Created by Catherine Golden on Fri, 01/10/2025 - 11:33

Description:

Today we associate papier-mâché with elementary school art projects and Halloween costumes, but papier-mâché made a splash at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and impacted the fancy goods trade. In 1837, when Queen Victoria ascended the throne, there were approximately 25 manufacturers of papier-mâché in England. Papier-mâché is the French word for “chewed paper”; did the term arise because French workers in London papier-mâché shops chewed paper to make these goods, or is that just speculation? Nonetheless, as David Harris notes in Portable Writing Desks (2001), the Great Exhibition "marked the high point for papier maché" (34). A plethora of high-end papier-mâché items fill the pages of the Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue, some with accompanying illustrations. Manufacturers including Spiers & Son of Oxford offered a range of "Specimens of decorated papier mâché" including "tables, cabinets, fire and hand screens, albums, writing-portfolios, desks, envelope-cases, work-boxes, card-trays, panels for internal decorations, &c." Products made from papier-mâché typically have an ebony finish with designs composed of flowers, fruit, and birds with adornments in mother of pearl and gilding.

Despite papier-mâché's popularity, it fell out of fashion in the 1860s due to serial production. Notes Harris, “Excessive mass production led to a cheapening of items of all kinds and, as they were no longer quality pieces, they became less desirable" (30). Halbeard & Wellings (a Birmingham manufacturer) explains the two varieties of papier-mâché: "the best is produced by pasting together, on an iron or brass mould, a number of sheets of paper of a spongy texture, allowing them to dry between each addition. In the common variety, the paper is reduced to a pulpy substance, and the form is given by pressure into matrices of metal." The following case displays exclusively high quality papier-mâché goods inlaid with mother of pearl, gems, and floral designs to showcase a Victorian fashion trend in its heyday.

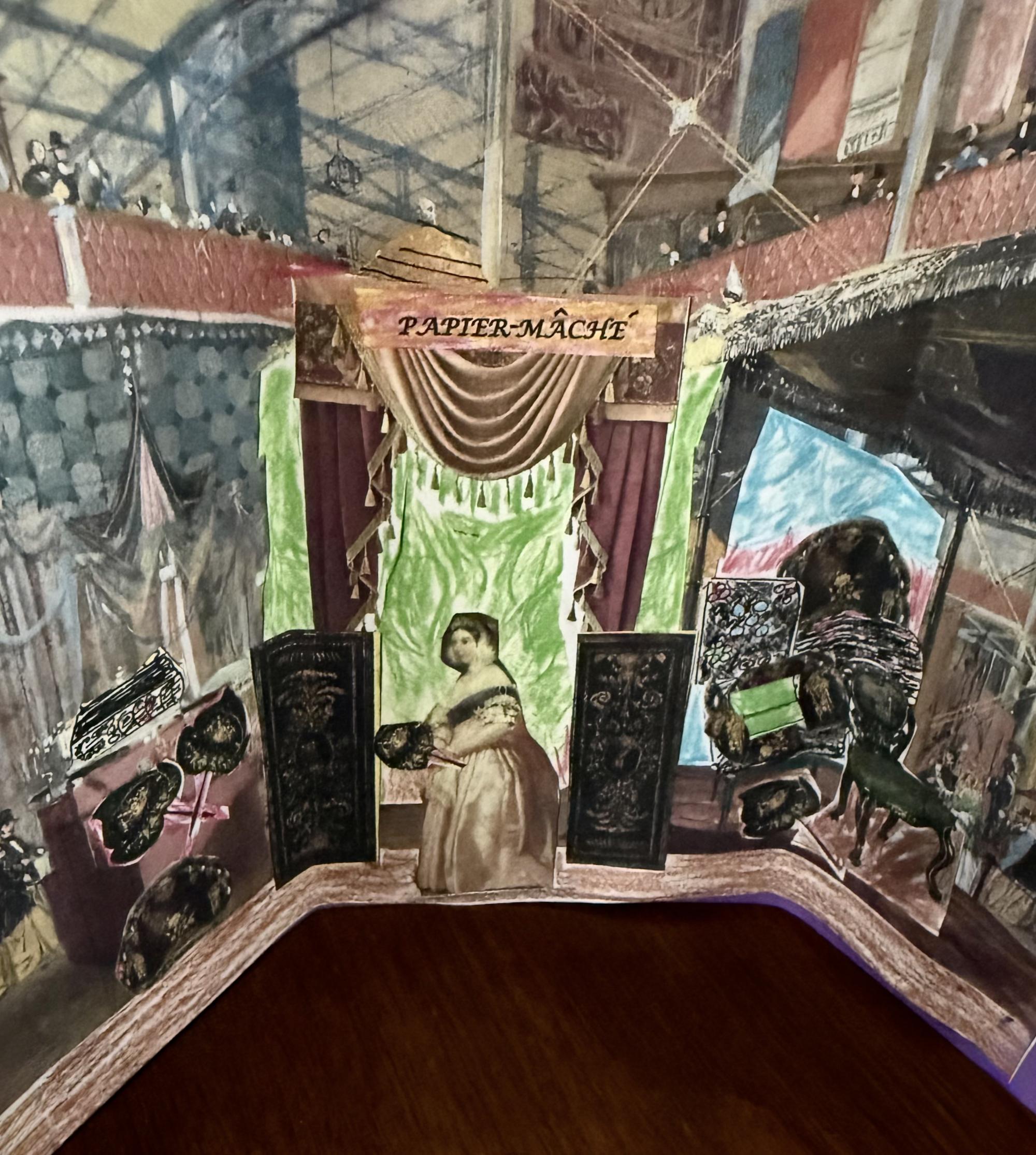

Booth for Papier-Mâché at our Great Exhibition of 1851, designed by Catherine J. Golden, 2025. This collage builds upon a drawing of the India display in the Great Exhibition of 1851 by Joseph Nash. Using it as a partial background, I created my own papier-mâché items and also added period images of fans, chairs, screens, and trays. The focal point is an image of Queen Victoria from a drawing of opening day of the exhibition (on Wikipedia) positioned between two large papier-mâché screens and holding a decorative papier-mâché fan. As you enter the booth, prepare to be dazzled!

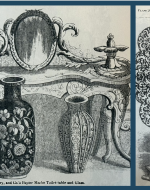

"Papier-Mâché Toilet Table and Glass" and "Papier-Mâché Chess-table," 1851, Clay, Henry, &Co., Covent Garden designers, in The Official Descriptive Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, Class 26, “Furniture, Upholstery, Paper Hangings, Papier Maché, and Japanned Goods” (volume 2, section 3), pp. 749-50. In their manufacturer's narrative, Clay, Henry, &Co. describe this toilet table and mirror as a "new design and principle, with chair and footstool en suite" (749). Two large vases of papier-mâché also form part of this grouping. The manufacturer, who directs the reader to both of these images, describes the object to the right of this paired image as "A chess-table in papier-mâché, the centre of glass, enamelled with mother-of-pearl" (749). All this company's items are of high grade papier-mâché.

Papier-Mâché Portfolio Embellished with Mother of Pearl, ca. 1860, from the Personal Collection of Catherine J. Golden. This portfolio designed to hold writing paper has an exquisite design. A floral centerpiece is framed by a circular and rectangular pattern composed of shimmery mother of pearl with gold embellishments. Victorian material objects —in their size, materials, and degree of decoration—speak to the social class and gender of their owners. The degree of ornamentation on this fancy good suggests its owner was a genteel lady of the upper reaches.

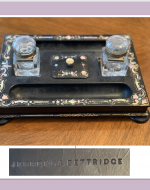

Papier-Mâché Desk Set Inlaid with Mother of Pearl by Jennens & Bettridge, ca. 1850s, from the Personal Collection of Catherine J. Golden. In business from 1815 to 1864, Jennens & Bettride earned a reputation as "makers of best-quality British papier mâché, and articles made by them were generally marked with their name" (Harris 33). As evidenced in this desk set, ornamentation with mother of pearl was a particular specialty of this manufacturer, known as "Makers to the Queen." This leading Birmingham designer made two grades of papier-mâché as evidenced by this line in their manufacturers’ narrative that reads: "Four tea-trays, exhibited for their cheapness, being of the second quality papier maché (or 'pulp')." An illuminating parenthetical remark follows this entry: "There are two modes of manufacturing 'papier maché' articles: the first is by pasting paper in sheets upon models, and the second by pressing in dies, the pulp of paper. The former produces the best quality, and the latter the least expensive and inferior kinds. The specimens above-named as 'exhibited for their cheapness,' are of the latter description, and the rest are of the former." This desk set contains two glass inkwells with ornamented with brass lids, pen holders on both sides of the base, and a center compartment to hold small items including sealing wax. The bottom of the desk set, shown in this image, bears the famous company's name.

Lady's Papier-Mâché Writing Desk, ca. 1850s, from the Personal Collection of Catherine J. Golden. Writing desks — which we might aptly call Victorian laptops — came within economic reach of the increasingly literate Victorian middle class by the 1830s. The Victorian age produced more writing desks than any other for a combination of reasons: developments in the fancy goods trade, a rise in literacy, and the coming of the Penny Post in 1840, which, in turn, increased the number of post offices and decreased the cost of postage; a letter weighing up to ½ ounce could travel anywhere in the UK for only a penny. Victorians relied on their writing desks for correspondence, and the Great Exhibition, which showcased papier-mâché writing desks, increased middle-class demand for them. A lady's desk was smaller than one designed for a gentleman and boasted a greater degree of ornamentation. The outside of this desk has a floral pattern and mother of pearl inlay. It opens to reveal a purple velvet writing slope. This item of furniture has storage for writing materials, a pen tray, one inkwell, and a stamp tray, confirming this desk was manufactured after 1840 when Britain introduced the first postage stamp, the Penny Black. This desk resembles those on display in Class 26, “Furniture, Upholstery, Paper Hangings, Papier Maché, and Japanned Goods” (volume 2, section 3) from The Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Papier-Mâché Tea Box, ca. 1850s, from the personal collection of Catherine J. Golden. By the 1800s, only beer (ale) rivaled tea in popularity. Tea was a beverage of choice among all social classes since the water was boiled, making it safe to drink (unlike beverages made from un-boiled water). In England, people kept tea in locked boxes, also called tea caddies, because tea was so costly. Since import duties kept the tax on tea high, savvy merchandisers created tea recycling factories—there were 8 in London in 1840—and manufacturers mixed old tea leaves and new for resale. In fact, used tea leaves were called “cha,” and the expression “char lady” designated the person who would take away the used tea leaves to recycle them. By the 1860s, afternoon tea was a well established Victorian ritual. Caddies, first made of Chinese porcelain and often patterned in blue and white, were shaped like canisters and had stoppers. By the nineteenth century in England, the shape of the tea caddy changed from a canister to a casket and was made from quality woods like rosewood, mahogany, and satin-wood as well as papier-mâché, as in this case on display. The outside of this tea box has mother of pearl decoration, and the casket sits on gilded feet. Inside we find two receptacles for different types of tea. The receptacles are lined with tin to keep the tea leaves fresh and have ivory knobs. Like all Victorian tea caddies, this tea box also has a lid and a key lock. Today, we still take precautions to lock away our valuables although tea is not typically one of them.

Papier-Mâché Cabinet, circa 1850, Ebonized and Inlaid with Mother of Pearl, Decorated with Gilt and Sprays of Polychrome Flowers, from the Collection of Dame Nellie Melba GBE, Carter's Price Guide to Antiques. This cabinet has a domed rectangular top, which, when opened, reveals a segmented compartment for jewelry that is lined in silk. The doors, when opened, show eight drawers and a central pigeonhole. The cabinet sits on four bracket feet. This item of furniture resembles those on display at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Papier-mâché goods, originally small decorative items--trays, snuff boxes, letter holders--increasingly expanded to writing desks, tea boxes, and eventually to larger items of furniture including fire screens, wardrobes, and cabinets, as this case demonstrates.