Created by Caeley Wybrow on Thu, 04/18/2024 - 23:20

Description:

Introduction to Legally Bound and Unbound

In the 19th century, Britain experienced profound social and economic transformations. The Industrial Revolution swept across the nation, giving rise to factories where machinery hummed and workers labored tirelessly in often deplorable conditions. Against this backdrop, Charles Dickens penned his novel ‘Hard Times,’ a scathing critique of the dehumanizing effects of poor working conditions and the stark divide between the privileged 1% and the 99%. These vivid images shed light on the intricate web of labor laws that shaped workers’ lives during this tumultuous era. From the Factory Acts to the struggles of unionization, legal reforms aimed to address the inequities faced by the working class. Dickens’ portrayal of factory life and the plight of characters also provides insight into the challenges endured by the British 99% in the 19th century.

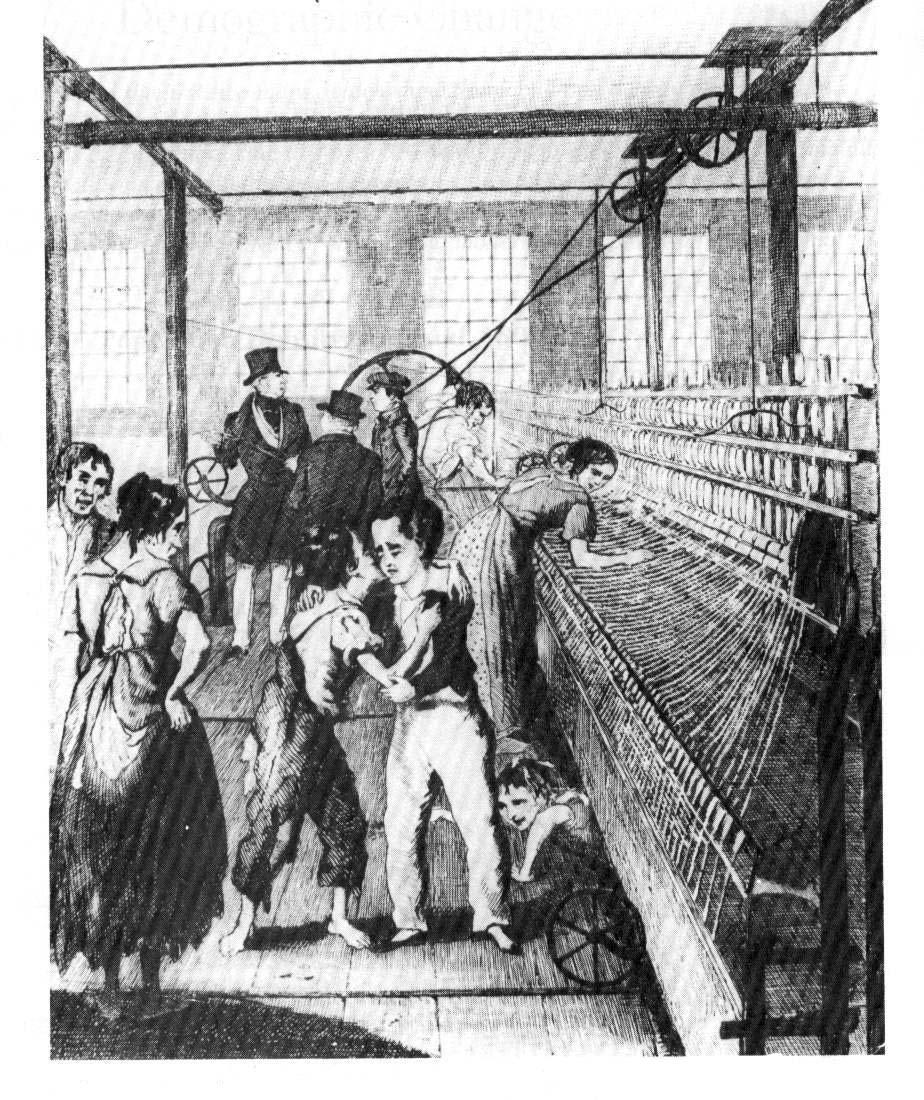

Figure 1: Legal Allowances with Regard to Labor - Chaloner, W. H. “Mrs. Trollope and the Early Factory System.” Victorian Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 1960, pp. 159–66. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3825387.

While many might be familiar with filling out a pay stub or a W-2 form in order to work today, 1800s Britain was a far cry from the legal protections and laws the twenty-first century enjoys. Adult labor in 19th century Britain was known for its profit over people-centric ideology, often denoted by workers experiencing long hours, low pay, low societal respect, a heavy burden on their body, and much more. Throughout the rapid British industrialization during the nineteenth century, the government had maintained a laissez-faire, or hands-off, attitude toward the economy, allowing the employers to do more or less as they pleased.

In this image, one can delve into the conditions of factory life. The scene portrayed in this drawing reveals the tragic reality faced by factory workers: from poor air quality and physical strain to the risk of losing body parts to the machinery before them. What remains unseen in these images is the extensive amount of time these individuals spent in that very spot within the factory. Their hours far exceeded what anyone could discern from merely analyzing the photograph. The laws aimed at regulating these conditions often required medical intervention to protect workers. For instance, there were limits on working hours for women and children, but shockingly, no such limits existed for men. This disparity highlights how certain parties were slightly shielded, while others remained just as vulnerable as before the laws were enacted. It's crucial to recognize that while these regulations adjusted workplace standards, they did little to improve societal respect for these laborers.

Figure 2: The Problems with Parliament’s Labor Laws - “File:Coat of Arms of George, Prince of Wales and Prince Regent (1762-1820).Svg.” Wikipedia, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_Arms_of_George,_Prince_of_W...(1762-1820).svg.

This image depicts a symbol intended to represent the goodness and justice of government—the crest of the British Parliament. However, despite its lofty symbolism, it failed to bring about significant improvements in worker conditions during the 19th century. Most of the laws enacted during that time were inadequate in addressing the needs of low-class workers in Britain. In a famous piece of literature that dissects the effects of British industrialization, Hard Times by Charles Dickens, one of the characters speaks to his employer in regard to lawmaking. In Book the Second, Chapter 5 a poor worker named Stephen Blackpool says to his wealthy higher class employer Josiah Bounderby, “Look how you considers of us, and writes of us, and talks of us, and goes up wi’ your deputations to Secretaries o’ State ‘bout us, and how yo are awlus right, and how we are awlus wrong….” (Dickens). Many of the 99% did not feel love from Parliament, but rather resentment and a lack of true concern. While several laws were passed such as the Factory Act of 1833 or the Workmen’s Compensation Act 1897, they were not what the 99% needed. There was a balance to be had, the people needed better conditions and higher wages, but if laws restricted the hours they would not be able to afford to live. This was one of many aspects of conflict that the above image, the crest of the British Parliament, had for the 99% in the 19th century.

Figure 3: Respecting the 99%: Legally and Socially - “Print; Pamphlet.” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1977-U-1456.

Even thought there were now new laws in place for laborers, that did not come with an increase in respect from society, especially the 1%. The image is of a British pamphlet from 1840. The artist George Cruikshank created a remarkable pamphlet titled "The British Beehive." This intricate illustration portrays British society as a hierarchical beehive, with each member occupying a designated place and role within the larger structure of industry and commerce. The beehive is divided into individual cells, each representing a specific profession or institution. At the pinnacle of the hive, we find the monarchy, followed by politics, religion, law, arts and sciences, trades, agriculture, the bank, and the military and navy. Interestingly, this visual representation does not convey the emotions of the time, but it does lay out the hierarchy of professions prevalent during that era. Notably, Parliament and factory owners, such as Bounderby from Charles Dickens' novel "Hard Times," occupy the upper echelons of the hive. In contrast, everyday workers—the 99%—are positioned at the bottom. While the laws enacted during this period did not directly alter the social atmosphere surrounding the working class, they did provide a slightly stronger foundation for workers as they entered the workforce¹². George Cruikshank's artwork serves as a fascinating commentary on the social and political dynamics of 19th-century Britain.

Figure 4: The Theoretical Benefits versus the Real Response - Bhardwaj, Shubhangi. “The List of Top 50 Richest Currency in The World.” Newsblare, 5 May 2023, https://newsblare.com/opinion/economic-finance/richest-currency-in-the-w....

As the number of labor laws increased in 19th century Britain, one would think that the 99%, those working under those labor laws, would be relieved at the increasing legal bounds of labor they had. Unfortunately, many of the 99%, as the name denotes, did not live wealthy lives. The common British worker lived off very little, and were constantly working and wishing for more money to live. Labor laws took away their opportunities to earn more money. The limited hours should mean more time for rest and play, more time for parents to spend with their children, but instead it meant less coins in their pockets, less money for necessities. The saying goes, “There is a flip side to every coin” and the flip side of laborers being bound to new regulations was less pay. In a time of survival, one does not worry so much about the conditions, but rather how they shall live through it. This was the unfortunate case for many. As new labor laws imposed upon employees and employers alike, the battle for money continued. Many workers, now limited in hours, would go on strikes. Yet the idea of always working was not pleasant or feasible either. Charles Dicken’s Hard Times sheds light on some of these sentiments. In Book 3 Chapter 8, character Mr. Sleary says “they can't be alwayth a working, they an't made for it.” (Dickens). The role of money is perhaps the hallmark of the delineation between the 1% and the 99% in the world. This is as true in the 21st century as it was in the 19th century. For many, money plays an impactful role in their lives. This is why the final image of this gallery fittingly shows the British pound silver. These shiny new coins are imposed over a British flag, making a nationalistic statement of monetary means. Just one of these coins, however, was not easy to come by in the 19th century. Numerologist C.R. Dobson is cited as saying the “most important single source of industrial conflict was the money wage.”

Works Cited:

Bhardwaj, Shubhangi. “The List of Top 50 Richest Currency in The World.” Newsblare, 5 May

2023, https://newsblare.com/opinion/economic-finance/richest-currency-in-the-w...

Cartwright, Mark. “Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution.” World History

Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2216/child-labour-in-the-british-in...

Chaloner, W. H. “Mrs. Trollope and the Early Factory System.” Victorian Studies, vol. 4, no. 2,

1960, pp. 159–66. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3825387.

Dickens, Charles. Hard Times. Wordsworth Editions, 1995.

“File:Coat of Arms of George, Prince of Wales and Prince Regent (1762-1820).Svg.” Wikipedia,

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_Arms_of_George,_Prince_of_W...(1762-1820).svg.

Linebaugh, Peter. “Laboring People in Eighteenth-Century England.” International Labor and

Working-Class History, no. 23, 1983, pp. 1–8. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27671437.

“Print; Pamphlet.” The British Museum,

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1977-U-1456.

Stephen. “Victorian MONEY Secrets: 19th Century UK Coins Revealed.” Semilla de

Botjael, https://19thcentury.us/19th-century-british-currency/.