Installation Explanation:

To display these three art pieces, I envision a sort of trapezoidal space with three walls. The left and right walls will be uneven with the center wall. The left wall will be tall and thin, while the right wall will be shorter and wider in relation to the center. Between the edges of the center wall and the two side walls are long, vertical windows extending from the floor to the ceiling. The space of the building in which the installation is held should then be facing either north or south. The direction of sunlight in the room should then shift from the left to the right and direct viewers’ focus to either the left wall, the right wall, or the center wall—creating a sort of “barrier” between the different pieces—depending on the time of their visit.

Hung upon the center wall will be Valadon’s Joy of Life. Presenting this piece directly in front of viewers when they enter the space positions the viewers to examine the painting first. The painting depicts a nude male figure looking at various nude female figures out in a wild and forested location. The male figure is viewing from a distance with their arms crossed while the female figures are all depicted in more natural, relaxed poses. The viewers might then identify themselves as being something akin to the male figure (museum guests tend to walk around with their arms crossed in a similar, analytical way) and are asked to examine both the individual piece and installation as a whole.

The left portion of Joy of Life contains a tall, dark, and somewhat twisted tree stretching up through the piece. The tree acts as another sort of transition, then, to what will be displayed on the left wall: Stuck’s Bacchanal. Bacchanal is the taller of the three paintings, and so is placed on the tall-thin left wall to accentuate its dimensions. The painting is also bordered by the depiction of two large pillars stretching from top to bottom. These pillars both mirror the “pillars” of light from the sun and the distinction of the painting’s subject from the rest.

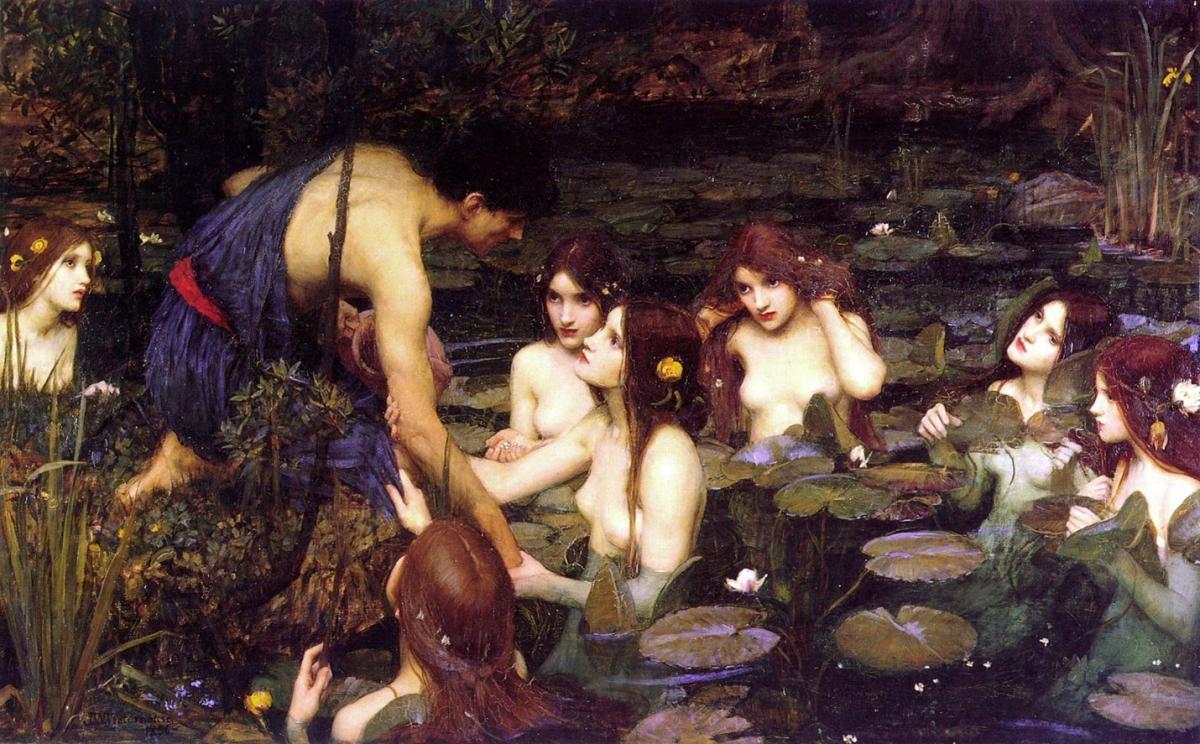

On the right of Joy of Life is the main male figure. Again, this enables a neat transition to the subject of the right wall: Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs. The title male figure in this painting, Hylas, is surrounded by a group of feminine appearing nymphs. The more compact wall space emphasizes how Hylas is being surrounded by having the painting take up more space. The barrier of light within the room also acts as greater emphasis of Hylas’ isolation.

Regardless of the order in which viewers go from the center to the surrounding walls, there is a clear indication that each display presents a different choice—giving viewers an individual sense of agency. How the individual chooses to examine the paintings, in which order and with what personal lens, is encouraged as being but one “path” or way of viewing both the installation itself and the themes of sexuality surrounding them.

Installation Note:

The main theme of this installation in one word is “choice”. Sexuality and sensuality are inescapable concepts which hold large sway over the average person. For those with a deep persuasion towards sexual desire or sensuality, it can be a force that speaks loudly. It can be mysterious, charming; aggressive, or consuming. What this installation presents, then, are pieces meant to evoke the various desires within the individual as well as indicate how their acceptance of the nature of desire can lead to different conclusions.

At the center of the installation is Valadon’s Joy of Life. The painting is quaint and charming, with earthy greens, browns, and yellows filling the scene. It is a natural setting. We see a man looking over at four different women—all of these individuals being nude, with the exception of a few women being partly covered with what appear to be towels. The man views from a distance, whilst the women go about their unknown business. Neither party directly interacts with the other, although it is unclear if the women are aware of the man’s presence. In the context of this installation, the man can be said to be deliberating on how to approach the women. In other words: how does the man choose to approach his sexuality? How do the women? It is a natural question, coming to the mind like the need to breathe, and one whose deliberation and answer should ideally bring joy.

The two other pieces, symbolically divided by beams of sunlight representing the focus of energy, show where sensual indulgency can lead to ravenous places. Remaining grounded within nature, Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs depicts a scene from the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts. The young man Hylas finds himself separated from the rest of the men and surrounded by multiple female water spirits, nymphs, who abduct him for his beauty: never to be seen again. The nymphs are mystical spirits who preside over various elements of the natural world—and, in art, represent these elements. Hylas is drawn in by the beauty of the spirits, and they too grow attached to him. It is their mutual allure for another that results in the feminine spirits submerging the young Hylas in their desire for him. The bright pale skin of the nymphs shines bright against the densely foliated pool around them—like light shining to rocky shores. Hylas and the Nymphs presents a cautionary story to the viewer on the power of nature. It is unescapable, mysterious, and utterly beautiful. When one approaches the sexual realm, they are filled with a compelling desire to dive deeper. It is not always dangerous, some versions have Hylas married to the nymphs, but it will swallow up the unprepared.

Opposite to Hylas and the Nymphs, left of Joy of Life, is Stuck’s Bacchanal. A bacchanal is a word deriving from the Greek god Dionysus, also known as Bacchus, god of wine and festivity. As a noun the word can refer to massive revelries or orgies. Stuck’s depiction of a bacchanal does not seem so explicit, however there are multiple men and women dancing around a fire. One nude man in particular reaches out to a naked woman, collapsed in the arms of another (possibly nude) man. It is a state of pure excitement. The atmosphere surrounding the people is greatly sinister. The only source of light is the fire in which they dance around; the smoke of which casts a ghastly shroud over their faces and forms what appears like a vaporous skull overhead. And in the background of this whole scene are the tops of trees: black and formless against the darkened sky. In the foreground, two pillars extending from top to bottom. Sexuality in the bacchanal form is no longer part of nature. It occupies a space between the structure of society and the untamed world only performed in darkness. Madness takes hold of the people and leaves them with nothing but the pleasure of themselves. An intoxicating, self-destructive revelry that forms the individual into a crazed mass.

The title of this installation is then The Nature of Eros. There is a profound joy found in love. Sex and sensuality come as a part of love’s nature, and can be as equally rich, beautiful, and wonderful as it is maddening, powerful, and mysterious. The individual must find their own joy after acknowledging the full nature of sexuality.

Image Sources:

Valadon, Suzanne. Joy of Life. 1911. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joy_of_Life_MET_DT356454.jpg.

Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

Waterhouse, John William. Hylas and the Nymphs. 1896. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waterhouse_Hylas_and_the_Nymphs_Manchester_Art_Gallery_1896.15.jpg. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

Stuck, Franz. Bacchanal. 1905. https://www.arthistoryproject.com/artists/franz-stuck/bacchanal/. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.