Created by Alice Condry-Power on Mon, 11/14/2022 - 11:15

Description:

Although alcoholism wasn’t considered a disease until the 1860s, it wreaked havoc on Victorian society. The Victorians understood that feelings of drunkenness accompanied alcohol consumption, but they were unaware they could become addicted to this sensation. Similarly, during the Brontës' time, the general public did not understand that habitual drinking was a disease that required medical treatment. Emily, Charlotte, and Anne Brontë understood this phenomenon personally as their brother, Branwell Brontë, succumbed to the seductions of alcohol. The sisters saw the dark side of alcohol, and so they, Emily and Anne in particular, incorporated these observations into their writing. In Wuthering Heights (1847), Emily created the character of Hindley Earnshaw, who turns to alcohol in a time of psychological distress reminiscent of the situation that pushed Branwell to drink. In the same vein, in her Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848), Anne depicts Arthur Huntingdon, who abuses his wife due to his attachment to alcohol. His wife, Helen Graham, decides to leave him once he starts influencing their young son to drink. Huntingdon’s character is once again symbolic of Branwell, who was a frequent patron of the Black Bull, the local pub in Haworth. The bar stool of Branwell--who spent his last days writing friends begging money for gin--now finds its place in museums and as the subject of paintings.

“Antique Case Gin Bottle Glass, Olive Green Dutch Blown, ca. 1800,” Ebay, 2022. Pictured is a gin bottle that is symbolic of this popular drink in the 1800s. The Victorians mainly drank alcohol for its thirst-quenching properties since safe drinking water was rare; people drank water boiled for tea or distilled as ale. However, socialization, pain relief, perceptions of increased physical stamina, and drunkenness motivated alcohol consumption as well. Although the state of being drunk was understood at this time, drinking and alcoholism were not distinguished until about 1860. Experiments done in America in the 1860s-70s revealed that people who drank habitually required medical treatment. Gin, the alcohol that filled the bottle pictured here, was a particularly common choice of drink for Victorians as it was inexpensive, so it came to be known as a “poor man’s drink.”

Sources: Castelow, Ellen. “Mother’s Ruin.” Historic UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Mothers-Ruin/#:~:text=Gin%20was%20hawked%20by%20barbers,nine%20pence%20on%20strong%20beer. Accessed 6 December 2022; Harrison, Brian. Drunk and the Victorians: The Temperance Question in England 1815-1872. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1971.

John M. Burns, “Drunken Hindley Earnshaw,” Wuthering Heights: The Graphic Novel, Classical Comics, 2011. In this Wuthering Heights graphic novel, artist John M. Burns depicts Hindley Earnshaw violently drunk after the death of his wife. Certain keywords selected by the adaptor, Sean Michael Wilson, reveal the reasons why someone may turn to alcohol and the ways in which a person can be transformed by drink. The graphic novel reads, “His sorrow was of that kind that will NOT lament,” and so he “gave himself up to RECKLESS dissipation” (64). The words "not" in bold and caps and "reckless" indicate Wilson’s choice to depict Hindley’s desperation, which has led him to make decisions without thinking. Hindley’s actions represent those of other Victorians who were seduced by the bottle after traumatic moments in life. Similarly, Burns’s illustrations of Hindley depict the ways in which alcohol has made him looks crazed and his movements uncontrollable; his flailing limbs and pained expression show Hindley is figuratively “possessed” by alcohol. It is clear that Wilson and Burns made these artistic decisions based on Emily Brontë’s own depictions of Hindley’s drunkenness; Emily writes in the original text, “[Hindley] has spent the night in drinking himself to death … we heard him snorting like a horse” (144). Brontë successfully demonstrates the most serious side effect of excessive drinking: death. Hindley's death is first preceded by a description that resembles apoplexy, a common sign of alcohol poisoning. Similarly, Emily illustrates the transformative properties of alcohol by comparing him to a horse. Like Hindley in the graphic novel, Hindley in the novel is taken over by the powers of alcohol. Brontë is showing her audiences that alcohol is not merely a painkiller, or a socialization device, but a poison that can cause death while stripping away humanity.

Sources: Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. 1847. W.W. Norton & Company, 2019; Lock, Pam. “Brontës under the influence: the legacy of Branwell’s drinking.” TheConversation, 23 October 2017, https://theconversation.com/brontes-under-the-influence-the-legacy-of-branwells-drinking-85649#:~:text=Branwell's%20drinking%20became%20problematic%20in,or%20his%20love%20was%20unrequited.

Valentina Catto, “Young Arthur Under the Influence,”Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848), by Anne Brontë, Folio Society, 2020. In this Tenant illustration, Valentina Catto depicts Huntingdon’s corruption of Arthur against Helen’s will. Huntingdon encourages his young son to drink wine with him and his friends, so Helen worries that Arthur will grow up to be an alcoholic like his father. The darkness of Arthur’s denerate friends and his own clothing as well as the objects on the table are symbolic of alcohol’s destructiveness. Similarly, the contrast of the red wine against the dark backdrop demonstrates the power that alcohol has over these men while the dark red color reveals the seductive nature of wine. The three wine glasses also lie in the center of the image, which immediately draws the eye, paralleling Arthur’s addiction to alcohol. Underneath these glasses, young Arthur sits, staring into the eyes of the perceiver. The boy's blue-eyed stare, peering above the wine glasses, allows the audience to feel the guilt and resentment Helen feels towards Arthur’s corruption. The audience realizes that his blonde-haired, blue-eyed youthful purity will soon be diminished by the alcohol he’s holding and the black clothes he’s wearing. The depiction of Helen in the background is also important since she stands as a beacon of hope for Arthur’s salvation. Her bright yellow dress stands out from the black clothes of the men surrounding Arthur. Also, she is partially covered by the door, which conveys Helen’s determination to defy her husband and risk remaining in her son’s life. Catto also does a good job in exposing the melancholy and anxiety that Helen feels surrounding the relationship between young Arthur and Huntingdon; she is unable to look directly at Arthur and instead stares to the side. It is too painful for her to observe how her young son is being pressed with alcohol, but she must remain in the room in order to protect him from this temptation.

“Branwell’s final letter,” 1848, The Conversation, University of Leeds. In this 1848 letter, Branwell Brontë desperately asks his friend John to buy and bring him gin. It is also significant that he asks for the gin to be “speedily bought”--suggesting his urgency for his alcohol fix. Branwell also creates a plan for a hand off for the gin because he does not want his father to discover his continued drinking habit. Branwell's addictions to opium and alcohol masked his tuberculosis. This is the final letter that Branwell wrote. Branwell went to the grave begging for drink.

Sources: Lock, Pam. “Brontës under the influence: the legacy of Branwell’s drinking.” TheConversation, 23 October 2017, https://theconversation.com/brontes-under-the-influence-the-legacy-of-branwells-drinking-85649#:~:text=Branwell's%20drinking%20became%20problematic%20in,or%20his%20love%20was%20unrequited.

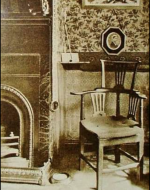

1800s period piece of “The Black Bull Chair,” The Black Bull Haworth, Facebook, 2022. The Black Bull is a pub located in Haworth that Branwell Brontë frequented, and this was his favorite chair. Branwell was a usual patron at the Black Bull, and his frequency there increased in 1845 after a crisis occurred between Branwell and his employer’s wife, Mrs. Robinson. Branwell sat in the parlor of the bar close to the bellto ring for service and a fire to keep him warm. After Branwell died, the landlord kept the chair for 18 years; he may have done this because he was quite fond of Branwell. The chair travelled to the Brown’s Brontë Museum, which became the Brontë Parsonage Museum. In the Black Bull to this day sits a replica of Branwell’s chair.

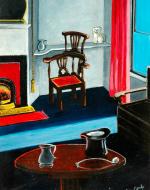

Eileen Ganly, “Branwell Brontë’s Corner at the ‘Black Bull,’” Brontë Parsonage Museum, 1977. This image is Eileen Ganly’s interpretation of Branwell’s favorite chair in the Black Bull. To the left of the chair, we can see the fireplace and the service bell, details of how the Black Bull looked in Branwell’s time. Ganly also inserts objects that Branwell owned and that he probably brought with him to the pub. These objects include his tankard, pipe, and top hat. By illustrating these objects in her painting, Ganly creates a realistic interpretation of Branwell; the perceiver feels as if they have stepped into the historical Black Bull during Branwell’s time to witness him drinking gin. Ganly’s promiment color choices are also noteworthy as they are demonstrative of alcoholism’s encroaching darkness on Branwell’s life. Ganly uses strong shades of red, blue, white, and gold, but then pairs them with dark shades of brown and black. She depicts light coming through the window with a thick blue line running across on a diagonal through the painting, but the blue color does not shine on the chair. Instead, the viewer imagines that Branwell only found warmth in the fire of the Black Bull, which itself stands as a symbol for alcohol. Did Branwell find solace drinking while sitting in the object leading him closer and closer to his death?