Created by leah haveson on Tue, 10/15/2024 - 11:32

Description:

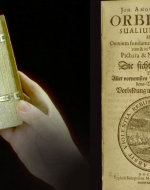

Tjebbe van Tijen & Milos Vojtechovsky, Orbus Pictus Revised; an Interactive Exhibition, 1996, Imaginary Museum.

This image is from an art exhibition that created a visual parallel to how Orbis Pictus functioned like the internet does, at a prototypical level. The artist created a learning station that acts like a more evolved version of orbus pictus, noting the "stool for children" labeled, it shows how the information is meant to accomodate the child, and allow them to learn. Orbis Pictus was full of thousands of definitions and illustrations, all compacted and readily accessible for young users. In a way, this text represents a landmark in the evolution of early education, as the majority of the internet is widely available to many children, now, when they started off with a picture book. Orbis Pictus exists as one book in a series of encyclopedias for children, full of definitions, latin, and most importantly illustrations. It has been printed in over 26 languages and over the last 3 centuries, over 200 editions have been published, and its contents cover a wide array of topics from “The Riches of the Earth” to “Social Behavior”. The tableaux in this book, like the art exhibit points out, are reminiscent of tabs on a computer screen, where many topics are all available. This text is an early landmark in children's literature, as one of the first children's books to prioritize illustrations as a guide for entertainment and learning. Comenius believed that people should continue learning their whole lives with the ultimate goal of peace, which was his primary goal, as a refugee of war and persecution. Within the study of literature, or any media studies, this book is a milestone in the development of distributing information, by making it accessible to children, similar to what this piece suggests.

Jürgen Ovens, Portret van Jan Amos Comenius, ca. 1650-70, Wikipedia. John Amos Comenius was born in 1592 in present day Czech Republic. His parents were members of the Protestant group Unitas Fratrum, but they died when he was ten as did two of his sisters. From a young age and throughout adulthood Comenius’s life was disrupted by religious conflicts, but pushed further into his faith. The church took him in as a young boy, but passionate orphan and funded a rigorous education. When he had finished his studies, he returned home and was ordained as a minister. Entertaining both the influence of Protestant Millennialism and science pioneered by those such as Francis Bacon, Comenius formed progressive views on religion, women, children, and overall education. He believed that science could help religion unfold. Comenius also believed that girls should be taught just as boys are. Further, unlike many of the time he believed that children should be taught with consideration to their individual needs and desires, with a focus on more material things than grammar. After the thirty years war began, he had to repeatedly leave his home and family to go into hiding, as he was a cleric of the Protestant church. During this time, his first wife and their children died, and then his second wife died as well, his house and library were also burned down. In 1628, Comemius and his third wife, his family, along with Unitas Fratrum fled to Lezno, Poland. From then until 1652, he poured himself into developing his theories on education. Following the Northern Wars in 1655, he was forced to abandon his work and life once more to go into hiding, where he died in exile in 1670 in Amsterdam. He developed a complex educational theory that influenced all of his works, notably Orbis Pictus which is regarded as the first picture book for teaching children. He believed that everyone, man or woman, should be holistically taught at all stages of life with the ultimate goal of creating a universal education. His phrase “theoria – praxis –chrésis” illuminates his overarching belief that without virtue and piety, or the protestant ideals of goodness he grew up with, knowledge is useless. The religious concept of praxis, the Greek work for practice, reflects Comenius’s values as he shows that he desires an education where knowledge is not idle, but in practice.

John Amos Comenius, Orbis Sensualium Pictus, 1658, Topipittori.

This image displays pages 4 and 5 of Orbis Pictus. On the left page, there is a list of small illustrations which depict various animals.There are two lines for each animal, which tell the reader what animal it is, and what sort of noise it makes. These descriptions are written in both Early Modern English and Latin. Alongside these descriptions are the English and Latin alphabet, to aid in translation. This page teaches vocabulary, alphabet, language, and common animals which are foundational elements of childhood education. Comenius believed that children should be taught in a way that was considerate of their learning style and not be purely focused on subjects like grammar. It follows, then, that the animals that Comenius chose to include on the page were animals that his average reader would be encountering. The illustration of the snake, interestingly, appears to have an arrow as a directional indicator. None of the other illustrations have this but it adds movement to the drawing. It would likely interest young readers, who hadn’t encountered a snake yet, how they move without legs.

The second page of the spread, on the right, has a poem, again in Early Middle English and the latin translation. There is an illustration above the poem which appears to depict flames of the sun, enveloping a pyramid connecting the Latin words: “Pater”, “Filus”, and “Spiritus”. This refers to the biblical trio of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Additionally, at the top of the page is “God” and the latin translation “Deus”. The poem itself tells the reader of God’s power and greatness. The last three lines read, “A Light inaccessible; and yet all in all. / Every where, and no where.” This is important in understanding Comenius’ proposed core elements of knowledge that children should universally know. Comenius introduces children to the sublimity and imperceptibility of God, by saying that God’s power and goodness is both everywhere and nowhere. This may be said with the intent to preemptively address any skepticism children may have of the intangible figure.