Lewis Carroll's beloved Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) initiated a shift in children's literature from didacticism to entertainment. Carroll's use of poetry throughout his book ironically reinforces the didactic ideals of Victorian writers, while providing whimsy and humor for young readers and adults alike. Carroll places his parodies in conversations among characters and uses their reactions as a way to still enforce their value to young children as lessons to learn from. By parodying the poems of didactic writers such as Isaac Watts and Robert Southey, Carroll keeps their works alive today, while maintaining the importance of entertainment in literature.

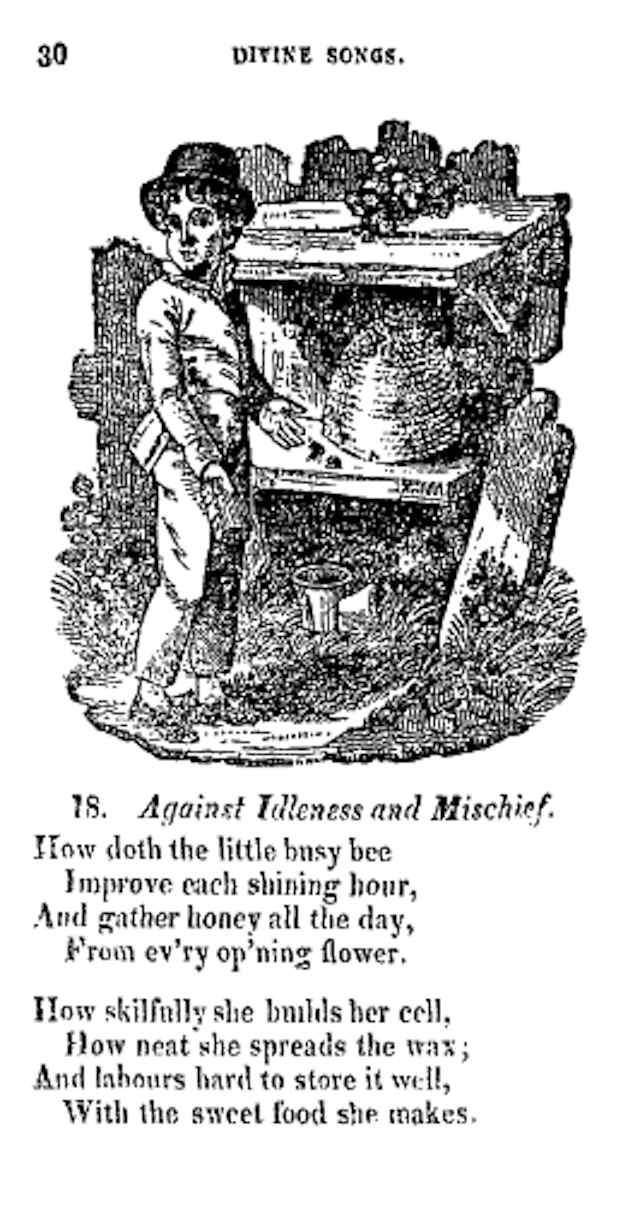

"Against Idleness and Mischief," from Divine Songs (1715), by Isaac Watts, Illustrator unknown.

This image illustrates the first two stanzas of Isaac Watts's poem "Against Idleness and Mischief," which Carroll parodies as Alice tries to recite it as a means to collect herself after falling down the rabbit hole. This illustration to Watts's original poem details the doings of an industrious bee who is always working hard to fulfill her needs while Carroll's version describes a very different animal both in physical nature and work ethic. Carroll writes of a lounging crocodile, who, unlike the busy bee, does not work hard at all and instead "neatly spreads his claws, and welcomes little fishes in, with gently smiling jaws!" Carroll takes Watts's lesson on the benefits of hard work and writes his own poem to give a a silly example of what young readers should not be modeling. Upon reciting this version of the poem, Alice is very distraught and arguably reinforces the idea that the silly parody is indeed wrong: Watts's original message is the one that should be remembered.

John Tenniel, “Father William Standing on his Head,” from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), by Lewis Carroll.

John Tenniel, "Father William Turning a Back Somersault," from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), by Lewis Carroll.

These two images come from a section of Carroll's story when Alice is trying to recall another poem she learned in school. This poem, entitled “The Old Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them” by Robert Southey, follows an old man attributing his health and good nature to his faith in God. However, Alice begins to recite a very different poem (as illustrated) that credits his status to nonsense and play as well as arguing with his wife. The Caterpillar serves to keep Alice (and the reader) in check by shutting down her silly poem and reminding her that it is incorrect, saying, "'It is wrong from beginning to end.'" Once again, Carroll entertains his readers with a silly poem while also reinforcing the idea that the didactic literature of the time should be thought of and arguably abided by. This is among the most famous of Carroll's parodied poems in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and also serves as a reminder that Carroll, in creating parodies, keeps the works of didactic writers alive today, even if their words are forgotten.

John Tenniel, "The Lobster," from Alice's Advendures in Wonderland (1865), by Lewis Carroll.

In this final image, we see a lobster admiring and primping himself in the mirror. This illustration accompanies another parody of a poem by Isaac Watts, "The Sluggard." In the original poem, Watts writes about a man who sleeps for the majority of the day, has very few belongings, and begs for money as a result of never having been taught to "love working and reading." Alice tries to recite the original poem, this time to the Gryphon and Mock Turtle, and once again recites a nonsensical version instead. In the version she recalls, the sluggard is now a lobster! Alice and the other characters around her are extremely confused and alarmed at this absurd telling of a poem that they should know and take to heart. Throughout Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Tenniel's illustrations add to Carroll's whimsy and fun and make the foolishness of his poems even more apparent, almost as if to transport us into yet another world within an already ridiculous setting. In "The Lobster," Carroll once again deems his own nonsense poetry as incorrect when read in context of the story and reinforces the notion that children's literature must ultimately teach a lesson, even when the majority of the story itself is lighthearted and good natured.