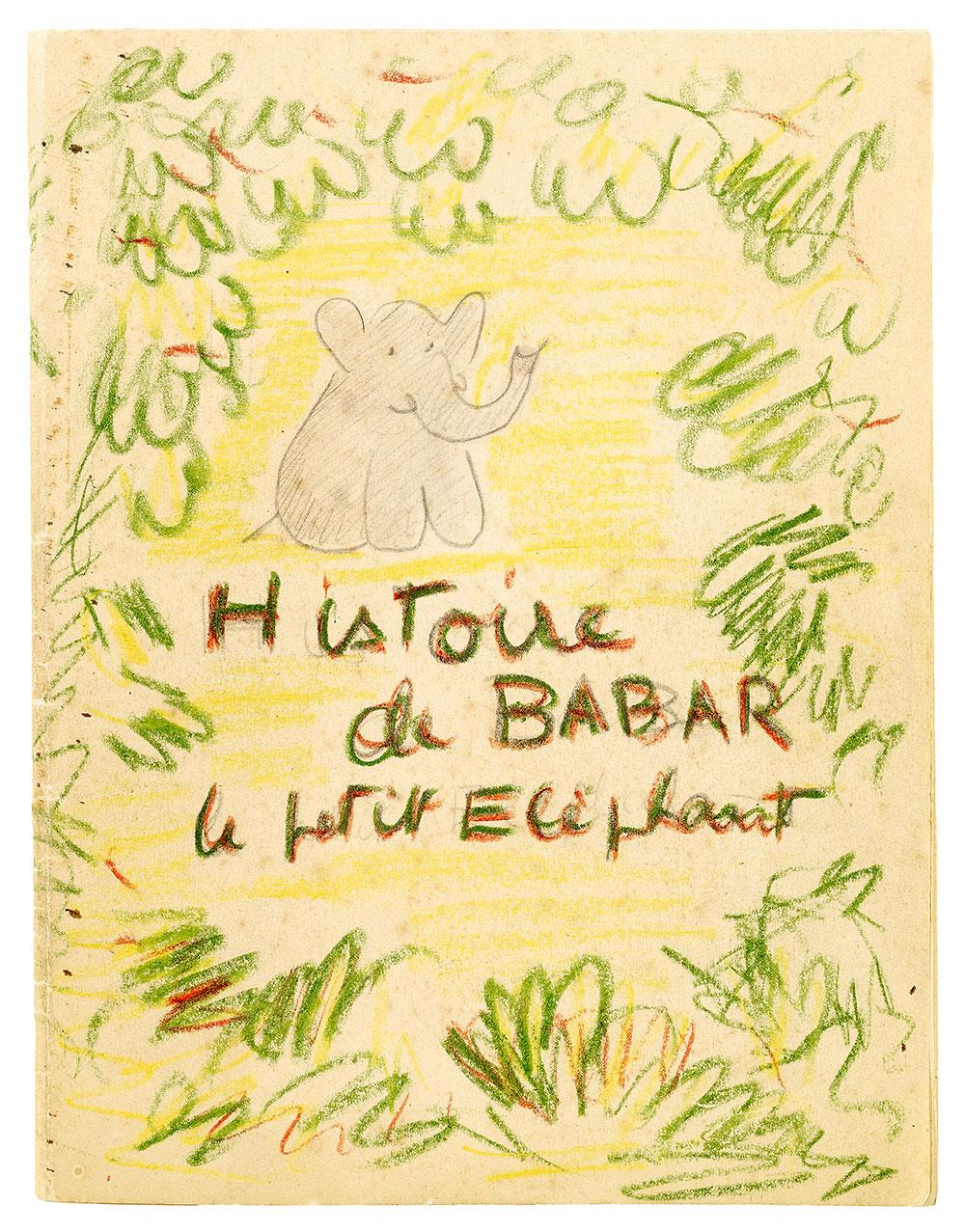

Jean de Brunhoff, Histoire de Babar, Le Petit Éléphant (The Story of Babar), 1930-1931, The Morgan Collection.

This crayon-marked amateur drawing, perhaps, best illustrates the tender intentions behind The Story of Babar: The Little Elephant. This was the story's original cover page. Each element of the image conveys a homemade feel. De Brunhoff does not use ink or even pencils but, the aforementioned crayons color the page. The simplicity of his drawings distances his work from professionalism and aligns his work with innocent sketches. Even the rough, yellow notebook paper that he draws on is obscene for work intended for publication but perfect for small gifts. This image is not official. It's not even signed. It was intended for his children and for their eyes only. This homemade feel initiates the domino effect for assumptions made on the genuineness and purity of this work. A “homemade” status might signal that it’s one of a kind. Its intention was to be the best it could be for its recipient, not to be mass-produced. The story was made out of love and not for profit. Its unrefinedness must mean that it is a spontaneous production of the heart. “Homemade” leads to assumptions on its process. The best must not have been available, yet the creator used creative methods to achieve their goal. A “homemade” feel reduces assumptions about complexity. The cover is plain but that plainness is endearing. It’s cute. It’s as innocent as the children that it is was intended for.

However, De Brunhoff did apply effort to his gift. The Morgan Library indicates that he had “earlier drafts.” This information does not and could never object to how much Jean de Brunhoff loved his children, but it may help introduce hesitancy to assume things. Is The Story of Babar as simple as one might assume? Is it absolutely innocent?

After deciding to publish this bedtime story, De Brunhoff made significant revisions. He added text and added new scenes. As early as page one, the versions diverge. This image depicts the first page of the “homemade” Story of Babar and the published Story of Babar. The original immediately has Babar’s mother shot by the hunter. In his published version, De Brunhoff chose to elaborate more on the relationship between Babar and his mother and life within the wild savannah that Babar lives in. Without even understanding the content, the reader sees how the visuals and structure of the two versions differ strikingly. Still, understanding that content widens the chasm between the two and can have us begin to question De Brunhoff’s intentions. On the left, murder, tears, and tragedy open this story for children. On the right, a mother and her child play peacefully. While the composition of the former can be used to dispel the previously noted “cute” nature of the story, it better serves to reveal De Brunhoff’s differing goals. The original was a bedtime story. Belaboring on narrative details defeats its purpose to help his sons fall asleep. This means the story must be concise and brief, which, then, means that he reaches the plot points faster. The published story could be read at any time. It could be stopped at any moment. The increase in time that audiences spend with the story might mean that holes need to be covered up and questions should be answered. Things need to make sense. Thus, De Brunhoff is free to contextualize things—and contextualize is exactly what this does. These new elements are not filler. Rather, they work to clarify themes and motivations for the story. In the published version, Babar has more clearly lost something. Readers can imagine this because it is shown to them. When his home, family, and security are stolen from him, both readers and Babar, himself, desire for them to be restored. The city presents itself as a restorative agent rather than just a fun little place that it may have been in the “homemade” version. Readers can now make a proper comparison between life in the wildness and life in the city. The city looks much better because of it. Babar was vulnerable in his old home. He finds safety in the civilized world.

Unknown, Exposition Coloniale Internationale De Paris: Temple D'Angor Vat, 1931.

This photo, though seemingly unrelated to Babar, is part and parcel for a critical understanding of The Story of Babar: The Little Elephant. This photo was taken at the Paris Colonial Exposition in 1931—the same year that De Brunhoff wrote and published Babar. The event “functioned something like a visual report card intended to display the so-called successes of the colonial powers” (https://nextshark.com/colonialism-kids-racist-origins-babar-elephant/). France celebrated its conquest of other lands. The French imparted “civility.” The government believed it earnestly improved the lives of nations that would’ve been lost otherwise and sponsored tours to prove it to its people. The existence of such a masturbatory practice in De Brunhoff’s country of origin can help the beginnings of suspicions on the presence of this bias, but it’s the elements of his book that can prove this exhibit’s point.

Babar doesn’t just find safety in the city. He acquires education, skills, a home, a guardian, peace of mind, and wealth. Just his entrance into the city alone leads him down the path to sweeping recovery. Babar immediately encounters a sympathetic woman and has his tangible and intangible needs met. The story presents a subtle adoration and exaltation of the city. Although Babar “misses playing in the great forest,” he doesn’t return there without bringing what he’s gained from it back with him. He returns and tames the old land with the new things he’s learned. The city is a force that permanently alters the status quo. And by all accounts, it changes Babar’s life for the better. He has greater wealth and greater status with seemingly zero negative repercussions. This absolutist portrayal of city reflects the popular mindset of De Brunhoff’s time that justified colonization and created amusement parks out of gutted indigenous monuments. The city is an allegory for “civility” while Babar’s savannah is the wild land. De Brunhoff also racializes the two places by drawing a city that is exclusively white and a savannah that is vaguely African due to its animals and geography.

Interestingly, De Brunhoff seemingly argues against himself since the hunter that destroys the peace of Babar and creates the danger of the savannah comes from the city. Is this too much of a stretch? Not really. Just as many of us are educated that colonization was exploitative and wrong by our contemporary society, De Brunhoff was educated that it was, not just okay, but right, by his. That deep rooted idea of truth unconsciously makes its way into his story—even if was intended for children. His unconscious bias covers his story’s holes too.

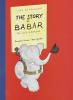

Jean de Brunhoff, The Story of Babar: The Little Elephant, Random House, 1961 Version.

This image is the cover for the published version of The Story of Babar: The Little Elephant. This image is integral to the story because of what it depicts and what it represents. First and most saliently, the cover depicts Babar standing on two legs with a hat in his trunk. Looking more deeply, we note, if we compare it to the cover of the original draft, lines are bolder and colors are more distinctive as De Brunhoff has increased the professionalism of the story. Like the assumed reasoning for his increased contextualization, it is done so—and done so fairly—because of the standards for published work. The “homemade” feel has completely disappeared. However, the exhibit acknowledges De Brunhoff’s autonomy; Just as De Brunhoff chose what to contextualize and thematize, De Brunhoff makes deliberate decisions here with the authority as the book’s only illustrator. The work still holds onto a “cute” and “childlike” aura because De Brunhoff chose to keep his simple drawing style and color his drawings softly to imitate crayon scribbles that children may recognize.

De Brunhoff’s choice to stand Babar up rather than depict him as a quadruped is of extreme note. Babar only begins walking on two feet when he enters the city and is indoctrinated by city life. Relatedly, also different is the cover’s environment. The “homemade” version has Babar in a wilderness. The published version has him standing in an empty, seemingly neutral, area, but his bipedalism suggests that he is likely in the city. Covers convey messages. Whether intended to or not, they do so as the first thing that people see and as what people project onto the story. This cover has not changed in the 60+ years of its publication. This cover primes a message about the process by which one advances oneself and the importance of being “dignified.” People associate The Story of Babar: The Little Elephant with Babar walking upright, and walking this way is associated with “civilization” in the story. The contrastof the covers between versions only works to emphasize this bias. It’s as if De Brunhoff felt the need to stress Babar’s change in civility when presenting the tale to a wider audience. Lastly, but of equal importance to this point, a U.S. publishing house is credited on the cover. This indicates the story’s popularity and the prospect of its international reach. This story has moved beyond a private bedtime story. This message about civility and evolution is plastered worldwide.