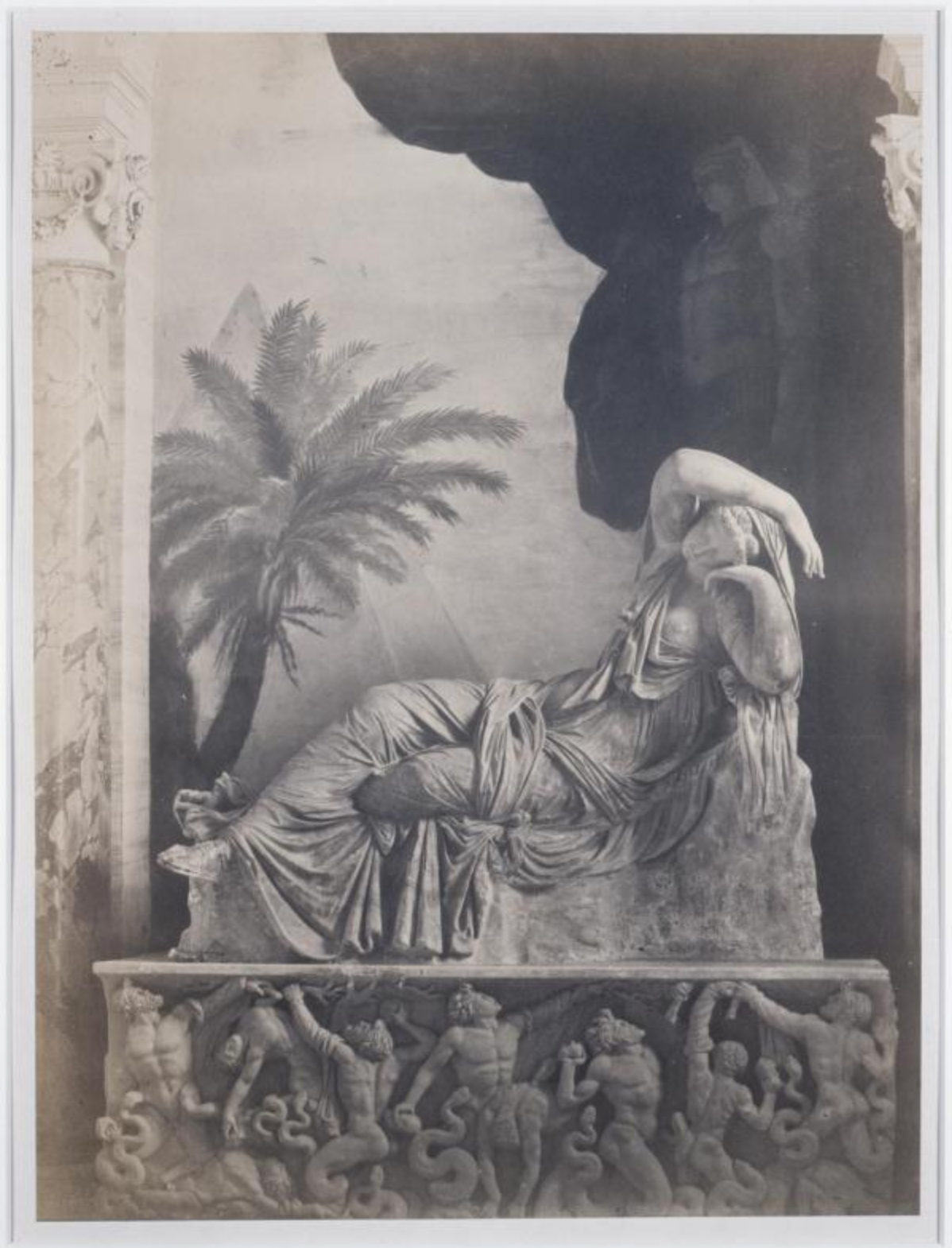

The sculpture of the Sleeping Ariadne is a marble copy of a 2nd century BCE Greek original from the school of Pergamon. Purchased by Pope Julius II in 1512 from the collection of Angelo Maffei, the sculpture was originally housed—atop a Roman sarcophagus and adapted to accommodate a fountain—in the Cortile delle Statue (Courtyard of Statues, Vatican) alongside the recently unearthed Laocoön and Apollo. Relocated several times, it was permanently installed in Galleria delle Statue (Statue Gallery) of the Vatican Museums in the late 1700s. George Eliot’s description of the sculpture in an exchange from her 1871 novel Middlemarch (set in the 1830’s)—"[t]he reclining Ariadne, then called Cleopatra, lies in the marble voluptuousness of her beauty, the drapery folding around her with a petal-like ease and tenderness” (Rischin 1124)—reflects the initial and long-held misidentification of the figure as Cleopatra, a misconception that persisted well into the 19th century. However, as early as the late 18th century, the pioneering Hellenist J. J. Winckelmann expressed his skepticism regarding the widely accepted and largely uncontested identification of the figure as Cleopatra—a consequence of the misinterpretation of the serpent-shaped bracelet as the asp by whose bite Cleopatra perished—but did not go so far as to unequivocally declare her Ariadne. Rather, he tentatively suggested she might be either a nymph, or perhaps even Venus. Shortly thereafter, Ennio Quirino Visconti—the highly regarded art historian and antiquarian who, in addition to serving as the papal Prefect of Antiquities, published the definitive scholarship on the Roman sculpture and antiquities of the Vatican collections in a six volume catalogue raisonné—recognized the sculpture as Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos of Crete who lay sleeping on the island of Naxos after being abandoned by Theseus, mythical king and founder of Athens, whom she helped escape the labyrinth. Despite the correction, the sculpture remained in a niche decorated with stereotypical Egyptian motifs (as seen in the photo) well into the late 1800s. By the mid-19th century, not only was the new attribution universally agreed upon by the cognoscenti, but casual museum-goers as well would have been aware of the Ariadne-Cleopatra controversy and its subsequent resolution. Even the most perfunctory of travel guide entries underscored its debated history. Murray’s—in which the sculpture is classified as "one of the most interesting" in the Vatican museum—identified the piece as “the celebrated recumbent statue of Ariadne, formerly called Cleopatra, because the brace-let bears some resemblance to a serpent" (Rischin 1131). Regardless of whether she has been erroneously believed to be Cleopatra or more accurately regarded as Ariadne, the pose of the languid recumbent female with her arm wrapped around her head continued to be both imitated and emulated for five-hundred years and in various artistic forms: Michelangelo’s 1526–1531 sculpture Night —marking the Tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici in the Sagrestia Nuova (New Sacristy) in the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence—recalls it; Giorgio de Chirico’s 1913 painting Ariadne directly quotes it. Both timeless and universal in its appeal, in the Sleeping Ariadne, as Eliot observes—through the words of 19th-century German engraver Adolf Naumann in Middlemarch—"there lies antique beauty, not corpse-like even in death, but arrested in the complete contentment of its sensuous perfection” (Rischin 1125).

"Sleeping Ariadne" (Victorian Photographs by Robert MacPherson)

Type: Gallery Image | Not Vetted