See assignment on Moodle.

Timeline

Table of Events

| Date | Event | Created by |

|---|---|---|

| circa. 900 to circa. 146 | Ladies of Carthage (9th Century BC)At the end of Chapter 20, Mr. Rochester is speaking to Jane about his bride-to-be, Blanche. Mr. Rochester brags that Blanche is “[a] strapper—a real strapper, Jane: big, brown, and buxom; with hair just such as the ladies of Carthage must have had” (Bontë ch. 20). This is significant because Mr. Rochester is reflecting on Blanche’s looks, comparing her to women of a distant land, Carthage. Located in present-day Tunisia, Carthage was inhabited by Phoenician (Punic) merchants who traded throughout the Mediterranean (Docter et al. 11). The legend of the city’s founding derives from that of the Lebanese Phoenician ruler, Elissa (Dido), who journeyed with her followers from Cyprus while under political duress (Docter et al. 11). The attached image is a depiction of a Phoenician woman, possibly resembling Dido. Carthage was a prosperous nation for centuries until its demise in 146 BC at the conclusion of the Third Punic War (Docter et al. 12). Connecting back to the text, it is significant that Mr. Rochester compares Blanche to a woman of Carthage because she is described as having a darker complexion. Women of a darker complexion often have natural hair that is deeply pigmented and/or curly. It is not known exactly what present-day race classification the Phoenician’s fall under. However, it is thought that they were a variety of people from “ancient Near East,” including those of Middle Eastern and northern African descent (Gill). Given this information, Brontë provides a breadcrumb for the reader to consider regarding the race of the upper crust society at the time. As discussed in class, the stereotype for 19th century wealth is that of the white aristocrat. Brontë is disrupting this stereotype with characters like Blanche who do not fit the “lily-white” bill, introducing the notion that the wealthy might have been different races entirely. Docter, Roald, et al. “Carthage. Fact and Myth: Fact and Myth.” Sidestone Press, 2015. pascal-ccu.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01PASCAL_CCU/177fn98/cdi_askewsholts_vlebooks_9789088903526, Accessed 13 Jun. 2022. Gill, N.S. “Was Hannibal, Enemy of Ancient Rome, Black?” ThoughtCo. 2019, www.thoughtco.com/was-hannibal-black-118902#:~:text=The%20Carthaginians%20were%20Phoenicians%2C%20which%20means%20that%20they,and%20Hebrews%29%2C%20which%20included%20parts%20of%20northern%20Africa., Accessed 13 Jun. 2022. |

Emily Johnson |

| circa. 1000 to circa. 1850 | Coverture in 19th Century EnglandA reading or viewing of Jane Eyre is grossly incomplete without a legitimate attempt at understanding the aspects of coverture. Coverture's existence in 19th century England was nothing short of financially, socially, and religiously damning for women's gendered status. This legal doctrine, as explained by author Margot Finn in their article, "Women, Consumption and Coverture in England c. 1760-1860" explains how coverture "subsumed a married woman's legal and financial identity under that of her husband" (Finn) and essentially removed women from the legal perspective. The doctrine worked hand-in- hand with the social attitudes at the time to produce a hyper misogynistic society, ultimately resulting in a lower class status for women. The results of the doctrine are felt in totality throughout the tale of Jane Eyre as Jane is consistently placed in social situations in which she has been stripped in entirety of her power, dignity and often her humanity. While through the first portion of the text she has been single/ unwed, Jane has had to seek her own terms of employment due to the lack of financial resources she has acquired as a woman during this time. Coverture is not necessarily a singular legislative piece that had an instantaneous impact on the novel, but rather an overwhelming shadow presented over the entire story which seeps into every interaction Jane experiences. Coverture’s reach is both wide and ominous while poisoning the ability for Jane to pursue any sort of social mobility. |

donovan moore |

| 1604 | The Bigamy Act of 1604In Chapter 26 it was revealed, at what was supposed to be Mr. Rochester and Jane’s wedding, that Mr. Rochester was in fact already married and his wife was still alive. Although Briggs objected to the marriage prior to the “I Do’s,” Mr. Rochester was still guilty of attempted bigamy. Prior to 1604 bigamy was not an actual crime, but a moral and religious offence for which the church would determine the repercussions. In 1604 the act of taking more than one wife was decided to be more than just a social issue and was officially declared a felony. Divorce and remarriage were also illegal at the time, so despite the law against Bigamy it was fairly commonplace for “people whose marriage had failed or whose spouse had deserted [to venture] to marry again” (Capp). From today’s lens it is easier to see that the position in which one is unhappy in a marriage but is legally forced to stay with their spouse or be single is an incredibly difficult one to be in, one almost worthy of empathy. In the 1800’s, however, the church had such a crucial role in the legal and social realms that the mere thought of divorce was blasphemous. This begs the moral question, should Mr. Rochester be able to seek happiness if his wife is not the companion he desired? Or is he destined to live a life that does not offer him the fulfillment he claims to be able to find in Jane? This is made even more complex by the earlier allusion to Bluebeard in relation to the circumstances in which they find Mrs. Rochester. Is Mr. Rochester Bluebeard? Did he drive his wife to madness and hide her on the third floor so others would not know of his actions? He has shown throughout the novel that he is manipulative and emotionally abusive, and it is known that Jane does not have a keen eye for stable relationships. He continually uses money and status to essential bribe Jane into loving him and staying in Thornfield. The fact that he hid the existence of his wife, of the marriage, from the woman he was claiming to love does not bode well for his character analysis. Mr. Rochester is excited by being desired, by the idea of having whatever is seemingly off limits—Jane. Once he marries Jane and the chase is over, will those feelings he says he has for her fizzle out? She could most certainly end up like another one of Bluebeards wives, locked away in Mr. Rochester’s attic only to be kept a secret from his next conquest and declared mad upon discovery. Or, considering how young Jane is, could she be Bluebeards youngest wife? The one that escapes and either kills Bluebeard or is rescued from him by a young man—another potential suitor perhaps. The significance of Mrs. Rochester burning Mr. Rochester in his bed carries even more weight now. He was committing acts of the devil, both in keeping her locked up and in his continual romantic conquests. Despite her madness, it could be thought that she was trying to communicate with Jane, to keep her from suffering the same fate. The discovery of Mr. Rochester’s bigamous acts has added a layer of complexity while also bridging the gap between so many earlier allusions and interactions, it is a pivotal moment in the novel.

Capp, Bernard. “Bigamous Marriage in Early Modern England.” The Historical Journal, vol. 52, no. 3, 2009, pp. 537–56. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40264189. Accessed 16 Jun. 2022. |

Hailey Ensor |

| 28 Oct 1726 | Gulliver's Travels, or Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, is PublishedIn chapter twenty-one of Brontë's novel, Jane Eyre decides to respond to the wishes of her dying Aunt Reed and return to her childhood home of Gateshead Hall. White glancing over the bookcases of the breakfast room, Jane recognizes that her most treasured novel, Gulliver's Travels, has remained where she last placed it (Brontë ch. 21). Gulliver's Travels was originally published on the twenty-eighth of October in 1726 with the title Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, and it was presented to have been a factual narrative written "by Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships (qtd. in "First Edition of Gulliver's Travels"). Jonathan Swift wrote the novel's four parts over a span of five years, drafting the first part in 1721-22, the second in 1722-23, the fourth in 1723, and the third part after them all in 1724-25 (Ehrenpreis 1957). The novel is considered to be a political satire of eighteenth-century English culture, and as such, it was met with much praise as well as much critique. Jane Eyre's repeated mention of the novel becomes incredibly significant when marking Jane's personal growth and her relation to the society that Brontë has mirrored. Brontë's inclusion of Swift's novel places Jane Eyre well within the bounds of England's literary society; only an educated woman would devote her time to the satirical masterpiece that is Gulliver's Travels. When Eyre recognizes her favorite novels on the bookcase, she notes that "the inanimate objects were not changed; but the living things had altered past recognition" (Brontë ch. 21). The physical existence of the novel reminds her of the life that she has lived and the changed woman that she has become. Though the novels have not changed, the woman that once read them has transformed.

Works Cited Ehrenpreis, Irvin. "The Origins of Gulliver's Travels." PMLA, vol. 72, no.5, 1957, pp. 880-99. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10/2307/460368. Accessed 13 June 2022. "First Edition of Gulliver's Travels, 1726." The British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/first-edition-of-gullivers-travels-1…. Accessed 13 June 2022. "Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World...By Lumuel Gulliver." ABE Books, https://pictures.abebooks.com/inventory/md/md30384571591.jpg. Accessed 13 June 2022. |

Savannah Funderburk |

| circa. 1750 to circa. 1811 | Village Schools Privately OpenedIn chapter thirty of Jane Eyre, Mr. St. John Rivers offers Jane the opportunity to live on her own and obtain a fraction of independence by working as a teacher. He grants her employment at his new village school where her "scholars will be only poor girls---cottagers' children---at the best, farmers' daughters" (Brontë ch. 30). Prior to the educational reform of the Victorian Era, the only way for young, poor girls to receive an education was to attend either a charity school or a village school. Most village schools were funded and built by private benefactors and entrepreneurs, and the students were mainly taught how to read and write (Harwood 5). Brontë's mention of the village school is significant to the establishment of Jane's position as an education woman in society. As a former governess to a wealthy charge, it would be considered beneath Jane to educate children of the lower-working class; the students would be deemed unworthy of her intelligence. When offering Jane the position, St. John Rivers appears hesitant and insistent on clarification, and it is because he does not want to offend or insult her by offering her a position in association with the lower class (Brontë ch. 30). Jane's acceptance of the position demonstrates her humility and suggests that she values her contribution to society more than she values her position in society.

Works Cited "A Class of Girls." iStock, media.istockphoto.com/illustrations/victorian-education-class-of-school-girls-19th-century-illustration-id1050385928. Accessed 20 June 2022. Harwood, Elain. "The Earliest Surviving Schools." England's Schools: History, Architecture and Adaptation, English Heritage, Swindon, 2012, pp. 5-17. Accessed 20 June 2022. |

Savannah Funderburk |

| Summer 1771 | The Death of Wolfe is Exhibited at the Royal AcademyAlong her journey to Thornfield Hall, Jane Eyre is first accommodated in Millcote at the George Inn. While describing the appearance of the Inn, Eyre recalls a mantlepiece adorned with prints of George the Third, the Prince of Wales, and "a representation of the death of Wolfe" (Brontë ch. 11). The representation of Wolfe she references is Benjamin West's masterpiece, The Death of General Wolfe. The painting was created to commemorate the loss of British General James Wolfe at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, or the Battle of Quebec, on the thirteenth of September in 1759 (de Bruin 2006). General Wolfe was heavily respected and loved, and the public mourned him as a martyr of the Seven Years War. Benjamin West created the painting in 1770 and presented the work at the Exhibition of the Royal Academy in 1771 ("The Death of Wolfe"). The Royal Academy of Art in England was one of the most significant art societies in Europe as it was supported by King George III, and West's inclusion the third Royal Academy Exhibition secured his future as an artist. Around 1773, The Death of General Wolfe found its place on the walls of Buckingham Palace, and in 1792, Benjamin West became President of the Royal Academy ("The Death of Wolfe"). Charlotte Brontë's reference to West's work places the reader within the political atmosphere of Jane Eyre. Though Eyre was unaware of the creator of the work, she was knowledgeable of the subject, which suggests familiarity between Jane and the event being referenced. Works Cited de Bruin, Tabitha. "Battle of the Plains of Abraham." The Canadian Encyclopedia, 7 Feb. 2006, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-the-plains-of-abrah…. "The Death of Wolfe." Royal Collection Trust, www.rct.uk.collection/407297/the-death-of-wolfe. |

Savannah Funderburk |

| circa. 1798 to circa. 1815 | Early 19th Century RomeMr. Rochester divulges the truth to Jane following the debauchery of their wedding day. After telling her about his early years with Bertha, Mr. Rochester then explains his travel. “For ten long years I roved about, living first in one capital, then another: sometimes in St. Petersburg; oftener in Paris; occasionally in Rome, Naples, and Florence” (Brontë ch. 27). This is significant because Mr. Rochester’s marriage to Bertha affords him “plenty of money,” as well as the ability to choose his “own society” because his marriage is not publicly known (Brontë ch. 27). Of the capitals Mr. Rochester lists, at the turn of the 19th century, Rome “was ruled by the pope, an elected monarch,” but would soon “fall to the armies of revolutionary France” lead by Napoleon (Nicassio 13, 15). This is important because at the time 21- to 30-year-olds made up “the largest single age group,” in Rome, though men outnumbered women (Nicassio 55). Mr. Rochester speaks of his female conquests, including his Italian mistress, Giacinta (Brontë ch. 27). At the time “Roman women had a reputation of beauty and independence” which were no doubt noticed by “the large floating population of unattached male pilgrims and tourists” who aided in outnumbering the female population (Nicassio 56). With the inclusion of Mr. Rochester’s travels to capitals like Rome, Brontë is further illustrating the divide between men and women, conflating the societal double standards of the genders in Jane Eyre. Nicassio, Susan Vandiver. “Imperial City: Rome Under Napoleon.” University of Chicago Press, 2005. pascal-ccu.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01PASCAL_CCU/nil3jg/cdi_proquest_ebookcentral_EBC485978, Accessed 18 Jun. 2022. |

Emily Johnson |

| 1800 to 1800 | Acts of Union 1800In chapter 23 of Jane Eyre, Mr. Rochester divulges to Jane that she is to be sent off to Bitternut Lodge in Ireland to become a governess to a new family. Jane immediately expresses discontentment towards the idea of being forced to relocate, especially due to the distance between her current residence at Thornfield and her new home-to-be in Ireland. The relationship between England and Ireland is rocky at best, no doubt due to the centuries old conflict dating back to the 12th century. It wasn’t until the Acts of Union in 1800 in which the parliaments of both Great Britain and Ireland joined to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Published in a book on the relationships of the U.K. titled Four Nations Approaches to Modern ‘British’ History, author and scholar James Stafford writes “Straddling the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and positioned between the fields of British and Irish history, the Union of Britain and Ireland can be seen, according to J.G.A. Pocock, as ‘the hinge … marking the transition from early modern to modern “British history”.’ 1 This usefully highlights both its importance, and its elusiveness” (Stafford). In this excerpt, Stafford alludes to the extreme importance the acts had on the two converging nations as the government's attempt to smooth over the rocky history. As the acts were constructed around a similar time as the novel, Brontë demands the reader utilize contemporary knowledge as they ponder the (albeit brief) moments in which Jane imagines a life outside Thornfield, thrusted into a life of political unrest. This unrest suits Jane’s reaction to the move, working in accordance to her emotional state of not wanting to leave her future lover. Stafford, J. (2018). “The Scottish Enlightenment and the British-Irish Union of 1801” In: Lloyd-Jones, N., Scull, M. (eds) Four Nations Approaches to Modern 'British' History. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-60142-1_5 The Union- No Grumbling. Published 1800, by W. McCleary |

donovan moore |

| 25 Mar 1807 | Slave Trade ActWhen Mr. Rochester arrives in Thornfield the estimated date is January of 1808, nearly one year after the Slave Trade Act “made it illegal to engage in the slave trade throughout the British colonies†(Abolition). The Rochester's, like most other wealthy white families at the time, came into wealth on the backs of slaves. On March 25th, 1807 the Slave Trade Act went into effect, but trading continued illegally until 1811. With slavery still heavily prevalent, Brontë alludes to it throughout the text. Jane was surprised by the warm welcome she received from Mrs. Fairfax, she had expected “only coldness and stiffness: this [was] not like what [she had] heard of the treatment of governesses†(Brontë ch.11). Jane associated the treatment of all ‘help’ with that of slaves—they were thought of as lowly and spoken down to. Earlier Jane calls her cousin, Jack, a “slave-driver†and describes how her cousins are abusive, exclusive, and lack compassion (Brontë ch. 1). Both instances make it apparent that slavery was a prominent aspect of life at the time and therefore a common association to make. Sue Thomas analyzed the relationship between Christianity and the Slave Trade Act in regard to Jane’s character development and proposed the idea that “Jane’s growth of religious feeling […] is […] grounded in her consciousness of the tensions between slavery and Christianity†(Thomas 57). With the introduction of Mr. Rochester and the development of his and Jane’s relationship, Jane picks up on characteristics that would be expected of a slave master—in fact, Leah addresses Mr. Rochester as “Master†upon his arrival (Brontë ch.12). While they are getting to know each other in chapters 13-15, Jane is exposed to his true personality and the terms associated with slavery are used less frequently. Perhaps this was a conscious decision Brontë made to present the societal expectations of Mr. Rochester and contrast them with his true character, or Jane’s perception of his true character that is. There are several references to the supernatural and religion throughout these chapters as well—increasing as their interactions continue—this ties into Thomas’ theory of the tug of war Jane was experiencing between religion and slavery. It is to be expected that this allusion to slavery will continue to be a major underlying component of the story considering its historical relevance at the time.

“Abolition of the Slave Trade†The National Archives, 1 Aug. 1836, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/abolition.htm#:~:text= Abolition%20of%20the%20Slave%20Trade%20Act%2C%201807&text=On%2 025%20March%201807%2C%20the,continued%2C%20regardless%2C%20until % 201811. Accessed 8 Jun. 2022. Thomas, Sue. “Christianity and the State of Slavery in ‘Jane Eyre.’†Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 35, no. 1, 2007, pp. 57–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40347124. Accessed 8 Jun. 2022.

|

Hailey Ensor |

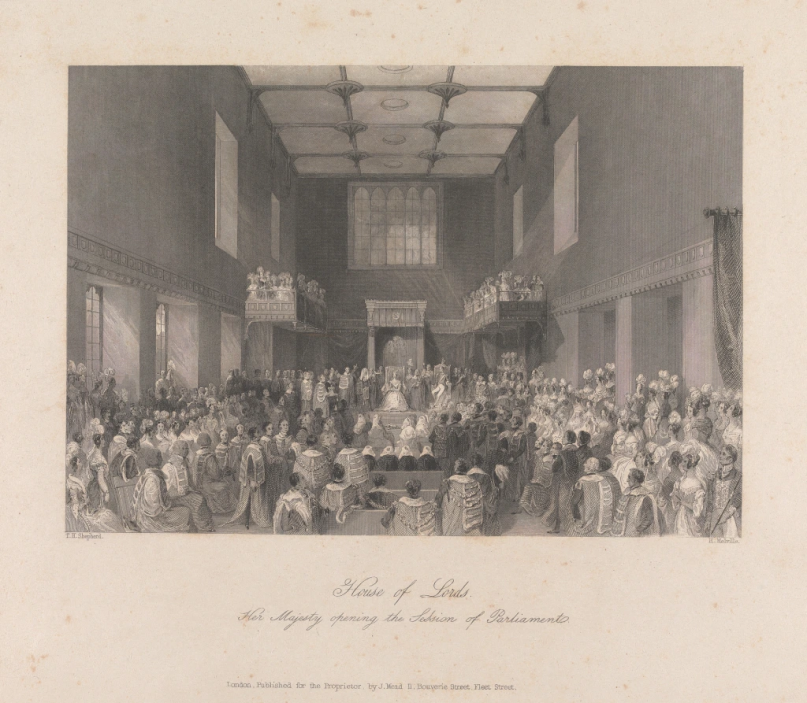

| The start of the month Jul 1837 | Wills Act 1837In chapter 33 of Jane Eyre, Jane is conversing with St. John about the troubling information he has acquired regarding an unknown orphan who has come into a large inheritance due to the orphan’s uncle passing away. It is revealed this orphan is none other than Jane herself, leaving her in a state of disbelief and shock after learning her financial citation has been completely flipped. Author Charlotte Brontë may have utilized the contemporary information at the time as the United Kingdom Parliament had recently passed the Wills Act 1837 prior to Brontë finishing the novel. The act states “A general devise of the real estate of the testator… shall be construed to include any real estate, or any real estate to which such description shall extend (as the case may be), which he may have power to appoint in any manner he may think proper, and shall operate as an execution of such power, unless a contrary intention shall appear by the will” (Parliament of the U.K.). The act provided all adults living in the U.K. the power of complete ownership over their wills and attempted to clear up any problems that had risen due to the death of a loved one. Due to the act, Jane’s uncle would have had an easier time designating exactly who his estate would be given to, specifically in terms of providing the estate to Jane and not her cousins who due to the common law at the time before the act may have been able to claim ownership to the estate. The existence of this act completely alters the trajectory of the plot and may have severely influenced Jane’s relationship with her family members.

Melville, Henry. “House of Lords: Her Majesty Opening the Session of Parliament.” The Victorian Commons. https://victoriancommons.wordpress.com/. Accessed 21 June 2022.

United Kingdom Parliament. Wills Act 1837. 3rd July, 1837. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1837/26/pdfs/ukpga_18370026_en.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2022 |

donovan moore |

| circa. 90 to circa. 110 | Pool of BethesdaThe Pool of Bethesda is referenced by Mr. Brocklehurst in Chapter VII of Jane Eyre. During a surprise visit to Lowood one afternoon, Mr. Brocklehurst describes to the teachers and pupils why Mrs. Reed has sent Jane to the school. “[S]he has sent her here to be healed, even as the Jews of old sent their diseased to the troubled pool of Bethesda; and, teachers, superintendent, I beg of you not to allow the waters to stagnate round her” (Bronte 67). The Pool of Bethesda holds a biblical connotation, as it is referenced in the Book of John (Masterman 88). John 5:2, 3 states, “Now there is at Jerusalem by the sheep gate a pool, which is called in Hebrew Bethesda, having five porches. In these lay a multitude of them that were sick, blind, halt, withered” (Masterman 88). It was believed that the Pool of Bethesda was a dwelling located at St. Anne’s Church in Jerusalem to which the poor and sick would flock seeking reprieve from their misfortunes in the twenty years between 90-110 AD (Masterman 88, 89). In terms of Brocklehurst referencing the Pool as “troubled,” it is in reference to “the sudden ‘troubling’ of water,” being the natural rise and flow of springs (Masterman 92). Mr. Brocklehurst’s reference to the pool deepens our understanding of the text in multiple ways. First, Lowood is a religious school for Orphan girls, so having a religious supervisor makes sense (Bronte). Second, the girls read scripture, like that in the book of John, and are expected to be raised with humility, so they can be likened to the “’sufferings of the primitive Christians’” like those who flocked to the pool (Bronte). Third, Mr. Brocklehurst is eluding that Jane is "sick," pleading with the teachers to not let her tarnish the other pupils, via his use of a religious metaphor (Bronte). Masterman, E. W. G. “The Pool of Bethesda.” The Biblical World, vol. 25, no. 2, 1905, pp. 88–102. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3141150. Accessed 6 Jun. 2022. |

Emily Johnson |