The popularity of the Victorian valentine arose in the 1840s, following the reform of the Penny Post. James Beaton wrote a poem predicting the rise of posted valentines: “The letters in St. Valentine so vastly will amount, / Postmen may judge them by the lot, they won’t have time to count; / They must bring round spades and measures, to poor love-sick souls / Deliver them by bushels, the same as they do coals.” Victorian valentines were often handcrafted by men and women. There were different types of valentines, such as the flaming valentines which were strong declarations of love, vinegar valentines which were offensive and usually sent to enemies, comic valentines which poked fun at bachelors and the concept of courtship, love valentines, and missives for family and friends. The valentine in Elizabeth Gaskell's Mary Barton (1848) plays a vital role of driving the romantic and political threads of the plot along as it travels through different hands: Jem's, Mary's, Mr. Barton's, Esther's, and finally back to Mary's.

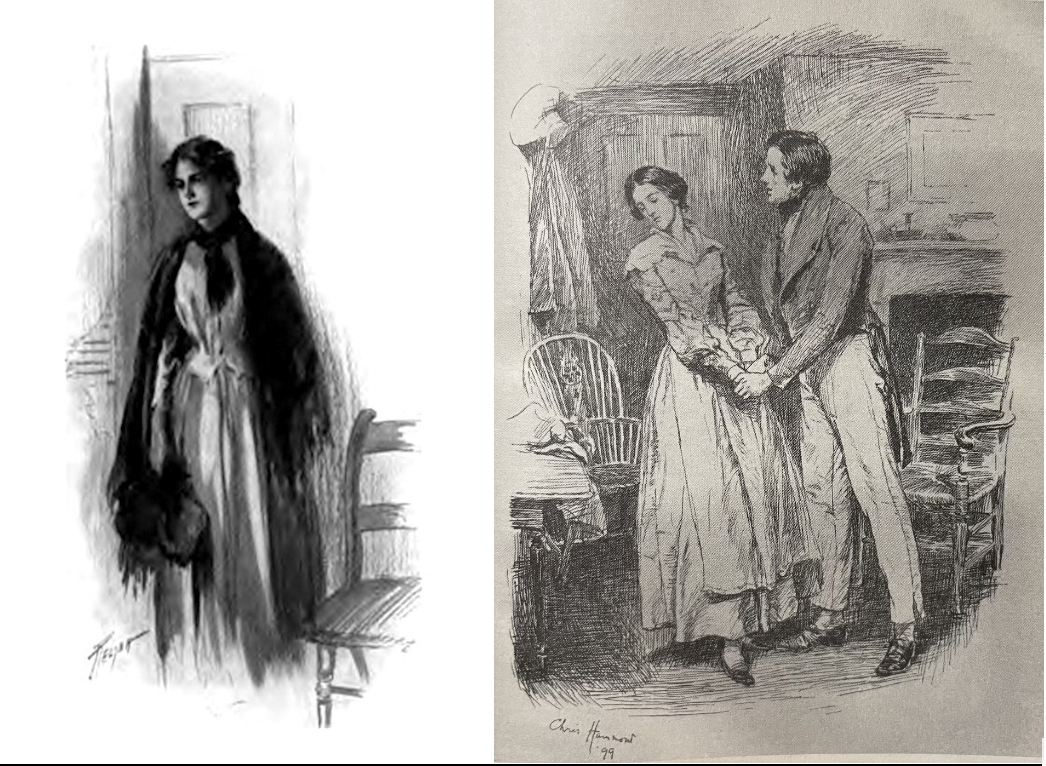

Left: Charles M. Relyea, "Frontispiece," for Elizabeth Gaskell's Mary Barton, 1907, The Victorian Web. Right: Chris Hammond, "'You won't even say you'll try and like me; will you, Mary?,'" in Gaskell's Cranford and Mary Barton, 1899.

Relyea’s illustration (on the left) for Elizabeth Gaskell's 1848 novel depicts Mary Barton, the protagonist of the novel, who receives a sincere valentine from Jem Wilson. The valentine is “all bordered with hearts and darts” (101), a decoration which symbolizes Jem’s deep love for Mary. He sends it anonymously as her secret admirer, but Mary “[suspects it] to come from Jem” (101). Jem loves Mary and proposes to her: "'I’ve a home to offer you, and a heart as true as ever man had to love you and cherish you; we shall never be rich folk. I dare say; but if a loving heart and a strong right arm can shield you from sorrow, or from want, mine shall do it'" (115). Jem pours his heart out to Mary, but she declines because she does not realize her warm feelings for Jem when she initially receives the valentine because of her infatuation with the charming, yet deceptive Harry Carson. Hammond's illustration (on the right) displays the heartbreaking moment when Jem pleads, "'You won't even say you'll try and like me; will you, Mary!'" (116). She falls for Harry's charms at first; however, she comes to understand Harry's true intentions: “'You may think I am a fool; but I did think you meant to marry me all along; and yet, thinking so, I felt I could not love you […] I don’t think I should loved you now you have told me you meant to ruin me'” (123). Harry never sends Mary a love valentine, which foreshadows his dishonesty in desiring to engage in a relationship without a promise of marriage. Love is a game of conquest in Harry's mind—he does not mind if he ruins Mary’s reputation, and he chases other women. Conversely, in sending Mary a valentine, Jem reveals his affections for Mary and only wants to be with her.

Unknown, Valentine, 1850s, The Victorian Web.

This pop-up valentine was created in Germany around the 1850s, and it is an intricately designed valentine with a basket overflowing with flowers, birds adorning the rim, and two angels with hammers. Victorian valentines usually included motifs such as hearts, cupids, churches, and flowers. Flowers possessed different meanings: red roses symbolized love, pansies symbolized thoughts, and lilies of the valley represented the "return of happiness." The flowers in this valentine convey the love of the sender for the recipient. In Mary Barton, we read clues about Jem's valentine to Mary: "hearts and darts" and "the piece of stiff writing-paper" (101, 205). In addition, Mary uses Jem's valentine to write Samuel Bamford's poem: "on a blank half sheet of a valentine" (101). The valentine appears to have enough room for Mary to copy a long poem because Bamford's verse is five stanzas; thus, the size of Jem's valentine must be ample. The valentine begins in Jem's hands as he either purchased or assembled it for Mary, but it travels to Mary's hands. In her hands, the valentine represents Jem's love and affections. The motif of the "hearts and darts" reveals his loving intentions to capture Mary's heart with the metaphorical cupid's darts. The larger size of Jem's valentine may also symbolize the grand nature of his love.

William Lovett, The People's Charter, 1838, The British Library.

This image displays the first pages of the The People's Charter, which was written by William Lovett, who outlined the ideologies of the Chartist movement. Lovett called for universal suffrage, meaning the right to vote for men over 21 who were not felons and did not have mental disorders. He also wrote in favor of removing the property qualification to allow for people of different classes to run for elections, instigating annual parliaments to keep the government in check, ensuring equal representation through dividing the United Kingdom into 300 districts with one representative for each, granting payment for the members, and allowing for voting by secret ballots to ensure fairness and protection of voters. In Chapter IX of Mary Barton, Job Legh recites Samuel Bamford's poem about the sufferings of the poor and the poor's pleadings to God for release from their pain because the upper class members fail to act or address their needs and concerns. Bamford was a working-class poet, but he was not a Chartist. However, Bamford's poem resonates with John Barton, and he asks Mary: "'Mary! wrench, couldst thou copy me them lines, dost think?'" (101). Mary copies Bamford's poem on "a blank half sheet of a valentine" (101), Jem's valentine; thus, the valentine carries a political message, but it retains the love aspect, which expands from romantic love to love of neighbors. The poem mentions the hardships of "A female crouching there, so deathly pale," the "yon famished lad, / No shoes, nor hose, his wounded feed protect," and "A bowed and venerable man is he; / His slouched hat with faded crape is bound." (100). The valentine's references to many people arguably foreshadows how the poem will travel through other characters' hands. After Mary copies the poem, the valentine will move into the hands of John Barton, a member of the Chartist movement who despises the way that the upper reaches treat the impoverished working class.

"The Cotton Famine - Group of Mill Operatives at Manchester," The Illustrated London News, 1862, The British Library.

The illustration depicts unsatisfied workers who have gathered outside of the cotton mill. The men and women have their hands on their hips to signal their anger and disappointment towards the mill owners. In Mary Barton, this type of protest gathering parallels the Chartist meeting when the working men voice their concerns to their supervisors, but the indifferent bachelor Harry Carson, son of mill owner John Carson, mocks their sufferings. Harry sketches a caricature of the working men: “lank, ragged, dispirited, and famine-stricken” (163). However, his caricature is picked up by one of the workers, and they seek revenge. Since the workers feel ignored, the workers take matters into their own hands and take lots on who will kill Harry. Mr. Barton is the one who pulls the trigger and murders Harry.

Jonathan King, Valentine, 1860-1880, Museum of London Collection.

King was a famous valentine maker; he made and sold beautifully crafted valentines. This valentine is comprised of white lace attached with paper strings or hinges, which makes the valentine appear three-dimensional, and there are paper flowers all on stiff cream paper, recalling the stiff material used in Jem's valentine. After Mr. Barton uses a piece of Jem's valentine for wadding in his gun, the discarded paper sits on the grass. The valentine is no longer in Mr. Barton's hands but on the ground; however, Esther stumbles across it and picks it up: "She stepped forward to examine. It proved to be a little piece of stiff writing-paper compressed into a round shape" (205). Esther acutely draws the connection that the paper was used as "wadding for the murderer's gun," and she recognizes the handwriting: "it was Jem's handwriting!" (206). She also sees Mary's name on the valentine (206). Now, the valentine is in Esther's hands, and the pieces are fitting together. Additionally, since the valentine is ripped, "a letter or two was torn off," it is breaking down and breaking apart because the valentine is not meant to be used as an instrument of evi. The valentine drives the plot along as Esther hurries to Mary to provide her with the evidence that Esther fears convicts Jem but Mary realizes convicts her father.

Edouard Rischgitz, "Divorce Court," 1870, Hulton Archive.

Rischgitz's artwork displays a divorce court with a woman at the stand testifying. In Mary Barton, the court scene might have looked similar when Mary testifies to Jem's innocence, she burns the evidence of her father's wrongdoing: "she carried the paper down-stairs, and burned it on the hearth, powdering the very ashes with her fingers, and dispersing the fragments of fluttering black films among the cinders of the grate" (216). The valentine, returned to the original recipient, carries characteristics of romantic love, political fervor, death, violence, and power to reveal Mr. Barton's culpability. By burning the valentine, Mary is cementing her love for her father and Jem because she wants to protect both from being condemned. She thus makes the journey to Liverpool by train to stand bravely in court, much as this female character Rischgitz depicts in an authentically rendered courtroom.

Ivor Symes, "'O Jem! Take me home.,'" for Gaskell's Mary Barton, 1905 edition.

Symes's illustration displays Mary holding onto Jem's arm while they are walking together after she recovers from her illness following the trial where the courts deem Jem innocent. She states to Jem, "'O Jem! Take me home.'" The romantic valentine has completed its mission because Jem and Mary are finally reunited and in love. Jem brings Mary back to Manchester to be with her father, who is dying. During the final moments of his life, John Barton realizes the depth of his crime in murdering Harry, and his final words are, "'God be merciful to us sinners. Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them that trespass against us'" (Norton 321). The valentine plays a bittersweet, yet vital role in bringing destruction in being the wadding for the bullet that kills Harry, but it also brings enlightenment in the aftermath of Barton's understanding of his transgression and Harry's father, mill owner John Carson, taking initiative to reform the poor treatment of workers, the motivation for his murder. Lastly, the valentine brings Mary and Jem together, and the memory of John Barton lives on in Mary and Jem's baby son named Johnnie (339). The political and romantic aspects of the valentine's legacy live on.