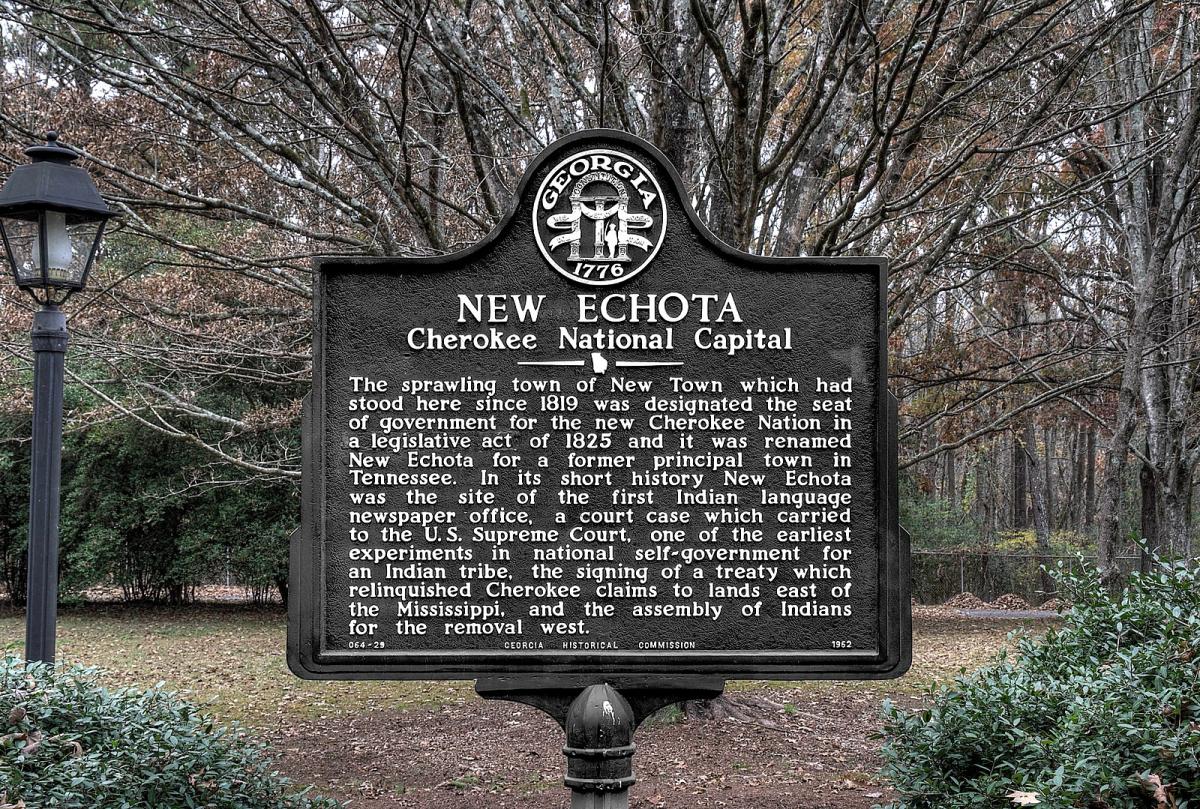

This crafted sign in New Echota, Georgia, is one of the typical history-recognizing and respected landmark signs scattered throughout the towns and street corners of the United States. What is significant, however, about this sign as it pertains to the context of this gallery is what the engraving tells the reader or visitor; it plainly informs the individual of the Cherokee’s losses and forced removal, but it also reminds one of the successes of the people’s post-Columbus attempts at independence. The Cherokee national legislature established the site of the sign, New Echota, as their new capital, the site of the first Indian language newspaper office, and one of the earliest attempts at Native American self-government before a treaty relinquished Cherokee claims to lands east of the Mississippi River and removed them westward on the Trail of Tears (New Echota State Historic Site). The given, textual context and the language of this carefully manmade sign speak volumes about the death of the old way of Native American life—in addition to the Cherokee way—before European settlement and the hard-fought rebirth of a smaller, honored, and unfortunately pitied collection of Native American groups within their own scattered reservations in America. Additionally, many of their stories, culture, and feats remain strong the American ethos today. Ultimately, this sign is an explicit symbol of the highs and lows of the long, fluctuating death and rebirth process of Native American preeminence and presence in this nation.

A Cherokee war song, translated by Henry Timberlake, written and spoken a century before the events described by the sign inscription, also reflect this death of a predominant nation of great tribes and the rebirth of scattered and small yet proud communities of people like the Cherokee. One part of the poetic song confesses, “But when we go, who knows which shall return, /When growing dangers rise with each new morn?” (Timberlake). There is a solemn acknowledgement by the song-composer and the Cherokee community from then that there is a strong chance, much as there had been before, that they will lose to the land-hungry invasion of European settlers as well as experience the death of their way of life abundant with people as much as it was abundant with freedom and diversity. Yet, the song also recognizes an everlasting victory for their nation: “And stain, with hostile streams, the conscious wood, /That pointing enemies may never tell/The boasted place where we, their victims, fell” (Timberlake). While the tribe may lose people and power, their victories in the form of trees and monuments listing the casualties of the battle will honor their legacies and forever inspire future, newly born generations to continue their way of life. On top of this, one author on Cherokee history notes that the Cherokee tribe refused to assimilate themselves with the American culture during the nineteenth century and instead readily made itself over in response to American society (Thornton 127).

Works Cited

“New Echota Historic Marker.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 30 Nov. 2019, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:19-35-135-echota.jpg.

“New Echota State Historic Site.” Official Georgia Tourism & Travel Website | Explore Georgia.Org, www.exploregeorgia.org/calhoun/general/historic-sites-trails-tours/new-….

Thornton, Russell. “Nineteenth-Century Cherokee History.” American Sociological Review, vol. 50, no. 1, 1985, pp. 124–27. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2095346.

Timberlake, Henry. “The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake….” The Project Gutenberg, 4 May 2021, www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/65256/pg65256-images.html.