Who Shot Ya?

Created by Paige McCusker on Fri, 03/29/2024 - 12:04

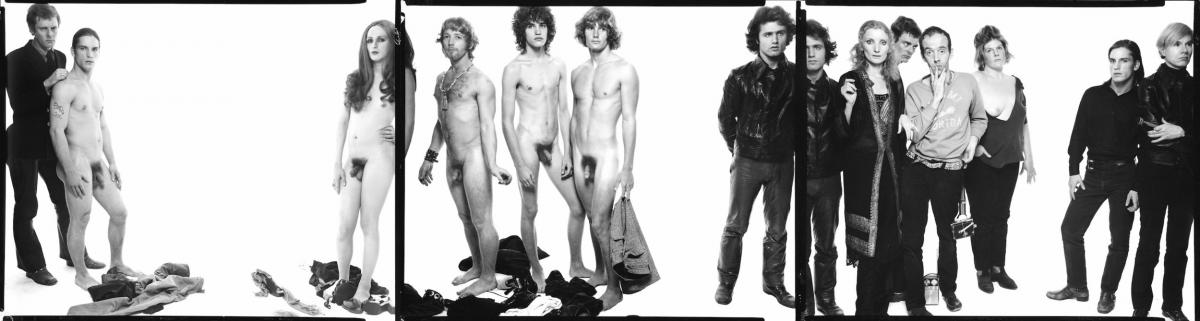

This timeline will provide sociohistorical context to Richard Avedon's 1968 photograph, Photo of Andy Warhol and members of The Factory.

Avedon, Richard. Photo of Andy Warhol and members of The Factory. 1969. https://www.avedonfoundation.org/the-work. Accessed 29 March 2024.

Timeline

Chronological table

| Date | Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 Mar 1963 |

Avedon's political workRichard Avedon started out as an advertising photographer in 1944 before moving to fashion photography in 1945 (nytimes.com 2004). He would stay in fashion photography and move to taking photographs of those like the Chicago Seven, a counterculture group targeted by the DOJ for attempting to protest the DNC in 1968, and members of The Factory (nytimes.com 2012). His other photographic subjects include a victim of napalm, the SNCC led by Julian Bond (pictured above), the destruction of the Berlin Wall, and those who were institutionalized (avedonfoundation.org). Avedon's work, especially photographing members of The Factory and Warhol, is a snapshot of American life at the time of the 1960s, marked by turbulence and counterculture. Warhol’s own works are no different, showcasing his avante-garde inclinations (how many conformists would consider photographing those who are considered outsiders?). Both Warhol's and Avedon's works would shape 1960s pop (counter-) culture and, in turn, reflect counterculture; and neither of them flinch from what might be considered provocative (Avedon's subjects have been spoken for; Warhol's film works would barely follow the Hays Code, which was in place until 1968—and he had an FBI file on him for obscenity, which will be elaborated on later). |

Paige McCusker | ||

| 1964 to 1968 |

I Know It When I See ItThe United States has always had some form of obscenity laws, going back as far as 1868. There were several other iterations of obscenity laws attempting to clarify the constitutionality (or lack thereof) when it comes to distributing or receiving explicit materials, but the most recent one compared to the time of the photograph is Jacobellis v. Ohio, with its famous “I know it when I see it” line of reasoning. Nico Jacobellis was the manager of the Heights Art Theater in Cleveland, Ohio, and he wanted to show the Louis Malle film The Lovers. Jacobellis was charged with two counts of possessing and exhibiting an obscene film and ordered to pay fines or spend time in jail (findlaw.com). Jacobellis appealed, having his conviction held up twice, before it reached the United States Supreme Court, where it was ruled that the film was not obscene and therefore constitutionally protected (findlaw.com). The judges, however, could not agree on one rationale. The most famous rationale is from Justice Potter Stewart, who said, “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description; and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that” (findlaw.com). This is especially notable because the FBI had an obscenity file on Warhol and his works (pghcitypaper.com). Warhol’s works were frequently avant-garde in addition to blatantly sexual, and his workers included adult film stars, drag queens, drug addicts, musicians, and more as his work and The Factory grew more popular. Lore from The Factory was that because of how frequently their works were shut down under said obscenity laws, Warhol suspected that the script for Up Your Ass, a play by Valerie Solanas, was the police trying to entrap him (archive.nytimes.com). Solanas would attempt to assassinate Warhol a year before this picture was taken, with drastic effects on his life and eventually complicating a gallbladder removal surgery (nytimes 2017). The attempted assassination would not be the end of their encounters—Solanas would repeatedly stalk him and be repeatedly institutionalized due to schizophrenia (Solanas 1966). |

Paige McCusker | ||

| 1969 |

I Want My Gay Rights Now, DarlingWarhol was also openly gay before the gay liberation movement became popular in the mid-1960s (Nickels). Much of his work focused on the relationships between gay men and other people considered to be deviants at the time (drag queens, trans women, etc.). The United States still has various homophobic laws on the books, like anti-sodomy laws that specify consensual anal and oral sex (advance.lexis.com), which are unenforceable and cannot be defined cleanly in a court of law. And as to the issue of homophobic (rules of) law, Bill Clinton would sign the Defense of Marriage Act into law in 1996, which stated that marriage was a union between “one man and one woman” and allowed states to refuse to recognize gay marriages performed in other states. This would be the status quo until it was whittled down by United States v. Windsor (2013), which declared Section 3 (defining marriage) as unconstitutional under the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment (United States v. Windsor), and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) which declared the entire text as unconstitutional under the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the 14th Amendment (Obergefell v. Hodges). There were other gay liberation movements beforehand, and the Stonewall rebellion would come only a few months before this photograph, on June 26, 1969. (June 26, 2015 was also the date that Obergefell was decided.) |

Paige McCusker | ||

| Spring 2024 to Spring 2024 |

AnalysisThis background helped me understand Richard Avedon’s work, especially as it pertains to Warhol and The Factory by contextualizing what the two have in common (different film techniques, etc.) and how Avedon’s bisexuality and Warhol’s gayness tinges their work. Both Warhol and Avedon were united in their shaping of art in the 1960s in addition to the movements of Second Wave feminism, Civil Rights, and Free Love, as well as the Cold War and Vietnam War. As for the image itself, it is actually a compilation of three different photos, like Avedon is making a collage. We see several pivotal figures in The Factory, Warhol himself notwithstanding: Paul Morrissey, who directed and acted in several films, is on the very left. By posing him on a naked actor (Joe Dallesandro) and next to another actress (Candy Darling) suggests that this is just another job to the three of them. Not to mention that displaying a trans woman’s penis and having her stare back oppositionally is very contrary to what we think of trans women. Women’s genitalia is considered widely to be taboo, and if they have a penis, disgusting. If you look at a woman with a penis and she doesn’t know, it’s fine. If you look at a woman with a penis and she looks back, it is vanity. Looking back gives someone agency. The second photograph cuts out Candy Darling save for her hair and a sliver of an arm; we see next three naked actors (Eric Emerson, Jay Johnson, and Tom Hompertz) and a leather-wearing poet (Gerard Malanga). There is commentary to make on Emerson’s bisexuality and Johnson’s brother being romantically involved with Warhol at this point, but what I want to point out is the juxtaposition of Malanga’s poetry with the leather subculture versus the naked actors effectively showing off how manly they are through a) display of their penises and b) flexing of the upper arm, in Emerson’s case. Poetry is a gender-neutral thing across the world, but in the West, if a man writes poetry and not novels, he is gay; and the leather subculture is, in many ways, hypermasculine. With Avedon choosing to put Malanga—or not making Malanga change—in leather, he is reflecting back at us our conceptions of gender and gendered activities.

Citations list: Avedon, Richard. Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, headed by Julian Bond, Atlanta, Georgia, March 23, 1963. 1963. The Work, Richard Avedon Foundation, New York City, https://www.avedonfoundation.org/the-work. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Cotter, Holland. “Richard Avedon: ‘Murals & Portraits.’” Richard Avedon - “Murals & Portraits” - NYTimes.Com, 5 July 2012, web.archive.org/web/20120707102802/www.nytimes.com/2012/07/06/arts/design/richard-avedon-murals-portraits.html. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024. “Findlaw’s United States Supreme Court Case and Opinions.” JACOBELLIS v. OHIO, 378 U.S. 184 (1964) | FindLaw, caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/378/184.html. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024. Gopnik, Blake. “Warhol’s Death: Not so Simple, after All.” The New York Times, 21 Feb. 2017, web.archive.org/web/20170222104252/www.nytimes.com/2017/02/21/arts/design/andy-warhols-death-not-so-routine-after-all.html. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024. GovInfo, 1996, www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-104publ199/html/PLAW-104publ199.htm. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Grundberg, Andy. “Richard Avedon, the Eye of Fashion, Dies at 81.” The New York Times > Arts > Richard Avedon, the Eye of Fashion, Dies at 81, 1 Oct. 2004, web.archive.org/web/20120810050450/www.nytimes.com/2004/10/01/arts/01CND-AVED.html. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024. Levine, Marty. “Film File: FBI Gives Public a Peek at Warhol ‘Obscenity’ File.” Pittsburgh City Paper, Pittsburgh City Paper, 23 June 2011, www.pghcitypaper.com/news/film-file-fbi-gives-public-a-peek-at-warhol-obscenity-file-1397581. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. “MISSISSIPI CODE OF 1972 | PAW Document Page.” Lexis®, Lexis, advance.lexis.com/documentpage/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=e055e023-912b-41fb-95f4-2de71f06d466&nodeid=ABYAAPAABABC&nodepath=%2FROOT%2FABY%2FABYAAP%2FABYAAPAAB%2FABYAAPAABABC&level=4&haschildren=&populated=false&title=%C2%A7%2B97-29-59.%2BUnnatural%2Bintercourse.&indicator=true&config=00JABhZDIzMTViZS04NjcxLTQ1MDItOTllOS03MDg0ZTQxYzU4ZTQKAFBvZENhdGFsb2f8inKxYiqNVSihJeNKRlUp&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fstatutes-legislation%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A8P6B-8B52-8T6X-73W5-00008-00&ecomp=7gf5kkk&prid=f61ff3ec-3068-4194-994f-f0e7ce32c270. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024. Nickels, Thom. “Out in History : Collected Essays : Nickels, Thom : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, Sarasota, FL : Starbooks Press, 2005, archive.org/details/outinhistorycoll0000nick/page/22/mode/2up?view=theater. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "Gay Liberation Front march on Times Square" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1969. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/956a5f00-264d-0137-1a15-21e4cc4ff485. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Marshall, Rick. “Obscenity Case Files: Jacobellis v. Ohio (‘I Know It When I See It’).” Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, cbldf.org/about-us/case-files/obscenity-case-files/obscenity-case-files-jacobellis-v-ohio-i-know-it-when-i-see-it/. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. “Richard Avedon: Murals.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023, www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/richard-avedon-murals. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. “The Work.” The Richard Avedon Foundation, www.avedonfoundation.org/the-work. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Scalia, Antonin, Anthony Kennedy, et al. “United States v. Windsor Decision : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, Oct. 2012, archive.org/details/717814-united-states-v-windsor-decision. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Scalia, Antonin, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, et al. “Obergefell v. Hodges - Supreme Court.” Wayback Machine, Oct. 2014, web.archive.org/web/20160610201120/https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/14-556_3204.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Solanas, Valerie. SCUM Manifesto. V. Solanas, 1967. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. |

Paige McCusker |