This exhibit explores the nature of letter writing in the Regency era as it shows up in Jane Austen's novels and in her own life as a writer who had an extensive, intimate correspondence with her older sister, Cassandra, throughout her life, writing thousands of letters before her untimely death at the age of 41 in July 1817. Austen also uses letters as an integral part of her storytelling, often granting her characters moments of brief or long monologues to express themselves more openly and sometimes, more vulnerably. In this exhibit I use the letter Fanny Price writes to Mary Crawford, which is a very short yet effective letter, where she addresses her proposed attachment to Henry Crawford as a vehicle to discover the necessity for verbal economy and precision in letter writing. I also consider how the pratical elements of letter writing—from the written words to the seal—impacted the nature of these letters, too, and compare it with our own modern forms of communication today.

Fanny Price's Letter to Mary Crawford, Volume II, Chapter XII, Mansfield Park (1814), by Jane Austen. In this letter in Jane Austen's Mansfield Park (1814), Fanny Price manages to do something we've all struggled to do at least once in our own lives—write an extremely direct letter of rejection that still manages to read as kind and respectful. Fanny Price is indeed the master of manners and poise, managing to convey utmost consideration of Miss Mary Crawford's feelings, whilst still standing her ground and firmly disgareeing with her proposition for attachment to her brother, Henry Crawford. I chose this letter because not only is it short and concise, which is a skill I lack in my own writing, but I also felt that there is potential for instruction and encouragement when it comes to learning how to grow a backbone without shrinking someone else's in the process.

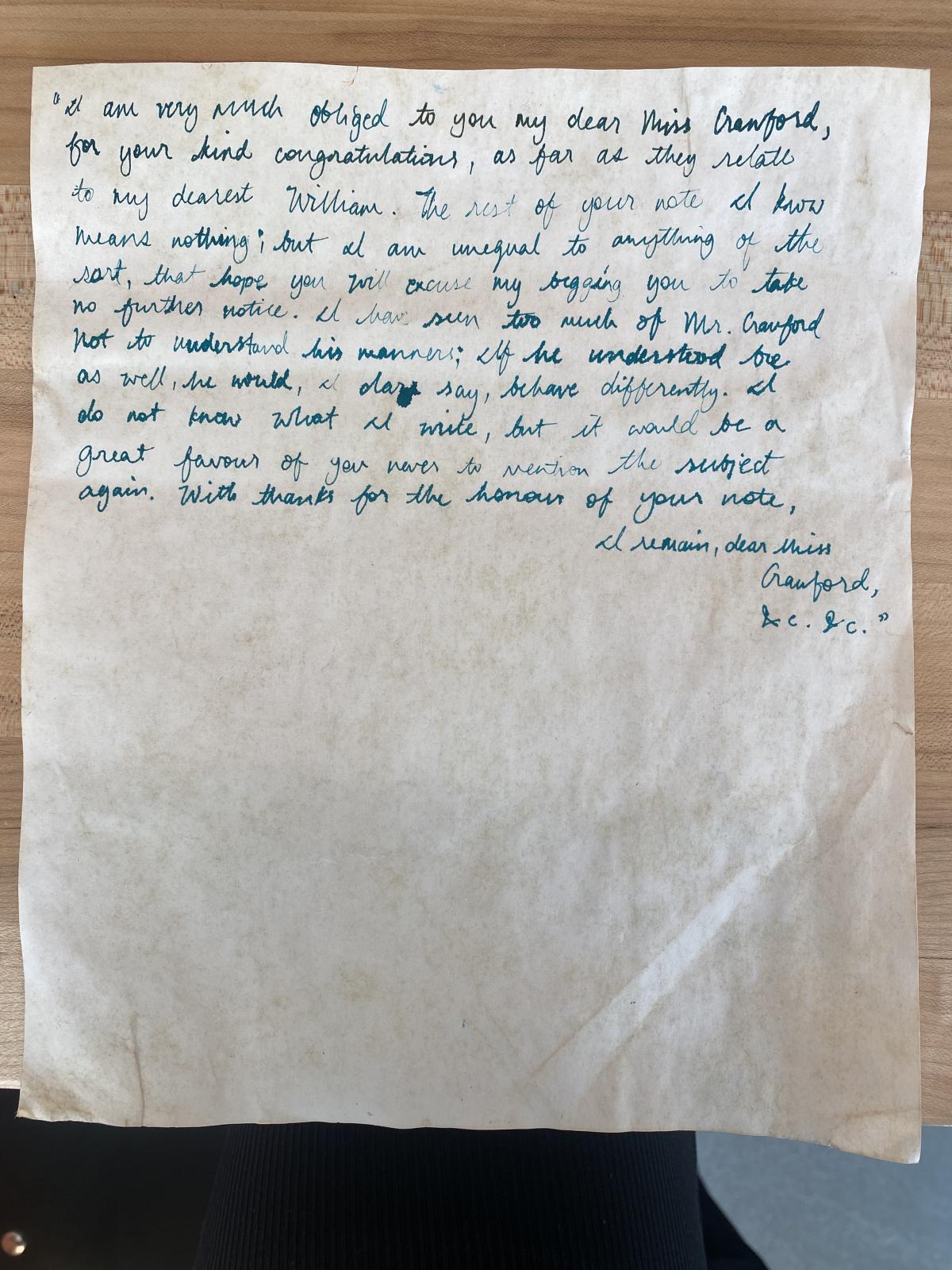

Recreation of Fanny Price's Letter to Mary Crawford, Volume II, Chapter XII, Mansfield Park (1814), by Jane Austen, crafted by Anesu Mukombiwa, 2023. As I wrote out these five sentences, I found the process of cautiously and painstakingly trying to make sure each word was unsmudged and legible made apparent to me the level of intentionality that must have gone into all letters during the Regency period. I realized that with the pace and caution I was using to write this letter, every word was far more interior, each phrase essential and indispensible. Although I must factor in my own lack of experience and dexterity, since many of the people that were educated enough to write letters during this time had gotten ample practice, I cannot imagine creating this careful craft of ink absentmindedly or insincerely. This exercise revealed to me that letters—writing them, receiving them—really mattered because of the effort and time that they required. The contrast with other versions of communications that have since replaced letter writing is so jarring. Today, shooting a text is easy, pain free, and often done with the slightest sincerity because there need not be any time or concentration sacrificed to perform the task. I wonder how differently we might have expressed ourselves, or how different the depth of our friendships and realtionships might have been, if we were still in the habit of writing them letters instead of sending them three word text messages. R U OK? There is also an element of intimacy that came with letter writing, particularly because the words were literally sent miles and miles away to be held and tocuhed by the person who could have been on the other end of the world, which probably yielded much weightier correspondence. Nowadays, a text message can easily turn into a screenshot and instantly those words become shareable with anyone else who has a smart phone, which I imagine has affected the nature of our conversations considerably.

Folded and addressed letter to Mary Crawford, Volume II, Chapter XII, Mansfield Park (1814). After finally managing to write out a draft of the letter that was nearly perfect, I folded and addressed it as pictured above. I thought the final product was quite neat and had a certain degree of romance to it; there was something about being able to tuck these words into themselves and present them as an openable gift for someone else that really heightened the romance of it all for me. But I knew that this alone could not have been the allure for the letter folding practice during the Regency era, so after doing further reaserch, I learned that it actually had more to do with the cost of the whole letter sending process. It was a very expensive exercise. Various factors affected the cost of posting a letter, including the distance (how far it was being posted), the weight of the letter (if anything was enclosed), and whether it was a single or double sheet. If the latter occurred, the cost of your letter would be doubled. To keep costs down, the method of folding the letter into itself and writing the address on the outside of the same sheet became a popular and inexpensive way to keep up this custom. Far less romantic but still very interesting!

Sealing the letter with red wax seal. After folding and addressing this letter, I proceeded to seal it with red wax and a sealing stamp provided by Dr. Golden, which left a beautiful flower decoration pressed into the wax. The process of sealing the letter was exciting because it drew my attention to the question of privacy and intimacy in the letter writing process, which I had not considered before. I was inclined to think of Jane Austen's own letters and the fact that we have access to them now posthumously. Those letters she wrote to her loved ones—letters she probably sent out with a seal to protect her privacy and the privacy of the recipients—are now being widely distrubuted and read after her death and without her consent, which makes me wonder about the ethical considerations of publishing famous people's private letters for public consumption. But perhaps that is precisely why we are so enamoured by these letters, because we are aware of our allowance into something that was intended only for one person's eyes. This protection of privacy wasn't the sole factor, however, that made the sealing of letters so imperative; sometimes the wax was even used to hide a coin to pay the postman (thereby costing the recipient nothing; postage was originally paid by the receiver) and also to identify the sender, as people maintained personal and family seals for this purpose.