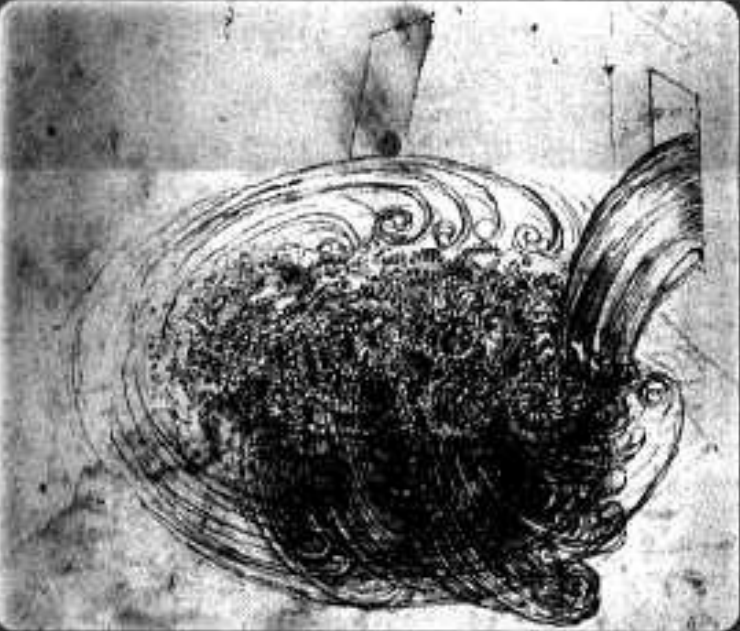

Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch of water exiting a square hole into a pool was “perhaps the first use of visualization as a scientific tool to study turbulent flow” (Gad-El-Hak). In the modern era, flow visualization is an entire industry, in which complex models and computer programs are used to simulate flow patterns. For example, in the field of computational fluid dynamics, NASA uses computer programs to visualize how modifying structural geometries impacts stresses, deformations, and velocities that a material must endure (ANSYS). However, in the Renaissance, the only interpretations of flow were those that could be seen with the naked eye.

Not only was the visual image that Leonardo crafted revolutionary for its time, but the description that he attached to it was also telling of his forward-thinking. Leonardo compared the water to something tangible he could reference and used this to explain a proposition he had for fluid dynamic properties. He wrote, “the motion of the surface of the water, which resembles that of hair, which has two motions, of which one is caused by the weight of the hair, the other by the direction of the curls” (Gad-El-Hak). This way of describing eddying motions was not only correct in interpretation, but easy to understand. The use of hair as a qualitative descriptor allows even scientifically illiterate people to understand the point he is making.

Citations:

“ANSYS Discovery Live.” NASA, NASA, www.nas.nasa.gov/publications/ams/2017/10-05-17.html.

Gad-El-Hak, Mohamed. “Fluid Mechanics from the Beginning to the Third Millennium.” International Applied Mechanics, vol. 14, no. 3, 1998, pp. 177–185., doi:10.1007/bf02681956.

Image:

Gad-El-Hak, Mohamed. “Fluid Mechanics from the Beginning to the Third Millennium.” International Applied Mechanics, vol. 14, no. 3, 1998, pp. 177–185., doi:10.1007/bf02681956.