People of color held an influential role in the era of freakshows. Though physical abnormalities and fantastical abilities were still enjoyed by the audience, what really thrilled them was the sight of foreign bodies on stage. Oftentimes, the only oddity that these immigrants held was their ethnicity, yet this made them strange enough for British and American audiences to be amazed. Ethnocentrism ran rampant through Western society, especially concerning who they deemed as socially acceptable. Simply being a person of color qualified many immigrants to be placed on stage, reduced to derogatory and racially-charged names or antics. Sometimes, like in the case of Sarah Baartman, the ‘deformity’ was only that of her natural African figure, which was seen as vulgar when compared to the average European woman. For others, like Hassan Ali, his taller-than-average height made him the Egyptian exile amongst British gentlemen. It becomes apparent that freakshows relied on exploiting POC features and traits in order to impress white audiences. From equating African persons to monkeys, to claiming that a Salvadoran pair of children were savages found in the jungles, the blatant racism that ensued was undeniably intertwined into the heart of freakshows. Dehumanization and harassment were just the beginning of the torment that many people of color faced while working in freakshows, as many faced tragic ends at the hands of their oppression. For some, their exploitation continued even in death, as their bodies were pickled and kept on display until the late 1980s. Even today, insensitive callbacks to POC in this era can still be noted. Ultimately, the maltreatment of persons of color has a long history, and even lives on today. The most respectful way to address their hardships is to note that the only thing society truly considered abnormal was the thing they were born into: their ethnicity.

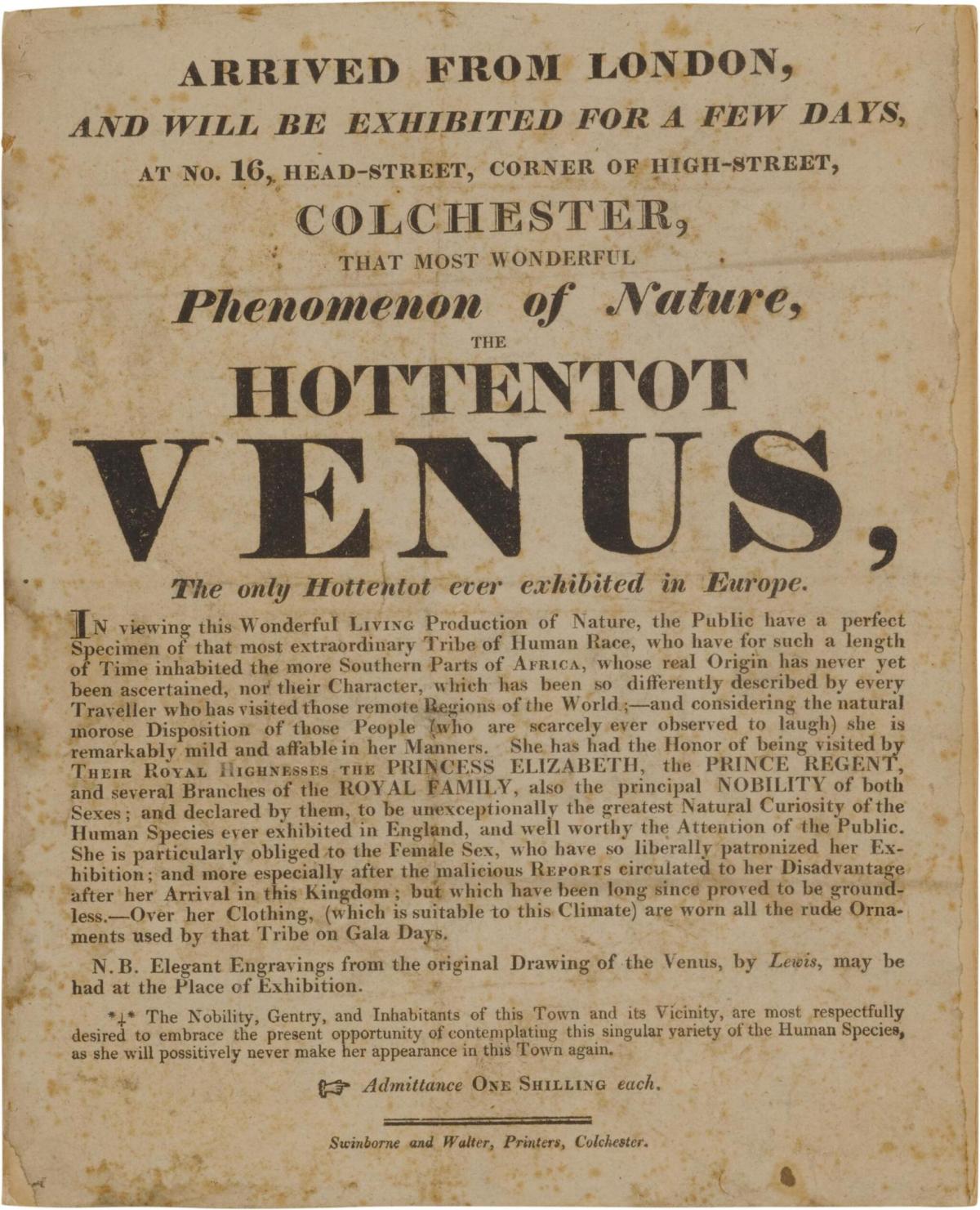

Artifact One: (1810) Advertisement for the Exhibition of Saartjie Baartman

Parkinson, Justin. “The significance of Sarah Baartman.” BBC, 7 January 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35240987. Accessed 22 April 2022.

One of the earlier examples of the inclusion of persons of color in freakshows is the case of Saartjie, or ‘Sarah’, Baartman. Baartman was showcased across Europe as a freakshow attraction due to her curvaceous figure. Given the stage name ‘Hottentot Venus’ for her provocative body, Baartman wore skin-tight, flesh-colored clothing on stage, with beads and feathers decorating her as a reference to her African -specifically Khoikhoi- heritage. She would smoke a pipe as she performed, and wealthy customers could pay for private demonstrations in their homes, where they were even allowed to touch her. Baartman was fetishized and demonized for her natural figure, being exhibited in animal enclosures in France where she would be forced to show her body with barely any covering on. She was even studied by French anatomists, zoologists, and physiologists, as they argued that Baartman was a “link between the human race and animals.” Her mistreatment continued past her untimely death at the age of 26, as her body was dissected by a French scientist who then pickled her brains, buttocks, and genitalia for display in jars at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, where they remained on view until 1974. Some recent controversy surrounding her continued fetishization concerns a photograph of Kim Kardashian mimicking a pose Baartman was drawn in, pouring champagne into a glass balanced on her large buttocks. This image caused outrage as critics recalled how horribly Baartman was treated for her figure, only to now have it be romanticized and replicated by privileged non-POC celebrities.

Artifact Two: (1855) Ticket for the Aztecs and the Earthmen

“[Illustrated 'favour ticket' to an exhibition of Aztec Lilliputians from Iximaya in central America and the Erdmanniges from under the earth in South Africa. Possibly 1855].” Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/jabunhkz/items. Accessed 22 April 2022.

The following example of persons of color being included in freakshows is that of the ‘Aztecs and Earthmen.’ These people were offensively misnamed so as to sensationalize their foreignness, as they were usually simply Latin-American and African people who were sold to the shows by kidnappers. This illustrated ticket to an exhibition of ‘Aztec Lilliputians’ from Iximaya in Central America and the ‘Erdmanniges from under the earth’ in South Africa serves as a prime example of how freakshows often highlighted different cultures as a marketable oddity. Oftentimes, these people had no physical or mental disabilities, with their only impairment being a social one: not being a white European. The clipping introduces them as “A new race of people found in the unexplored regions of Central America…A race of people who burrow under the Earth, from South Africa, the first-ever captured alive. Neither the Aztecs or the Earthmen have any language.” Not only does this tagline exaggerate the extent of their civility, painting them as ‘savages’ who were newly discovered and lacked any class or intelligence, but it also feeds into the negative stereotypes surrounding persons of color in this era. By describing Latin-Americans and Africans as “Two new races of people, the first of either race ever discovered… unlike any human beings ever before seen,” audience members were given the misguided notion that these people of color were inherently below them due to not being fully human. Freakshows often attributed animalistic traits to minority cast members, thus isolating them even more from society- even if they weren’t a freak for any other reason.

Artifact Three: (1876) Ticket for The Aztecs, Máximo and Bartola

“[Undated (1876?) illustrated handbill advertising an exhibition of Maximo and Bartola, the Aztec Lilliputians from Iximaya in central America].” Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/fwck3xw8. Accessed 22 April 2022.

Just as the concept of ‘Aztec Lilliputians’ was sensationalized in the past, they continued to be well into the 1870s. This illustrated handbill advertising an exhibition of Máximo and Bartola. two Salvadoran siblings both suffering from microcephaly and cognitive developmental disability. They were exhibited in human zoos in the 19th century, eventually billed as ‘Aztec Children’ alongside a farcical story of how they were found in the temple of a lost Mesoamerican city by the name of Iximaya. Máximo and Bartola toured the U.S. and Europe, with their advertisements claiming that they were the “only Aztecs yet introduced to civilized white people.” Even though taglines of Aztecs being a ‘newly discovered race’ floated around for an entire century, these claims of being the first to see these foreigners drew in many show-goers across Europe and the states. Máximo and Bartola had a publicly staged wedding in 1867 in an attempt to garner more publicity and attention, even though they were blood-related siblings. The concept of incest in regard to tribal people was a particular topic of interest for white society, contributing to the less-than-civilized view that they had towards foreigners and different cultures. Máximo and Bartola faced constant dehumanization and harassment, as freakshow advertisements described them as “totally unlike anything deemed human- their heads being formed like the head of an eagle- their hair growing erect on their head…” and ultimately exclaiming: “They were formerly used by the Mayaboon Indians as living idols!” Native people were also mocked incessantly in freakshows, as their beliefs were considered a marker of uncivilized people.

Artifact Four: (1895) Poster advertising The Egyptian Giant

“London Pavilion : the Egyptian Giant : every evening.” Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/bn5jfwtk. Accessed 22 April 2022.

The following artifact is a poster advertising the appearance of Hassan Ali, or ‘The Egyptian Giant’, at the London Pavilion in Piccadilly, in 1895. Ali was known for his 8-foot-2 stature, as he towered over the average man across all of Europe. The image on the poster shows Ali in Middle-Eastern attire, with his left arm outstretched over the head of a British gentleman sporting a top hat, dark suit, and a mustache. This visual juxtaposition highlights the difference between freaks and ‘civilized’ people, creating an easily-noted disparity between which one seemed more respectable. Ali’s height and style of dress isolated him from British society because of its foreignness. The sphinx and pyramids in the background also add to the sensationalizing of other cultures, as show-goers were usually enticed by promises of getting a glimpse into ‘strange, foreign lands.’ The irony here is that the show itself was taking place in London, so the inclusion of Egyptian landmarks was only meant as a mockery of Ali’s ethnicity rather than a preview of the show itself. Ali remained an outcast in society due to his noticeable height, with a New York Times issue in 1901 reading: “A GIANT'S HIDDEN CIGARETTEs; Customs Officials Say There Was a False Bottom in Ali's Trunk.” The article went on to read: “Hassan Ali of Cairo, Egypt, a young man who towers eight feet two inches, landed on American shores from the Italian liner Nord Amerika yesterday morning. When Hassan's trunk was searched by the customs officers for dutiable articles, they found in the bottom, which the customs people assert was a false one, 2,000 cigarettes.” The fact that he was singled out and searched, and that his height remains the defining feature of the article, highlights how Ali was always viewed as an ‘other.’

Artifact Five: (1915) Photograph of Ota Benga

Howard, Mikelle. “Ota Benga (1883-1916).” Blackpast, 22 September 2018, https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/benga-ota-1883-1916/. Accessed 22 April 2022.

The final artifact is a portrait of Ota Benga in the Bronx Zoo, who was photographed alongside a monkey as part of his attraction. Ota Benga was a Congolese pygmy man whose wife and children had been murdered by the Force Publique, a militia group established by King Leopold II of Belgium to control the natives in Congo. Shortly after the murder of his wife and children in 1904, Ota was captured by slave traders and sold to Samuel Phillips, an American businessman, and explorer; Samuel purchased Ota from slave traders for a pound of salt and bolt cloth, but was set to experience huge monetary gains from exploiting Ota in the states. Samuel made a fortune by exhibiting Ota in various human zoos, as well as in The Saint Louis World Fair, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Bronx Zoo. Ota’s oddity, alongside his race in general, was his peculiar look. Being a short dark-skinned man with sharpened teeth made him a hit at the zoo. At the Bronx Zoo, Ota was showcased as part of the monkey exhibit, illustrating the Victorian era’s obsession with likening black people to apes. This racially-charged mindset contributed to the mistreatment Ota faced, as he was often harassed by audience members and highlighted with offensive terminology in the newspaper. Ota’s life ended in tragedy as he shot himself in the heart on March 20th, 1916, at the age of 32. Before doing so, he built a ceremonial fire and chipped off the caps on his teeth, reclaiming his body by preventing them from keeping his teeth after his death. Ota knew that scientists would try to exploit him, even in death, as they had done to many people of color in freakshows in the past.

In the end, people of color were exceedingly targeted and exploited by freakshow culture. One major detail that can be noted is how advertisements regarding POC and immigrants in freakshows morphed over time, going from text-based posters bolding their ethnicities, to visual posters with drawings of cultural objects, to pictures of the person themselves being equated to animals. By addressing the unfairness of how minorities were treated in the 19th and 20th centuries, society can move forward into the future with more respectful attitudes toward the beauty of the bodies of all people from all cultures and races.