During the Victorian era in Europe, there was a modernist art theory known as Formalism. Formalism is described by Professors Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant as a rejection of “the non-aesthetic goals commonly assigned to art, such as imitation of nature, moral instruction, spiritual exaltation, and emotional expression” (Cramer and Grant, 2020), meaning the work should be experienced as a piece of art without any outside examination. Rather than observing art and applying it to current events, past events, or philosophies, the artwork is experienced within the four sides of the canvas. This movement was sparked by British Aestheticism, a movement coined by Oscar Wilde and other visual and literary artists. “Art for arts sake” was the motto. Their goal was to reject traditional conventions of art, such as capturing naturalistic forms, painting from life, illusionistic techniques, and emotional expression. When thinking about The Canterville Ghost, written within 10 years of the movement, it’s clear that Oscar Wilde himself was operating outside of a long-lived British tradition of writing and art. An example of his avant-garde style is in his collaboration with British artist Audrey Beardsley for his play Salome. A highly controversial play about seduction and Biblical characters, the illustrations by aesthetic artist Audrey Beardsley are abstracted from the conventions of Victorian illustration. Oscar Wilde’s choice to collaborate with artists who were part of British aestheticism mirrors his creative choices in The Canterville Ghost, which disrupts the conventions of British ghost stories.

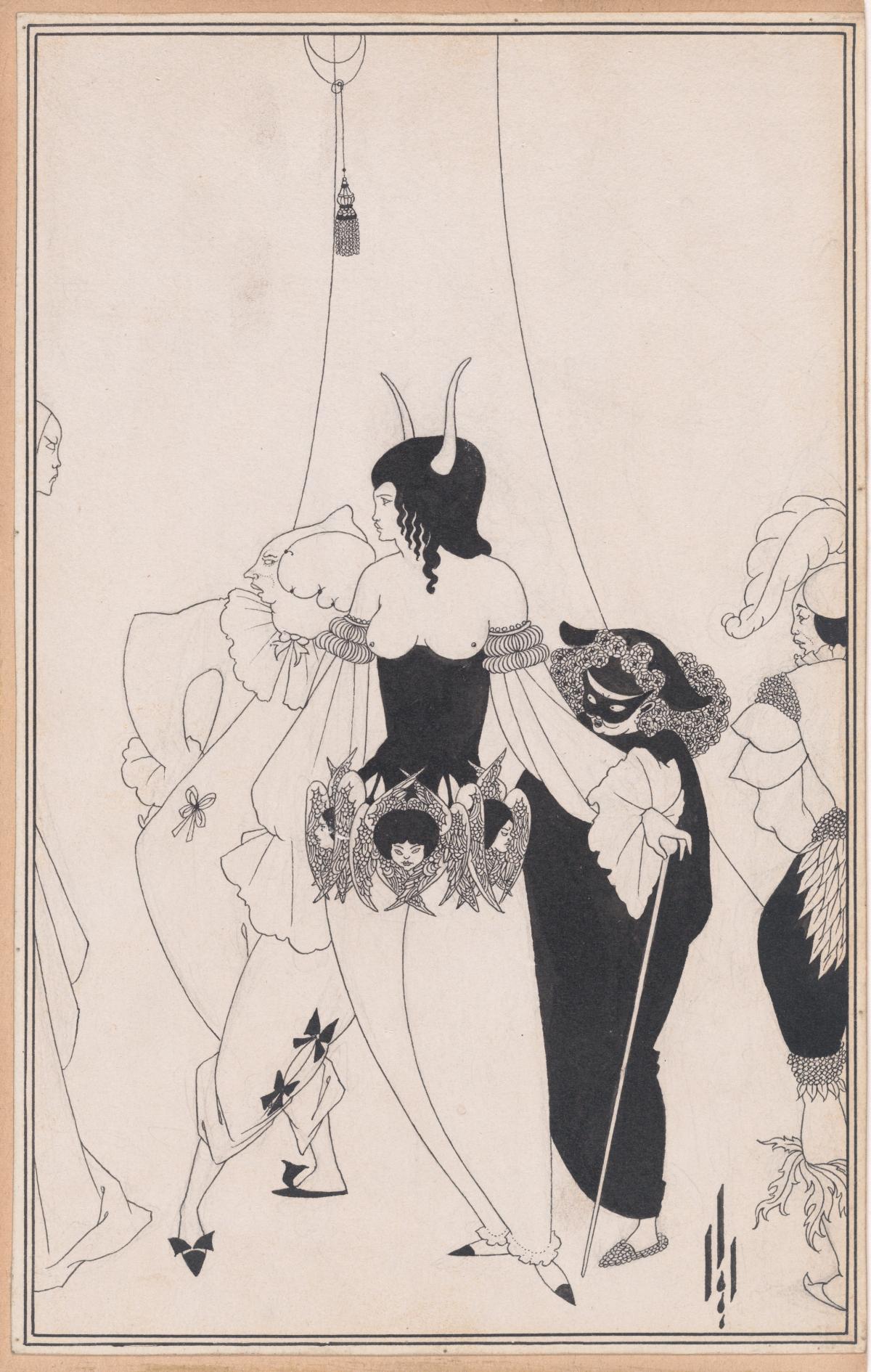

The first image pictured above is an illustration by Aubrey Beardsley known as The Masque of the Red Death, for Allan Edgar Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination, 1895-1896. Created during the same decade as Wilde’s Salome, the illustration has the same aesthetic qualities, such as geometrical shape, line, and black ink on white paper. Poe’s story is about a prince and his courtiers seeking refuge from the plague. The Met Museum describes the scene depicted as “Months of revelry culminate[d] in a masked ball, marked at midnight by the appearance of ‘a masked figure...tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head and toe in the habiliments of the grave’” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Compared to the second image, an example of an illustration within Victorian art conventions, Beardsley is clearly rejecting notions of proportions and illusionistic detail. The Execution of Lady Jane Grey at Tower Green by George Cruikshank creates an illusionistic space with a foreground and a receding background, giving the impression of depth, along with two-point perspective. Additionally, he treats the human form proportionately, making sure to be anatomically correct. Cruikshank respects the conventions of British Victorian art, whereas Beardsley’s piece is a complete rejection. The figures are flattened and disproportionate, rejecting illusionistic beauty that was valued in art.

Figure 1: The Museum of Metropolitan Art,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Aubrey Vincent Beardsley. “Aubrey Vincent Beardsley | The Masque of the Red Death, for Edgar Allan Poe’s “Tales of Mystery and the Imagination,” Chicago, 1895-96.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Figure 2: Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

Cruikshank, George. The Execution of Lady Jane Grey at Tower Green. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. 1840. victorianweb.org, https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/tol/1.html. Steel-engraving 13.3 cm high by 10.2 cm wide framed.