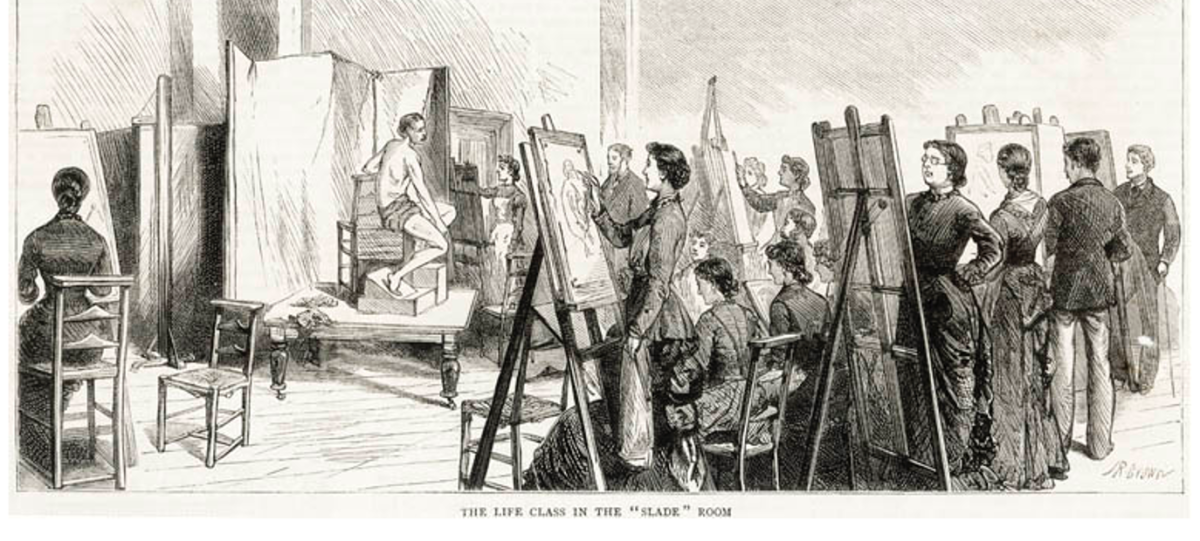

In the traditional art education system of Victorian England, female artists were predisposed for failure. Two of the founders of the Royal Academy of Arts, Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffman, wouldn’t have been allowed to study in the school they helped build until nearly a century after its establishment, when in 1860, the Academy admitted their first female artist entirely on accident; Laura Herford sent in a drawing to the school with only her initials on it and was accepted before anyone could figure out that she wasn’t a man. Large, private academies like the RAA effectively “othered” women out of success by separating them from the men, barring them from any high-level teaching positions, and not granting them access to the live nude models men were sketching regularly. While the standard of separation by sex was motivated by a desire to maintain and protect men’s place in the art world, it pushed women to open and attend their own art schools where they controlled the curriculum, wages, and staff, and ultimately enjoyed a level of autonomy that could not have been achieved within the academy system (Quirk)

Many women abandoned the rigid English academic art system for the smaller, more progressive schools in Paris, where they could experience a more individualized education by enrolling in ateliers. The atelier system, which evolved out of the structure of apprenticeships during the 17th century, prioritized the relationship between one artist, who functioned as a mentor, and the student, who focused on developing their own marketable style as opposed to copying the classics. Prominent Victorian artist Louise Jopling became a student of atelier Charles Chaplin in the 1860’s, where she experienced an all-female classroom, and had access to nude models. Jopling opened her own atelier many years later, named “Mrs. Jopling’s School of Art”; following in the footsteps of Chaplin, she opened her doors to women only, where, in her words, "careful mothers could send their daughters… without complications between the sexes” (Quirk 40). Other female British ateliers include Henrietta Ward, who came from an upper-class family of artists and opened her all-female school in 1879, as well as Elizabeth Armstrong Forbes, who opened the mixed-gender Newlyn School in the 1880’s with her husband Stanhope Forbes (Quirk). While Jopling, Ward, and other ateliers who followed the all-female framework played into the existing separation of the sexes in formal art education, creating a space purposefully dominated by women allowed the students the freedom of joining an equitable artistic community without fear of prejudgment. Additionally, women who owned art schools had a degree of economic freedom and artistic influence that had previously been unattainable within the male-dominated world of fine art and extended the privilege to other women by hiring them as teachers or experts (Quirk). These environments proved to be incredibly nurturing for female artists; a journalist who visited the Jopling school in 1893 described the artist as a “guide, philosopher, and friend” to her “earnest” students, who looked to Jopling with “loving respect and reverence” (Quirk 41).

While female-run atelier-style schools became the British norm for the upper-class female artist, the reality of art education was further separated by status. Middle and upper-class women had the time and luxury of studying at ateliers or schools of fine art, like the RAA or the Female School of Design, while members of the lower classes attended technical colleges, like the Central Training School and Birmingham Branch Schools, with the goal of becoming specialized artisans. Interestingly, women who studied fine art were often seen as inferior to their counterparts who studied the decorative arts. Fine arts like painting and sculpture were considered masculine, while applied art like embroidery or furniture making were considered traditionally feminine. Upper class women who attended fine art schools within the academy system experienced a higher degree of segregation than those who attended decorative or applied art colleges, where men and women often attended class side by side. Within the technical colleges themselves, however, there were divisions based on sex; women were relegated to role of “designer or decorator”, while men were the “executors of furniture, pottery, and handiwork” (Zimmerman 114). As a result, men were given the opportunity to specialize in higher-paying roles, while women were placed in subordinate positions. This discrimination did not detract from the fact that artisanship was one of the only careers that a lower- or middle-class woman could viably attain outside of housework or hard labor (Zimmerman).

The Woman’s Gazette; Or, News About Work, a publication aimed at lower class women, featured a weekly section that concentrated on advice on how to break into the industrial arts, and published paid work opportunities in its directory. The Gazette continuously published praise for women’s achievements in art shows and reminded their readers of deadlines to submit to art schools like the Bristol Fine Arts Academy, the Glasgow Institute of Fine Art, and other technical colleges like the Ladies Dressmaking Association. Publications aimed at middle and lower-class women like The Woman’s Gazette, the English Woman’s Journal, and the Englishwoman’s Review have at times been held responsible for the class divide between fine art and applied art due to the fact that they encourage women to obtain education in the decorative arts. In reality, the purpose of these publications was to help women enter the workforce, and the decorative arts, where women were more likely to attain gainful employment, provided more economic opportunity for their readers (Devereux).

In the later part of the Victorian era, women had come so far in their access to formal art education that they were able to critique their options, when less than 50 years earlier, the goal was to simply be allowed to enter the building. In the later part of the 19th century, women created educational opportunities for themselves through the atelier system and technical colleges, allowing them to solidify a new generation of upwardly mobile female artists who were able to support themselves financially – a huge step towards feminine independence overall.

WORKS CITED

Devereux, Jo. "The Evolution of Victorian Women's Art Education, 1858–1900: Access and Legitimacy in Women's Periodicals." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 50 no. 4, 2017, p. 752-768. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vpr.2017.0054.

Quirk, Maria. “An Art School of Their Own: Women's Ateliers in England, 1880–1920.” Woman's Art Journal, vol. 34, no. 2, 2013, pp. 39–44. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24395310.

Zimmerman, Enid. “Art Education for Women in England from 1890-1910 as Reflected in the Victorian Periodical Press and Current Feminist Histories of Art Education.” Studies in Art Education, vol. 32, no. 2, 1991, pp. 105–116. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1320282.

IMAGES

Image 1: A life class at the Slade (1881)

Image 2: A life class for female art students, Paris. (1894)

Courtsey of https://www.maryevans.com/tales.php?post_id=15482