Editorial Introduction to "The Harlot's House"

Oscar Fingal O’Flaherty Wills Wilde (1854-1900) was born in Dublin, Ireland to Jane Francesca Agnes Wilde (nee Elgee) and William Robert Wills Wilde. Wilde’s father published books on Irish folk history, archaeology, and medicine, and was recognized for his work as an ear and eye surgeon. His mother was a spirited poet who wrote under the name of Speranza. An avid collector of Irish folklore, she was strongly invested in the Irish nationalist movement. She was also a linguist and a stringent advocate for women’s rights regarding issues such as equal education and property ownership.

At the Portora Royal School at Enniskillen and then Trinity College in Dublin, Wilde excelled in classics. This continued during his studies at Magdalen College at the University of Oxford. Here he received his first major success as a poet, winning the Newdigate Prize in 1878 for his poem “Ravenna.” After university, he moved to London, where he published a collection entitled Poems in 1881 to a lacklustre reception. The work saw three editions within its first year, but Ian Small points out that publishers often put out and promoted a “new” edition by simply using first-edition copies that had not sold. This strategy, intended to suggest falsely a work’s popularity and thereby to stimulate sales, was used with Wilde’s Poems (xv). An actual new edition of Poems with some textual revisions did not appear until 1892. It was published by the Bodley Head as an example of the book beautiful and was a financial success. Wilde never published a book of poetry other than Poems.

Fortunately, in the early 1880s, Wilde’s public persona as the spokesperson of the Aesthetic Movement in British literature, art, and domestic culture (Gagnier) had caught the attention of the talent agent Richard D’Oyly Carte. As the founder of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, he sent Wilde on a North American lecture tour where he presented himself as a dandy-aesthete, directly building on the success D’oyle Carte’s production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience, or Bunthorne’s Bride. The comic opera, first performed on 23 April 1881, was in part a send-up of the popular cultural persona of the dandy-aesthete, and was not targeted at Wilde or any other individual. It would be more accurate to say that Wilde’s own image and his success as an author benefitted from Patience, rather than the other way around. Agreeing to wear the costume and maintain the character of the dandy-aesthete during his tour, Wilde lectured primarily on aspects of the Aesthetic Movement, although he also spoke on “Irish Poets and Poetry in the Nineteenth Century” (Cooper).

This particular moment in Wilde’s career is captured in William Powell Frith’s painting A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881 (1883). Among the crowd of tasteful Londoners Frith includes an image of Wilde with long locks and a lily (a symbol of the aesthetes) in his lapel. He is surrounded by women and a boy in a velvet coat and knickerbockers reminiscent of those Wilde was depicted wearing during his North American tour. The inclusion of the youth in the painting alludes to growing anxieties around the influence of Aestheticism and Decadence on young men in British society.

The figure of the dandy-aesthete was a sexually loaded one at this time. For Alan Sinfield, the flamboyance and effeminacy of the persona did not signify same-sex desires, but rather heterosexual male’s promiscuity. It is more accurate to recognize, more generally, that the men’s ambiguous investments in secretive, noncommittal dalliances evoked the possibilities of some sorts of nonnormative sexual relations. Infidelity, frequenting brothels, sleeping with other men – these were all recognized as possibilities. With the technology of marginalization operating in a similar fashion for each type of indiscretion, the very uncertainty was part of the persona’s allure and a source of cultural unease.

Wilde himself evokes this model of secrecy and sexual anxiety in comments published in the Pall Mall Gazette during a witty back-and-forth between himself and the homosexual poet Marc André Raffalovich regarding the correct number of syllables in the word “tuberose.” Discussing the etymology of the flower, Wilde argues that poets should “dwell on the tiny trumpets of ivory into which the white flower breaks, and leave to the man of science horrid allusions to its supposed lumpiness and indiscreet revelations of its private life below ground” (“Parnassus”). The aim of art of any form, then, is to stimulate the senses without revealing the artist’s own private sources. “The Harlot’s House,” published less than two weeks later, in April 1885 in the Dramatic Review, explores the same principle as a social dictum.

Curiously, the publication history of “The Harlot’s House” was unclear to many in Wilde’s own time (Thomas). A draft version of portions of “The Harlot’s House,” written in Wilde’s hand and dated April 1882, can be found at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. The version he finally published was most likely written in the Spring of 1883 when he was in Paris (Sherard, 31). The following year, Wilde wrote the editors of the Dramatic Review, “If you would like a poem I will send you one,” adding that he would prefer to see it published in an issue that had no other poetry and in particular no parodies of any poets’ work (qtd. In Stokes 42). As John Stokes notes, he also gave instructions for its layout – asking for substantial margins and only one column, thereby creating a bold and unique setting for the piece. After its publication in the Dramatic Review on 11 April 1885, it was not publically published again until it was added to the reprint of Poems in 1908.

The casualness of his initial offer and the specificity of his layout suggestions belie just how seriously Wilde would have wanted to see his work published. Poems had not established his name and his lecture tour had been a couple of years back. In the meantime, he and Constance Lloyd had married, so a steady income and solidified reputation were all the more important. While Wilde was steadily publishing individual poems throughout the 1880s, he also turned to writing arch reviews and commentaries for a selection of periodicals, with his investment in theatre particularly apparent in material written for the Dramatic Review from 1885 to 1887.

“The Harlot’s House” warrants consideration as an example of what might be called a theatre-poem, inspired perhaps by the new genre of the prose-poem of particular interest to the Decadents and Symbolists whom Wilde admired. By the mid-1880s, he had enmeshed himself in the theatre community – a culture of cosmopolitan nightlife that permeates the theme and imagery of the poem. Moreover, the poem’s overall sense of artifice and its emphasis on the performance of the characters (“dancing feet,” “musicians play,” “clockwork puppet,” etc.) evoke the stage and its orchestra pit. The motif of music and rhythm is further reinforced by Wilde’s use of consonance and a somewhat pounding iambic tetrameter.

“The Harlot’s House” is most centrally a poem about prostitution, but it is not heavy-handed in its position on the subject. The emphasis on façades, silhouettes, performance, and darkness work to aestheticize the subject, giving it an allure that shifts the imaginative experience of the reader to one of personal pleasures, and makes the privacy of desire itself the main topic of engagement. That said, the language of automata, marionettes, and dancing dead does encourage a moral stance against the dehumanizing influence of prostitution. Since Théophile Gautier’s assertion in his preface to Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835) that art exists only for the realm of art itself and not for other, external measures of value, authors and artists from around the world, including Wilde, have offered variations on the theme. Despite this emphasis on art’s liberty from responsibility, it was common among these authors and artists to remain ambiguous around issues of morality, often allowing for more conventional readings of their work.

Prostitution was a crucial social issue at this time. In articles later collected as London Labour and the London Poor (1862), Henry Mayhew had not much earlier made it clear just how common and even necessary the mode of employment was for the British economy. One is taken by the casualness with which the subject of prostitution is discussed among those Mayhew interviewed, although the words, at best paraphrased from recollection of conversations, are Mayhew’s own. One 20-year-old that he describes in detail for her beauty, says “I was walking along the Strand looking out for my living by prostitution – I wouldn’t starve” (463). A young man, meanwhile, notes that women often turned to prostitution for income for themselves and their partners: “I did know two that kept young men, their partners, going about the county with them, chiefly by their stealing. Some do so by their prostitution. Those that go as partners are all prostitutes” (403). The Contagious Diseases Acts of 1864, 1866, and 1869 – notorious for criminalizing female prostitutes but not the men who purchased their services – met with a major social outcry. Many recognized the gendered double-standard and, after sustained, organized protest rallies and lectures, the laws were repealed in 1886, the year after “The Harlot’s House” was published. As Wilde’s image of the harlot as a marionette suggests, the contemporary prostitute was seen as virtually never driven by her own agency. And the image in his final stanza of the dawn as it, “with silver-sandalled feet, / Crept like a frightened girl” reflects how very young many London prostitutes were. This closing image of an injured innocent gains emphasis by tripping on the metre, as it suddenly shifts from a consistent four iambs to three.

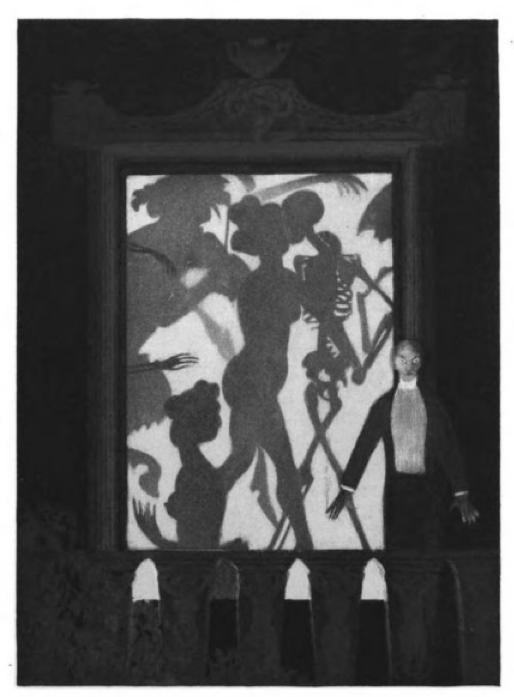

On 13 June 1885, two months after “The Harlot’s House” was published, a parody entitled “The Public-House,” appeared in the Sporting Times, signed “Tramway Tame” (a play on “Oscar Wilde”). Leonard Smithers, who felt the original was Wilde’s “finest and most imaginative Poem” (7), published it on its own in a 1904 edition (under the alias of the Mathurin Press). It included five monochrome illustrations by the highly respected Irish artist Althea Gyles (Fig. 1), of which Smithers claimed Wilde approved. There is no verification that Wilde approved of the images or the edition, but Wilde, Smithers, and Gyles had discussed the publication in Paris in 1899 (Nelson 268). Alfred Douglas states that he put up some of the money for the publication, noting his own admiration for Gyles’s work (145)

Figure 1: Althea Gyles, “Sometimes a horrible Marionette / Came out and smoked a cigarette.” The Harlot’s House. n.p.

In accord with “The Harlot’s House” itself, Gyles’s images combine the theatricality of the poem with a Danse Macabre, a reading that encourages one not to judge the prostitutes more harshly than oneself. The illustrations are also suggestive of Aubrey Beardsley’s three black-and-white drawings “The Comedy Ballet of Marionnettes,” published in The Yellow Book in 1894, both works presenting the images in a stage-setting, in black and white, with strong erotic over-tones and an ambiguous narrative structure. When, in “The Harlot’s House,” Wilde writes “Like wire-pulled automatons, / Slim silhouetted skeletons / Went sidling through the slow quadrille,” it is not only the prostitutes he portrays as death, a suggestion Gyles picked up on.

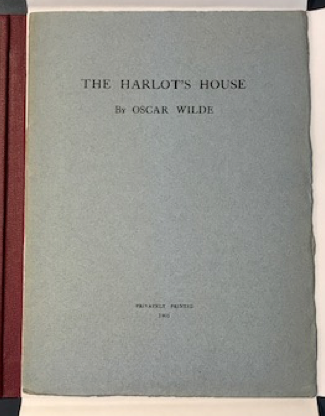

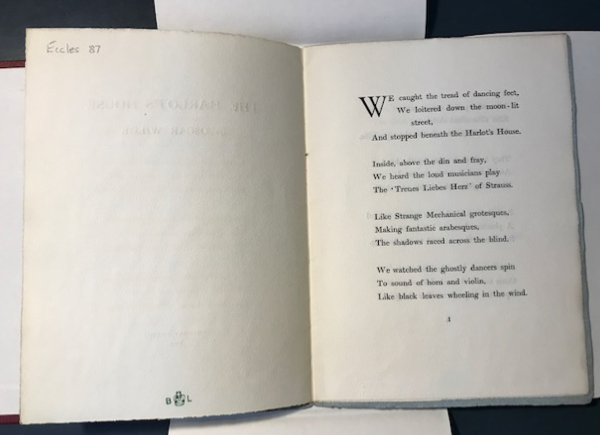

Another privately printed facsimile appeared as an 8-page pamphlet in 1905 (see Figs. 2 and 3). The same year, an untitled version appears in Reynold’s Newspaper and another in the Mosher Press’s U.S. edition of Poems (Mason 57-58). Throughout the twentieth century to the present day, the poem has continued to appear either as an individual book or in publications of Wilde’s work and other broader collections. A particularly unique and very limited, letter-press edition appeared for the Christmas market in 1967. It included silhouettes created by blowing colored aerosol paint through lino-cuts based on drawings by the artist Daphne Lord.

Figures 2 and 3: Privately printed facsimile of “The Harlot’s House” (1905): outer cover and first page of the poem (with preceding page).

The version of “The Harlot’s House” that we reproduce here is based on its first publication in 1885 in the Dramatic Review. This virtual edition has been edited by a team of seven Wilde scholars for COVE online. Key subjects of this first set of annotations include: editions and revisions; existing scholarly commentary; sex and sexuality; dance, theatre, and performance; and French influences. The intention of this initial publication and set of annotations is to establish the poem’s editorial history, offer selected links to materials in diverse media (including visual art and performance videos), and to suggest a range of thematic approaches to the work that would encourage diverse analyses. In addition, we hope that the edition will inspire users of the editorial tools to offer alternative themes, methodologies, translations, and archival materials, and analyses, and to situate the poem within other cultural contexts, perhaps especially aiding professional translators. (We are currently working with two Chinese translations. See Fig. 4.) In this way, as additional Decadent and Aesthetic texts are added to COVE online, the project will foster a virtual, scholarly community, allowing the poem to live in a public forum – just as Wilde’s famous public persona continues to be constructed in large part by an audience of invested admirers.

Figure 4: Wilde, Oscar. A Complete Collection of Wilde’s Works. Vol. 3: Poetry. Beijing: Chinese Literature P, 2000. This volume contains the translation of “The Harlot’s House” by Qiu Ke’an (裘克安) on pages 160-62.

Works Cited

Beardsley, Aubrey. “The Comedy Ballet of Marionnettes.” The Yellow Book. Vol. II (July 1894): pp. 87, 89, and 91.

Cooper, John. Oscar Wilde in America: A selected Resource of Oscar Wilde’s Visits to America. Accessed: 4 Jan. 2018.

Douglas, Alfred. Oscar Wilde and Myself. New York: Duffield, 1914.

Frith, William Powell. A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881, 1883, oil on canvas, private collection.

Gagnier, Regenia. Idylls of the Marketplace: Oscar Wilde and the Victorian Public. Palo Alto: Stanford UP, 1986.

Mason, Stuart. Bibliography of Oscar Wilde. London: T. Werner Laurie, 1914.

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor. Vol. 3. London: Griffin, Bohn, and Company, 1861.

Nelson, James G. Publisher to the Decadents: Leonard Smithers in the careers of Beardsley, Wilde, Downson. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2000.

Sherard, Robert Harborough. Oscar Wilde: Story of an Unhappy Friendship. London: Greening, 1905.

Sinfield, Alan. The Wilde Century. London: Cassell, 1994.

Small, Ian. Introduction. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000.

Smithers, Leonard. “Prefatory Note.” The Harlot’s House. London: Mathurin, 1904.

Stokes, John. “Wilde’s World: Oscar Wilde and Theatrical Journalism in the 1880s.” Wilde Writings: Contextual Conditions. Ed. Joseph Bristow. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2003. pp. 41-58.

Thomas, J.D. “The Composition of Wilde’s ‘The Harlot’s House’.” Modern Language Notes. 65.7 (Nov. 1950): 485-88.

“Tramway Tame.” “A Public-House.” The Sporting Times. 1134 (13 June 1885): 7.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Harlot’s House.” Dramatic Review. 1.11 (11 April 1885): 167.

---. The Harlot’s House. 1885. London: Mathurin, 1904.

---. The Harlot’s House. 1885. Richmond, UK: Keepsake, 1967.

---. “Parnassus versus Philology.” Pall Mall Gazette. XLI.6257 (1 April 1885): 6.

---. Poems. London: David Bouge, 1881.

---. Poems. London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane, 1892

Selected Additional Works

Beckson, Karl, and Bobby Fong. “Wilde as Poet.” The Cambridge Companion to Oscar Wilde. Ed. Peter Raby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. pp. 57-68.

Boyiopoulos, Kostas. The Decadent Image: The Poetry of Wilde, Symons, and Downson. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

Bristow, Joseph. Oscar Wilde on Trial: The Criminal Proceedings, from Arrest to Imprisonment—5 April 1895-25 May 1895. New Haven, CT: Yale UP. Forthcoming.

---. “Oscar Wilde’s Poetic Traditions: from Aristophanes’s Clouds to Ballad of Reading Gaol.” Oscar Wilde in Context. Ed. Kerry Powell and Peter Raby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013. pp. 73-87.

Davies, Helen. Gender and Ventriloquism in Victorian and Neo-Victorian Fiction: Passionate Puppets. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2012.

Dellamora, Richard. Masculine Desire: The Sexual Politics of Victorian Aestheticism. Chapel Hill, NC: U North Carolina P, 1990.

Denisoff, Dennis. “Sexuality.” Victorian Studies. 1998. Forthcoming.

Dollimore, Jonathan. Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991.

Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. New York: Knopf, 1987.

Fehr, Bernhard, “Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Harlot’s House’.” Archiv für das Studium der Neueren Sprachen und Literaturen. 134 (1916): 59-75.

Fong, Bobby. “Wilde’s ‘The Harlot’s House’.” The Explicator. 48 (Spring 1990): 198-201.

Fryer, Jonathan. Wilde. London: Haus, 2005.

Gagnier, Regenia. “The Global Literatures of Decadence.” The Fin-de-Siècle World. Ed. Roger Saler. London: Routledge, 2015: 11-28.

Holland, Vyvyan Beresford. Oscar Wilde: A Pictorial Biography. New York: Viking, 1960.

Hyde, H. Montgomery. Oscar Wilde: A Biography. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1975.

McCarren, Felicia M. Dancing Machines: Choreographies of the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2003.

Mustafa, Jamil. “Haunting ‘The Harlot’s House.’” Wilde’s Worlds: Oscar Wilde in International Contexts. Ed. Michael Davis and Petra Dierkes-Thrun. London: Routledge, 2018. Forthcoming.

Quinn, Justin. “Irish Poetry in the Victorian Age.” The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Poetry. Ed. Matthew Bevis. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013. pp. 783-99.

Roditi, Edouard. Oscar Wilde. New York: New Directions, 1986.

Sherard, Robert Harborough. Bernard Shaw, Frank Harris & Oscar Wilde. New York: Greystone, 1937.

---. The Life of Oscar Wilde. New York: Brentano’s, 1911.