Introduction

While Victorian literature frequently employs the concept of “narrative prosthesis” to manage representations of disability, often through mechanisms resembling material or technological extensions aimed at restoring a sense of bodily "wholeness" (Hingston 370), a close examination of Dinah Maria Mulock Craik's work, The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak, reveals a more complex engagement.

Through this, it is clear that these “prostheses,” including magical gifts that function as artificial replacements or enhancements (Mitchell and Snyder 48), simultaneously function to normalize disability within the plot structure (Hingston 371) while narrative perspective subverts such normalization by emphasizing the social dimensions and pervasive nature of difference (Mitchell and Snyder 48), ultimately reflecting the complicated and ever-changing role of the body in Victorian thought (Hingston 370) and contributing to a broader understanding of care and relationality surrounding disabled figures in her narratives (Miller 5).

The following images expand upon these ideas, ranging from illustrations included in the original work, images inspired by the original work, as well as historical objects that can contextualize the role of prosthetics in the perception and treatment of individuals with disabilities throughout history.

Works Cited

Almond, Gemma. “Normalizing Vision: The Representation and Use of Spectacles and Eyeglasses in Victorian Britain.” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 26, no. 2, 2021, pp. 267-281. https://doi.org/10.1093/jvcult/vcab007

“Concealed Hearing Devices of the 19th Century.” Legacy Exhibit, Washington University School of Medicine/Bernard Becker Medical Library, 2009. https://beckerexhibits.wustl.edu/legacy-exhibits/did/19thcent/spv.htm#:~:text=At%20the%20turn%20of%20the,or%20worn%20on%20the%20person.

Coolidge, Susan. What Katy Did. Boston, Roberts Brothers, 1872.

Craik, Dinah Maria Mulock. The Little Lame Prince and His Traveling Cloak: A Parable for Old and Young. Illustrated by Dorothy Bayley, 1900. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_little_lame_prince_and_his_traveling_cloak_-_a_parable_for_old_and_young_%281900%29_%2814577025870%29.jpg.

Craik, Dinah Maria Mulock. The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak. Illustrated by Warwick Goble, Project Gutenberg, 2007. www.mirrorservice.org/sites/ftp.ibiblio.org/pub/docs/books/gutenberg/2/4/0/5/24053/24053-h/images/illus-027l.jpg.

Craik, Dinah Maria Mulock. The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak. London, Daldy, Isbister & Co., 1874.

Hingston, Kylee-Anne. “PROSTHESES AND NARRATIVE PERSPECTIVE IN DINAH MULOCK CRAIK’S THE LITTLE LAME PRINCE.” Women’s Writing, vol. 20, no. 3, 2013, pp. 370–386. https://doi-org.ledproxy2.uwindsor.ca/10.1080/09699082.2013.801125

Miller, Theresa. “Rethinking Care: Disability and Care in Dinah Mulock Craik’s ‘The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak.’” Limina: A Journal of Historical and Cultural Studies, vol. 21, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1–11. https://doaj.org/article/24b4165a18244d86b6b1e5ac3715b09c

Mitchell, David T., and Snyder, Sharon L. Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse, University of Michigan Press, 2000.

Mitelli, Giuseppe Maria. “Bugia peste e cagion d'ogni gran male.” The British Museum, pp. 1680-1710. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1852-0612-531.

Mitelli, Giuseppe Maria. “Schoenenverkoper.” Rijksmuseum, 1660. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/object/Schoenenverkoper--41e7ea918be0d76cd131334bcd0bb7d9

Ralston, John McLaren. The Little Lame Prince, 1874 https://www.nineteenthcenturydisability.org/items/show/14

Science Museum Group Collection. Pair of Wooden Crutches, 1901-1920. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co127160/pair-of-wooden-crutches-1901-1920

SSPL/London Science Museum Dunscombe collection. “A Pair of Rimless Eyeglasses/object number 1921-323/375.” “Normalizing Vision: The Representation and Use of Spectacles and Eyeglasses in Victorian Britain.” Gemma Almond, Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 26, no. 2, 2021, pp. 267-281. https://doi.org/10.1093/jvcult/vcab007

“Trumpet Headband.” Legacy Exhibit, Washington University School of Medicine/Bernard Becker Medical Library, 2009. https://beckerexhibits.wustl.edu/legacy-exhibits/did/19thcent/spv.htm#:~:text=At%20the%20turn%20of%20the,or%20worn%20on%20the%20person.

Winthrop, Peirce, H. The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak: A Parable for Young and Old. 1893. https://www.yesterdaysmuse.com/pages/books/2342777/miss-mulock-dinah-maria-mulock-craik/the-little-lame-prince-and-his-travelling-cloak-a-parable-for-young-and-old

Images in the Series

Fig. 1. Ralston, John McLaren. The Little Lame Prince. 1874 https://www.nineteenthcenturydisability.org/items/show/14

In this image, Prince Dolor is lifting off through the ceiling on his cloak—his face full of hope and wonder. He cannot walk, but this cloak gives him something his body can’t: the power to move and to explore. It is more than just magic for him; it fills the gap where his legs are. This is similar to how some people today rely on things that help them move (such as crutches), giving them a way to live on their terms. The cloak becomes a stand-in for what we now call prosthetics—not just tools, but a connection to the world beyond the room.

The cloak feels a lot like modern devices, for example, wheelchairs and prostheses. It provides him with independence rather than merely aiding in his mobility. It is giving him a chance to survive, not just simply changing him or making him “normal.” Prosthetics have become a part of people’s perceptions of the world and are more than just tools.

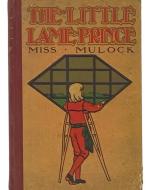

Fig. 2. Winthrop, Peirce, H. The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak: A Parable for Young and Old. 1893. https://www.yesterdaysmuse.com/pages/books/2342777/miss-mulock-dinah-maria-mulock-craik/the-little-lame-prince-and-his-travelling-cloak-a-parable-for-young-and-old

Prince Dolor is shown with crutches on the cover of this version of The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak, gazing out of a window shaped like a diamond. He appears to be completely concentrated on whatever is outside because his back is turned and his body leans forward slightly. In addition to clearly indicating that he has a disability, the crutches also convey his attempt to remain upright and involved in society despite his physical limitations. He is standing, inquisitive, and curious even if it is only through a window, instead of lying down.

The crutches seem to be similar to modern prosthetics. Supporting someone’s freedom and dignity is more important to them than simply helping them walk. Even though he is not playing or running, Prince Dolor is still morally pure and interacting with the outside world as best as he can; that is important. It demonstrates resiliency rather than weakness. He is making an effort to remain present and engaged despite the limitations imposed by his body. The simple act of standing there conveys a lot about the mental and physical navigation of the environment by people with disabilities. The level of care and empathy with which a children’s book from so long ago depicts disability is somewhat shocking.

Fig. 3. Mitelli, Giuseppe Maria. “Schoenenverkoper.” Rijksmuseum, 1660. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/object/Schoenenverkoper--41e7ea918be0d76cd131334bcd0bb7d9

Giuseppe Maria Mitelli was a prominent etcher, painter, and sculptor, with his work often depicting ceremonies, pageants, warfare, folklore, trades, and religious objects, providing a glimpse into Bolognese life. In this piece, “Schoenenverkoper,” translating to “Shoe Seller” in Dutch, Mitelli depicts the life of a shoe seller in 17th century Italy, a man marked by his economic circumstances, with his bare foot and simple attire portraying a life of manual labour. Mitelli's piece invites us to consider the lives of those who lived on the margins of society, and the cultural values we place on labour, class, and ability. While this piece focuses on economic marginalization and labour, and The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak centers on physical disability, both works engage with the broader theme of representing individuals on the margins of society. They invite reflection on the dignity and humanity of those deemed “different” and prompt consideration of societal attitudes towards them. Mitelli's shoe seller is marginalized due to his economic class, shown by his bare foot and simple clothes, which also indicates manual labour. Similarly, Prince Dolor is marginalized due to his physical disability and isolation in a tower. Both works bring to the forefront individuals often underrepresented in mainstream societal depictions. This act of making a marginalized group visible aligns with disability studies' aim to highlight the experiences of underrepresented disabled individuals. Furthermore, the shoe seller's shoes, the tools of his trade and markers of his economic status, can be conceptually linked to Prince Dolor's magical gifts, which act as literal prostheses. For Prince Dolor, these initially emphasize his difference while enhancing his abilities, whereas for the shoe seller, his wares define his livelihood and marginalization. Both depictions illustrate the social consequences of being defined as different, whether through disability or economic status.

Fig. 4. Mitelli, Giuseppe Maria. “Bugia peste e cagion d'ogni gran male.” The British Museum, pp. 1680-1710. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1852-0612-531.

In this piece, Giuseppe Maria Mitelli creates an allegorical figure of Lying, depicting a woman pretending to have a disability. One knee is supported by a crutch, her hair, clothes, and overall appearance portray the physical manifestation of lying, and the burning straw is used to represent the lack of substance in her words, with the wooden leg representing the little stability she has. By utilizing a visual trope of disability and associating feigned disability with deceit and negativity, Mitelli inadvertently perpetuates harmful societal attitudes. This depiction can be compared to The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak, particularly through the lens of disability as a narrative device and the complexities surrounding its representation. In Mitelli’s piece, disability is not a genuine deviance to be overcome, but is a fabricated one used for deceptive purposes. This could be seen as a reverse form of narrative prosthesis, where the appearance of a “lack” is used to create a desired narrative that is ultimately false. While the overall structure in The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak might seem to remove disability by prostheticizing it through magical gifts, the narration and focalization actually destabilizes the idea of a “normal” body. The allegory, in contrast, reinforces a simplistic understanding of disability as something that can be easily faked and exploited. The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak also draws the reader's attention to the social, rather than the physical, experience(s) of disability. Prince Dolor's suffering is shown to stem more from the social consequences of having a body defined as different than from the physical limitations themselves. The allegory of Lying, by depicting someone feigning disability, plays on societal assumptions and pity associated with physical impairment for dishonest gain. This highlights the power of social perception and how the appearance of disability can be manipulated. However, The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak, through focalization on Dolor, aims to foster empathy for the social realities of disability, while Mitelli uses the performance of disability to evoke pity for manipulative ends.

Fig. 5. SSPL/London Science Museum Dunscombe collection. “A Pair of Rimless Eyeglasses/object number 1921-323/375.” “Normalizing Vision: The Representation and Use of Spectacles and Eyeglasses in Victorian Britain.” Gemma Almond, Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 26, no. 2, 2021, pp. 267-281. https://doi.org/10.1093/jvcult/vcab007

Prosthetics are artificial devices typically used to replace absent body parts and/or an absent/diminished bodily function, or at least help in assisting/correcting the use of a missing/diminished bodily function, whether congenital or as a result of trauma or sickness. People typically view prosthetics as removeable artificial limbs or appendages, but even more simple objects such as glasses or hearing aids are known as prosthetic devices.

Within the Victorian period, spectacle and eyeglass use became more widespread (Almond 268). The glasses in this particular image are known as rimless frames, invented between the years 1825-1840, although at the time, they would have been marketed or described as “invisible” (Almond 269). The rimless, or invisible, glasses were created with the intent to conceal, as many people desired discreetness and the ability to “hide their defect,” since visual aids as assistive devices were still subject to forms of stigma, as they drew attention to the “abnormality of vision” in individuals, therefore indicating that person was outside societal norms or standards (Almond 276). This is interesting in the connotations it has to the medical model of disability, with the notion of “curing” abnormalities and catering to the idea that disability, especially visible disability, is “wrong.” Although it is true that prosthetics do not cure, in the sense of getting rid of a disability altogether, they do function to “fix” so-called defects and help “normalize” an individual, rather than changing or fixing the surrounding environment to make it more accessible. Other forms of glasses at the time include those made with steel frames or handfolders, which could be made more decorative with carved designs (which still did not indicate acceptance or a wish to show off, but the hope to mask) (Almond 271).

Glasses, as a form of (visual) prosthesis, is important when it comes to The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak because Prince Dolor receives a “pair of the prettiest gold spectacles ever seen” (Craik 61) by his godmother, which allow him to “see every minute blade of grass, every tiny bud and flower (…), even the insects that walked over them” (Craik 60). Prince Dolor even claims to “have as good as two pairs of eyes” (Craik 71) when using his glasses. Prince Dolor is not at all blind himself in the story or even seeing impaired, however, as he has been forced into isolation, as a result of his existing disability, his spectacles act almost like binoculars, bringing him somewhat closer to seeing and interacting with his society/environment. It brings a sense of independence and freedom. This idea is, therefore, similar to what glasses would do for those within the Victorian period (and even today) – provide people a way to help correct or augment their vision in order to feel a part of/see within a society not catered to blind/seeing impaired people, especially during a time that valued functionality, labour, and ability.

Fig. 6. “Trumpet Headband.” Legacy Exhibit, Washington University School of Medicine/Bernard Becker Medical Library, 2009. https://beckerexhibits.wustl.edu/legacy-exhibits/did/19thcent/spv.htm#:~:text=At%20the%20turn%20of%20the,or%20worn%20on%20the%20person.

Today, hearing aids and cochlear implants are considered auditory prosthetic devices. Therefore, the object in this image is what was known as a Trumpet Headband, an early form of the modern hearing aid. Despite looking rather bulky itself, the Trumpet Headband actually evolved from much more cumbersome and noticeable ear trumpets, which required the individual to hold up to their ear and included long speaking tubes (“Concealed Hearing Devices”), which did not make useful for everyday use. The Trumpet Headband, in comparison, was designed with more every day, ease of use in mind, as the intent was to wear the band over your head or around your neck and could be concealed/blend in with a hat or hairstyle (“Concealed Hearing Devices”). This ability to conceal, a new design trend for assistive devices at the time, might have “encouraged more users to wear hearing devices” since they were more aesthetically, “cosmetically [and/or] socially acceptable for public use” (“Concealed Hearing Devices”); however backwards the reasoning, this did help increase accessibility for d/Deaf or hard of hearing individuals. Acoustic headbands, an overarching title which includes the Trumpet headband, were invented by F.C. Rein in 1802 (although this Trumpet Headband was specifically created in 1850) and were first known as Aurolese Phones; they are the “earliest known design of a concealed hearing device” (“Concealed Hearing Devices”). From this invention delved other concealed auditory assistive devices, such as acoustic fans for women, acoustic chairs, and even the water canteen receptor and beard receptacle (“Concealed Hearing Devices”).

Within the The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak, Prince Dolor is given “a pair of silver ears” (Craik 71) by his godmother, which fit “so exactly over his own that he hardly felt them, except the difference they made in his hearing” (Craik 71), allowing him the chance to hear “the sounds of the visible world, animate and inanimate” (Craik 71). Prince Dolor is not deaf or hard of hearing, but he was ostracized from his community and forced into a life of near isolation in a tower, due to the disability in his legs resulting from being dropped during his Christening. The silver ears for him act almost like a stethoscope, in which he can hear the surrounding world even better, and at least somewhat feel more included or involved in society; he can feel freer. Although real hearing aids or assistive devices are not nearly as fantastical as within Craik’s fairy tale, the use of something like the Trumpet Headband would, like Prince Dolor’s silver ears, provide more access and connection. To those who were deaf or hard of hearing in the Victorian era, having a Trumpet Headband could create more opportunity to work and converse. Hearing aids, both from the past and modern, similarly to glasses, fit in with the medical model of disability, in which people or their “abnormalities” are seen as needing “fixing,” rather than the surrounding environment or attitudes. The intent to conceal also gives off the impression of shame and stigma surrounding the disability. Despite this, they also encourage independence, freedom, and acceptance.

Despite the use of prosthetics to “fix” or “cure,” they are not a bad thing; for some, they are completely life changing (ex. more independence), as they broaden opportunity. Prosthetics can arguably have positive or negative connotations attached, depending on the surrounding (societal) expectations, the agency of the individual choosing prosthesis, and how necessary the prosthetic is in relation to accessibility, etc.

Fig. 7. Craik, Dinah Maria Mulock. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Warwick Goble, Project Gutenberg, 2007. www.mirrorservice.org/sites/ftp.ibiblio.org/pub/docs/books/gutenberg/2/4/0/5/24053/24053-h/images/illus-027l.jpg.

In this image, we see Prince Dolor use his cloak to room around the kingdom – it is his only sense of freedom when trapped in the tower. Prosthetics are not just physical aids; they also play a role in shaping self-identity and emotional well-being. Dolor is confined to a tower, isolated because of his perceived weakness. His journey with the magical cloak helps him develop confidence, self-reliance, and wisdom. Similarly, real-life individuals who use prosthetics often go through a psychological journey of self-acceptance and adaptation, realizing that their abilities and worth are not solely defined by physical limitations.

Fig. 8. Craik, Dinah Maria Mulock. The Little Lame Prince and His Traveling Cloak: A Parable for Old and Young. Illustrated by Dorothy Bayley, 1900. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_little_lame_prince_and_his_traveling_cloak_-_a_parable_for_old_and_young_%281900%29_%2814577025870%29.jpg.

Prosthetics are typically designed to restore physical function, allowing individuals to gain or regain independence. The magical traveling cloak functions similarly to a prosthetic device, as it compensates for Prince Dolor’s inability to walk, granting him the freedom to move beyond his physical constraints. The cloak, much like modern prosthetics, does not "cure" his disability, but provides a means for him to fully experience the world, much as a wheelchair or artificial limb does for real-life individuals with mobility impairments. In this image, we see Prince Dolor ruling over his people and having control and command. While Prince Dolor never regains the ability to walk, he ultimately proves that he is capable of ruling wisely and compassionately, demonstrating that leadership and intelligence are not tied to physical ability, despite common thought at the time (ie. being labelled as deaf and dumb). This reflects a broader perspective on prosthetics: they do not erase disability but rather provide individuals with alternative ways to engage with the world. The cloak, like a prosthetic, does not "fix" Prince Dolor but empowers him to navigate life on his own terms.

Fig. 9. Science Museum Group Collection. Pair of Wooden Crutches, 1901-1920.

https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co127160/pair-of-wooden-crutches-1901-1920

These crutches made of wood from the year 1901-1920 assisted individuals with mobility issues. These prosthetic devices are simple, yet they offer people with mobility issues a sense of independence, allowing them to feel freer. In The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak, Prince Dolor has a mobility issue and is unable to walk, which leaves him trapped in the tower. Prince Dolor has a magic cloak that enables him to travel, which creates a similar sense of freedom and independence that these wooden crutches might have done for people with mobility issues in Victorian times. Similarly to the cloak, these crutches can provide a sense of strength and confidence to these individuals. The reality of the matter is that there is no device like the cloak that can just completely magically wipe a mobility disability away, but we do have prosthetic devices that can aid in this issue. This also touches upon the stigma created around disability during Victorian times, where it was often viewed as a burden, hence locking Prince Dolor away. Prince Dolor’s magic cloak was a fantasy solution that made this “burden' disappear” (Craik 40). However, these prosthetic devices do not erase mobility issues, but they help give strength and independence to an individual in need.