A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by

Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER XXXI.

A TRIAL FOR LIFE.

Was that poor belated soul, struggling between the temporary oblivion of sleep and the desire to be up and doing, strong and vital in its energy to fight the great fight of existence?

How could so many incidents of real life be crowded into so small a space, and yet be actual?

How could he, Captain Weed Markham, an officer of the king's guard, the bearer of that royal ring which was a passport to the presence of regality, the apparent friend, counsellor, and confidant of a monarch, he now so utterly stricken down?

Could it indeed be real?

Had he not fallen asleep in some of the corridors of St. James's dreaming of the old precept, "Put not your trust in princes" and so built up an airy fabric of imaginary dangers?

Or did he lie and dream uneasily beneath the dilapidated roof of old Whitehall? Or in that mysterious house at Westminster which had been given to the flames? Or at the palace at Kew? Or in his own familiar chamber in the barracks adjoining?

Was it all a dream?

Was there no secret service required of him?—no Mystery in Scarlet shot to death through that terrible curtain?—no state secret whispered into his ears, each word of which was worth a thousand lives?—no rescue of that young fair girl whose Paladin of romance he had become?

Awake, awake, Weed Markham! Perchance it is all a dream, a something to recount to your brother officers over their watch-fire, a something dim, intangible, crowded with busy incident, and a mystery of the imagination for over and for ever.

No, it is too real.

He feels the smart of slight wounds.

He feels the aching of the muscles after unwonted exertions.

It is too real.

He is awake, and it has all happened.

He has flung away a life—flung it away heedlessly and recklessly, as a gambler plays with the only coin in his purse, and in losing it he has surely lost more than all; for what now is to become of that other young life so wound up in his, so dependent on him?

No, no, it were madness to struggle again.

The one terrible effort he had made for freedom had not been for his own sake, but for hers.

It was the thought of Bertha's desolation which had nearly driven him mad.

But something of a soldier's instinct now keeps him quiet, for the yeomen of the guard have been displaced by a Sergeant's guard of his own regiment.

"Recover arms! Shoulder arms! Slope arms! March!"

Markham obeyed the order.

Tramp, tramp, tramp. It was an awful march that.

Once only he paused, for his heart was very full—paused for a moment, and lifted his hand above his head, as though he were about to speak; but he suppressed and beat down the accents of his own voice, and fell again into the marching steps of the soldiers.

And yet there was so much he wished to say that he had left unsaid—so much that he could have upbraided the king with—such bitter, scathing, scorching words that he could have uttered.

Too late! It is too late now. The treacherous heart of that at once feeble and vindictive monarch has triumphed. His knowledge of men has been alone searched for in his own breast, and he trusts no one, because he feels that he himself is treacherous.

Yes, it is too late now. Captain Markham is in the toils. he has played with a king and has lost the game.

Yet why should he lose it? What has he done?

Why should he be forced to play such a game? Has he not drifted—merely drifted, like some atom upborne by a strong current—into his present circumstances?

And was he not drifting still —drifting to death?

It was very hard, very sad, calamitous, and woful—difficult to bear—very, very bitter.

He had not fallen from some mad clutch at aggrandisement placed at some height beyond his reach.

No scheme of wild ambition, dazing the senses and bewildering the imagination, had brought all this despair and danger upon him.

No. He was a pure victim—a victim to others' passions, to others' fears—a victim to that craft of statesmanship which makes such kings as that then living gracious one of England play with lives as they do with pawns on a chessboard.

"Halt!"

Captain Markham started. In the dim confusion of his mind he had not noticed whither the guard were conducting him, but that word "Halt!" recalled him somewhat to himself.

"Captain, you will be so good as to say if you have any arms concealed about you."

It was the sergeant of the guard who spoke.

"I have none, sergeant. You perceive that my sword is no longer in my own possession."

"I see it, captain, and the more's the pity."

"Ah! you pity me?"

The sergeant looked a little alarmed.

"I am afraid I am exceeding my duty, captain, which is simply to leave you here with a sentinel."

Markham glanced around him.

He knew the place then.

It was a gloomy kind of chamber, with very old oak panellings and a groined ceiling, from the centre of which hung a rusty iron lamp, certainly not fed with the most savoury smelling oil in the world.

In fact, the place was used as a temporary military prison, into which any soldier might be thrust at the will of his commanding officer for any breach of the punctilios of military discipline.

"You will do your duty, sergeant," said Captain Markham after a pause, for he saw the look of indecision and distress that was upon the countenance of the soldier.

"Thank you, captain, thank you."

The sergeant glanced about him, and then called out in resolute tones—

p. 162

"Number ninety-seven!"

"Here!" replied one of the guard, in the short abrupt tone usually used on parade under inspection.

"You will keep close guard over this prisoner; you will permit no persons to approach him by word, look, or letter; you will see that he does no injury to himself; and you will repeat these orders to the sentinel who will relieve you in due course. Right about face! "March!"

The sentinel "carried arms" and commenced a monotonous march to and fro in that dreary apartment.

"Atkins," said Captain Markham. "Don't, sir, don't. I mustn't."

"In the orders that were given you there was nothing to prohibit you speaking to me."

The soldier paused in his monotonous march.

"Wasn't there, captain?"

"No, Atkins, as you yourself must well recollect."

"Well, captain, Í don't think there was; but I take it it's rather against the ordinary code of rules for sentinels—rule thirty-two, section nine. 'When on guard over any prisoner, military or civil, you are by no means to engage in conversation with any such prisoner, and to do so is contrary to all military discipline.'"

"Never mind, Atkins. It may be that my hours are numbered in this world, and there are times when we must all remember we are men as well as soldiers."

"I can't help you speaking, captain, but I mustn't answer. Go on, sir."

"Atkins, I have been betrayed here to my death. I have done nothing, thought nothing, dreamed of nothing which could be construed into an offence."

Atkins looked a little puzzled.

"I'm a plain simple fellow, sir, and don't quite understand you."

"True, true. My good fellow, I am accused of something which I never did."

"That's just like me, sir. Four-and-twenty hours in the black hole and a week's extra drill for something I never did. I don't mean to say but I ought to have done it, sir, but I didn't, I quite forgot it, and that's all about it."

"You mistake, Atkins. I am accused of an overt act."

"I'm no scholard, sir. What may that be?"

Markham despaired of making Atkins understand him, but he made yet another effort.

"They want to make out, Atkins, that I drew my sword on the king."

"Do they, captain?"

"Yes. But I did no such thing."

"Then how can they make it out, sir? It's all very well for a poor fellow like me to be had up before my adjutant for something I didn't do, because if I say I didn't it's called pertinence and bordination, and into the black hole I goes. But you're an officer, sir, and that makes the difference."

"Nevertheless, Atkins, the king will say I did this thing."

"The king, captain?"

"Yes, the king."

"Well, but captain, why? why? why?"

"My poor fellow, if I were to tell you, really your life would not be worth four-and-twenty hours' purchase. No!" exclaimed Markham, as he now seemed to forget for a few moments the presence of the sentinel, and paced the dreary room with rapid strides. "No! This dreadful secret shall destroy no more men. I will not perpetuate its blighting influence. This death-warrant shall not pass from hand to hand through my instrumentality. There are already two victims; let them suffice—let them suffice."

"But, captain—"

"Oh! Atkins, I forgot you. And, my good fellow, you must, and I feel that you will, do me a service."

Atkins shook his head.

"I'm a poor fellow, sir, and—"

"You shall be a poor fellow no longer. You can purchase your discharge for thirty guineas. Here is what I think will provide you with that sum four times over."

"What is it, sir?"

"A diamond."

The soldier shook his head.

"It's no use, sir. They'd say I stole it."

Captain Markham held one of the glittering gems in his hand which he had brought from Whitehall, and he felt the full truth of what the poor soldier said.

A few crown-pieces would have been a much more effectual bribe to number 97, full private in his Majesty's Coldstream Guards, than a brilliant perhaps worth really a couple of hundred guineas.

"Here, then," said Markham, "here is some current coin, and what I want you to do, Atkins, is just this—let me, by some means or another, have speech of Dick Martin, the drummer."

"I don't know how to do it, captain; and yet he's one of us."

"Exactly. I will show you how to do it, Atkins. I am a prisoner here; I suddenly become ill and faint; I require a draught of water. Then you see I sink upon this chair; I rest my head upon my hand (nothing is more natural); you go to the door and call out that the prisoner is ill, and summon Dick Martin to bring some water."

"I see, captain. I'm no scholard, but I see that. Bless you! sir, you've given me a piece of gold along with the crown-pieces."

"Never mind, keep it."

"Long life to your honour!"

"Atkins! Atkins! Is it possible that you do not see that I am ill and require a draught of water?"

"Certainly, your honour, certainly. Hullo there! Guard! guard! The prisoner is taken ill!"

"What now?" asked the sergeant, from the further end of the passage immediately without, the cell.

"Prisoner ill, sergeant—wants some water. Perhaps Dick Martin had better bring him some."

"Hold your post, sentinel. I'll see to that."

There was soon a rapid footstep in the passage, and the young drummer boy appeared, with a tin can, some three parts full of water.

"Atkins," said Captain Markham, "you will parade your post, and, hearing nothing, seeing nothing, can be blamed for nothing."

The boy had a look of commiseration upon his face as he held the tin can close to the lips of Captain Markham. And so they looked at each other across the margin of that common barrack-room tankard, by the dim light of the swinging inodorous lamp.

"Dick," whispered Markham, "I think I have been kind to you."

"Yes, sir, and—"

"Hush! hush! Hear me out, for I know not what time I have to speak to you. Have you a father and mother, Dick?"

"Lor, yes, sir. Ever so far, Gloucester way."

"Are they poor?"

"As Job, your honour. I believe he were poor."

"Then, Dick, take this. It is a jewel, which will make them rich. You will manage to give it them, and I dare say they will find some means of disposing of it. Hide it, Dick, hide it about you. And now listen to me. I wish you to do a service—not to me, but to another. And when you are a grown man, Dick, and a brave soldier, as without doubt you will be, the thought of what you do this night —for I am sure you will do it—will be to you a delight and a joy for ever."

"I'll do it, captain."

"Go to old Whitehall—go at once—make your way into the building—back, front, any way. And when you get there rail out aloud, 'Bertha! Bertha! Bertha!' Keep calling that name aloud until a young girl replies to you—a young girl about your own age, Dick. And when you see her tell her from me—and tell her, too, that I sent to her by the memory of her dead father—tell her from me that she is to fly—fly instantly, to leave that place, leave London, leave England—that she is to fly for her dear life's sake. Go, Dick, go now, and may Heaven protect you, for your errand is one of mercy, and must be blessed. Go, go at once."

The soldier at this suddenly paused in his monotonous march to and fro.

"Hush! captain. The guard!"

"Ah!" Tramp, tramp, tramp came the regular military march of armed men towards the door of the cell.

"Remember, Dick. Oh! remember."

"Sit down, captain, you're worser."

Captain Markham rested his head upon his hand again, and Dick Martin, with a look of great interest and commiseration, was splashing some water on his face as the door was flung open, and a sergeant's guard appeared, the foremost man of which was carrying a lantern, which shed a bright flickering light over the accoutrements of the soldiers, and likewise shone full upon the little group in Markham's temporary prison.

CHAPTER XXXII.

CONDEMNATION.

The sergeant looked into the cell with commiseration.

"I am better," said Captain Markham, as he rose.

The sergeant spoke in a tone which evidently betrayed some emotion.

"Orders," he said, "for prisoner to fall in and march to guard-chamber."

"I am ready. Oh! Dick, when shall I know that you have gone?"

"A tap on my drum, captain."

"Right about face! March!"

Two minutes conducted Captain Markham and his guard along a passage and up a short flight of six steps to one of the doors of the officers' guard-chamber.

"Halt!"

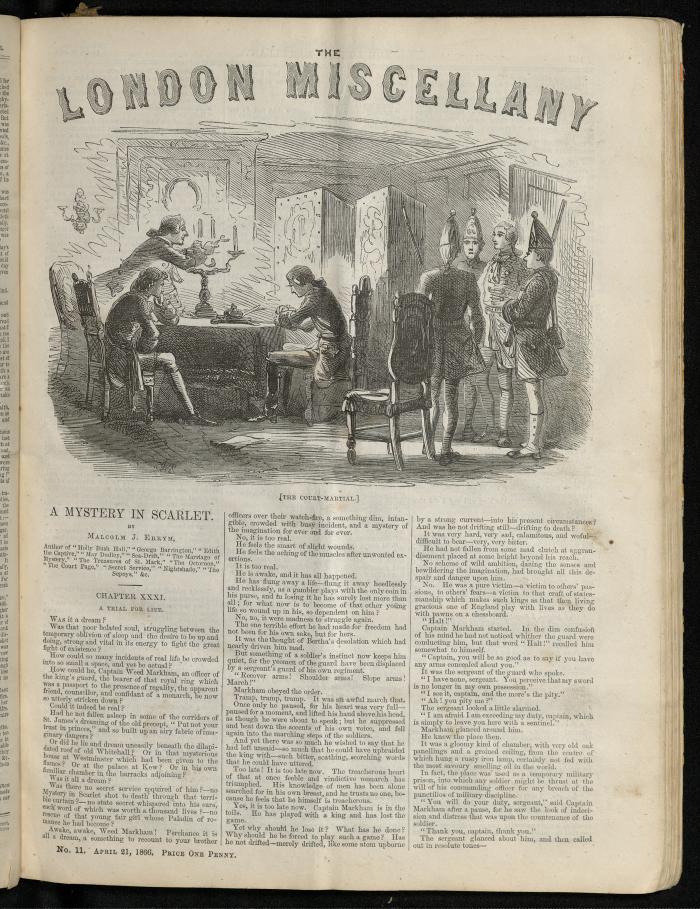

The sergeant struck at the door with his halbert. It was immediately opened from within by a sentinel, and the sight which presented itself to Captain Markham was curious in the extreme.

There were three persons in that apartment, and that they were officers in the full uniform of their rank he could see at a glance.

A rather large silver candelabrum, carrying four wax lights, stood on the centre of a long table in the middle of the guard-chamber, and at the moment Captain Markham looked into that place one of the officers, who was in the uniform of a general, seemed to be desirous of extinguishing all the lights.

He did extinguish three of them.

The four that he still left alight shed but a dreary twilight around it.

"Captain Weed Markham," said the general officer, "will advance."

Markham stepped into the room.

"Halt, sir."

Then Markham knew who it was that addressed him, for from the voice he never would have acquired that information, so strangely altered and unnatural was it.

It was General Bellair who spoke, and who had extinguished the candles.

No possible art, theatrical or scientific, could possibly have succeeded in so completely destroying the identity of any individual to the extent that shame and agony altered that of General Bellair.

Pale, haggard, and shrunken, he looked the wretch he felt, shaking, trembling, and shuddering, on the threshold of a crime that his shrinking soul seemed to whisper to him must close for ever against him the gates of that mercy which yet is so infinite.

But the man was in a kind of trance.

Selfishness, ambition, the dread of poverty, the despair of such a fall from which nothing could again raise him, the brilliant offers of the king, wealth, nobility, court fayour—and what was the price after all? Only a life! only a life! Why, men take lives in the battle-field and think it honour. But this was not a battle-field. Oh! no, no. That were glory—this murder. Subtle distinctions, perhaps, but they held on to the heart of General Bellair like vulture's talons.

But there are two other officers present. One, who has uttered an exclamation, accompanied by a start, at the sound of Markham's name.

Another, who rests his head upon his hand, and seems to dread to look up.

"Gentlemen," said General Bellair, and he spoke in so strange and hollow a tone that it seemed to come from afar off, and to belong to no human lips there present. "Gentlemen, this is a summary court-martial, held to try an officer for one of the most serious military offences it is possible for him to commit. Gentlemen, you will take your seats, and, as the federal in command of the troops now doing duty in the London district, I preside at this court-martial, and declare it duly constituted according to the Articles of War."

"General Bellair, I protest!" exclaimed Markham.

"Protest? You protest, sir?" half shrieked Bellair.

"Protest me no protests, sir! We sit here commissioned—"

"By whom?"

"The king. Yes, gentlemen—yes, officers and gentlemen—commissioned by the most gracious of monarchs, his Majesty King George the Second of these realms, our serene and gracious master."

Norris had stepped into the guard-chamber, and, duly proportioning his bows to his estimate of the value of the company in which he found himself, he only bent at a very slight angle to General Bellair.

"I have the honour," he added, "the singular honour, which will always be a delight for the remainder of my unworthy existence— the singular honour to be—"

Norris stopped short in his speech, and stepping up to General Bellair, he placed before him a half-sheet of writing paper, and upon it the general read the conclusion of Norris's speech—

"Empowered by the king. Given at St. James's.

"GEORGE REX."

Norris rubbed his hands slowly one over the other, and looked into the face of General Bellair.

Then the young Marquis of Charlton, who sat between Lieutenant Ogilvie and the general, spoke in earnest tones.

"I do not pretend, General Sir Thomas Bellair, to be either so old a soldier or so experienced a one аs yourself, but I never heard—I never read of such hasty proceedings as these. Surely they are most exceptional."

"Yes, colonel," replied General Bellair, "they are exceptional, and so is the offence; but Heaven—that is to say—I—I —I mean justice forbid—that is, I hope we are not hasty. But it is competent on the part of officers on actual duty to sit, as we are sitting, in court-martial, provided the occasion seems warranted by the highest authority, and I believe no one here will dispute that his Majesty is the head of the army."

"I must bow to the authority," replied the Marquis of Charlton, "but I hope we shall find something in the circumstances themselves which shall warrant us in taking such a view of the matter that if there be haste or irregularity they will not be of material moment."

"We all hope so," said the general.

"But, general," interposed Lieutenant Ogilvie, "is it not an exceedingly dangerous thing that any officer, not in a time of war, should be summoned thus to what I may call a drum-head court-martial. These things are done in the field, and in the heat of a campaign, but here, in the palace of St. James, not a hundred paces from his Majesty's private apartments, it really seems to me that—that—"

"My dear sir," whispered Norris, "my dear young

p. 163

man, his most gracious and serene Majesty wants to sleep in peace and to forgive all his enemies, this prisoner included. Do you comprehend me? Of course you do. Let him be irregularly convicted. Can he not then be regularly pardoned, and all in an hour? My dear young man, consider. Are you acting аs the friend or the foe of Captain Weed Markham? Bless him!"

"I hear what you say, Mr. Norris, and it may be sо. Of course I must act as my superior officers dictate, and in the meantime pray keep your distance from me."

"Distance?"

"Yes."

"If you do not I will fling you through that window as soon аs look at you."

Norris placed a respectful distance between himself and the young officer in a moment.

"Hem! hem!" he murmured. "A violent young man. Something will happen to him one day, I shouldn't wonder."

"Gentlemen," cried General Bellair, "since we are now regularly sitting, we—"

"Still I protest," interrupted Captain Markham. "This is a farce. No officer or soldier, be he the meanest and lowest in the service, can be brought to a court-martial in this fashion. I demand four-and-twenty hours, in which to prepare my defence."

"The prisoner protests," said General Bellair, as he wrote rapidly on some paper before him—"the

prisoner protests, and demands four-and-twenty hours in which to prepare his defence.

Both points reserved for the consideration of the court. I now call upon his Majesty's representative to state the charge against the prisoner. First of all, however, I ask him to declare himself by name and title."

"I declare nothing," said Markham, "since I protest against the legality of this whole proceeding."

"Now, Mr. Norris."

Norris crept forward. "I have it in command from his most gracious Majesty to state that the prisoner now before this honourable court petitioned his gracious Majesty for an interview, and his Majesty, with that noble condescension which renders him accessible to the meanest of his subjects, even me, granted the interview."

"It is false!" said Markham.

"Silence, prisoner; your time will come," said the general.

"At that interview," continued Norris, "the prisoner demanded of his Majesty, under the pretence of being in possession of some state secret, repugnant to the feelings of—"

General Bellair waved his hand.

"Enough, enough, Mr. Norrie. The feelings of his Majesty are of too sacred a nature to be made the subject of discussion here."

"It was not his Majesty's feelings," interposed Norris.

"It was the fatherly regard and the tenderness of heart with which his gracious Majesty looks upon all matters connected with his beloved son Frederick."

Markham listened with wonder.

"It is very probable," added Norris, slowly rubbing one hand over the other, "it is very probable that, out of rage and spite and disappointment, the prisoner may tell some quite different story now, but it was about that blessed Prince Frederick, the hope of the nation. I need not say what it was, but when his most gracious Majesty refused to purchase the pretended guilty secret the prisoner drew his sword and threatened the life of the king."

General Bellair held up his hands.

"Treason! gentlemen, treason!"

"I deny it," exclaimed Markham. "His Majesty demanded my sword, and I tendered it to him by the hilt, and even if the facts were as this dastardly lying cur has stated, they are not matter for a court-martial."

"They are, sir," exclaimed Bellair. "If his Majesty chooses to sink the monarch to his undoubted rank as commander-in-chief of the forces. You are not arraigned for assailing the king, but for drawing your sword upon your superior officer."

"Which I did not."

"That is the question."

"Yes," cried the Marquis of Charlton, "and a question still. General Bellair, can we, as officers and gentlemen, sit here and accept the evidence of a man like this against any other officer and gentleman."

"It is scarcely consistent," said General Bellair, turning whiter as he spoke, "it is scarcely consistent with his Majesty's dignity to appear before us as a witness."

"Hem!" said Norris, as he glided forward and placed another paper before the general. "Hem! I am prepared to state that—"

Norris paused as he had done before, and General Bellair finished what he was saying by reading the paper.

"The prisoner drew upon us and presented his sword traitorously at our breast. Given at St. James's.

"GEORGE REX."

"And now, gentlemen," added General Bellair, "what say you?"

There was an awful stillness.

"Captain Weed Markham," then said the Marquis of Charlton, "on your honour as an officer and a gentleman, did you do this thing?"

"I did not, colonel."

"Ha! ha!" yelled Norris. "He gives the lie to his king—to the best of kings—the most gracious—and by implication, by implication, gentlemen, he calls him the most selfish and murderous old scoundrel that ever existed, whom nobody will serve but for what they can get by fair means or foul in a few short years, and then leave him to rave and rot! Ha! ha! To rave and rot! By implication, gentlemen, implication! Ha! ha! Bless us all! By implication—implication!"

"Silence!" cried General Bellair. "Lieutenant Ogilvie, you have heard the charge against the prisoner. What say you? Is he, to your judgment, guilty or not guilty?"

"I dare not—I dare not," cried the young man, "say the king lies, and so, as the king speaks the truth, then is the prisoner guilty."

"Colonel Marquis of Charlton, what say you, having heard this evidence? To your judgment, is the prisoner guilty or not guilty?"

"Not guilty," said the marquis boldly.

"Not guilty, colonel?"

"No, not guilty. I have an opinion that his Majesty is mistaken, and that as the prisoner never intended this grievous offence, he cannot be called upon to answer for it."

"But, colonel—"

"Nay, general, it may be a very natural mistake. The prisoner, in the heat of some argument or illustration, may have drawn his sword, but yet with no evil intentions, and in illustration of my opinion I wish to ask the witness Norris (for we must look upon him as a witness) one or two questions."

"Oh! certainly—hem!—certainly. Bless us all! Oh! certainly."

"Where did the prisoner see the king?"

"In his private cabinet."

"How did he get there?"

"He was conducted by Mr. Page of the Back Stairs."

"Were they alone? I mean his Majesty and the prisoner."

"Yes, alone."

"And what became of the sword said to be drawn upon the person of the king?"

"His gracious Majesty had it, and handed it to me. It is here."

"Then I am quite sure his Majesty, upon reflection, will see that a young athletic man, accustomed to the use of weapons, like the prisoner before us, could have had no difficulty in taking his life, had he been so inclined; and it is yet to be explained, except upon the statement of the prisoner himself, now his Majesty, who is certainly not the stronger of the two, succeeded in wresting a drawn sword from a man accustomed to use it, who is twice his size and ten times his strength."

"Oh, dear!" said Norris. "Oh, dear! This is revolutionary. How should we say what strength is given to the anointed ones of the earth? Oh, dear! I am afraid, marquis, I ought not to report what you have said to his gracious Majesty."

"That you may please yourself about; but I say, Not guilty."

"Then," said General Bellair, "the prisoner is convicted by a majority of the court."

"No! no!" cried Lieutenant Ogilvie.

"Sir, you have already given your opinion. The prisoner is found guilty, and the sentence is—"

General Bellair let the words stick in his throat, like Macbeth's " Amen," and something little short of a convulsion shook his frame before he could utter the word that was upon his lips—

"Death!"

"Death!" echoed Norris.

Lieutenant Ogilvie was shocked and terrified.

"We will recommend him," he cried, "to the mercy of the king."

"Assuredly," replied General Bellair.

"Assuredly," echoed Norris. "Ha! ha! ha! he! hem!"

CHAPTER XXXIII.

WAITING AND HOPING.

And now should he tell all?

That was the question Captain Markham asked himself.

In this fearful extremity of his fortunes, would it be wise, would it be right for him to make what is commonly called "a clear breast" of the state secret that oppressed him?

For a few moments the natural feeling was at once to state clearly and distinctly why he had incurred the bitter and jealous hatred of the king, and why it was his death was considered necessary to the royal peace of mind.

It was but for a few moments, however, that this mode of action seemed to present itself in anything like attractive colours to his mind.

Almost along with the suggestion he felt that it was neither wise nor just. Not wise, because by making such a revolution he would in all probability only brand his memory with some feelings akin to disgrace in the eyes of those persons who were before him, and who, however harshly they might scorn to be judging him, might believe that they were doing their duty.

Moreover, what right had he to burden that young Marquis of Charlton and the subaltern Lieutenant Ogilvie with a secret that might cost them both their lives?

And, moreover, and above all, the revelation could not well be made without mentioning Bertha, and so perhaps hindering her escape from the position of extreme peril in which she stood.

And yet the disposition to speak for the few seconds during which the idea of doing so was uppermost in his mind was so apparent that he received two interruptions.

One was from Lieutenant Ogilvie.

The young subaltern had a faint faith yet in what had been asserted by Norris—viz., that the king intended to pardon the prisoner so soon as he was justified in doing so by having him at his mercy.

The other interruption was from the Marquis of Charlton.

"Not a word," he said, as he held up his hand. "Wait and hope."

General Bellair was busy writing.

In due form he made out the finding of the court-martial.

Then, by a look bespeaking the attention of his colleagues and of the prisoner, he read in slow low tones—so low, indeed, that they could scarcely be heard even in the perfect stillness of that apartment—

"At a court-martial assembled in the guard-room of St. James's Palace, for the trial of Captain Weed Markham, on the charge of drawing his sword on his superior officer, the members of such court-martial being Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Bellair, General Commanding the London District, Colonel the Marquis of Charlton, of his Majesty's Light Horse, and Lieutenant Bernard Ogilvie of the Coldstream Guards, upon sufficient testimony the prisoner was found guilty and sentenced to death, such death being in the form of a military execution."

The general looked up.

"I have signed this record," he said, "as president of the court-martial."

"But the recommendation to his Majesty's mercy?" said Ogilvie. "I do not hear that."

"It shall be appended."

The general wrote again, and then read in a louder tone—"the prisoner is further recommended to his Majesty's mercy."

There was a look of scorn and indignation on the face of Captain Markham. His heart was full, nearly to bursting, with the sense of the gross injustice of his treatment.

He recommended to the mercy of the man whose life he had saved only so short a time before!

Who had there been to recommend to his mercy that most ungrateful king when he stood in such dire peril and alone in the disused chambers of Whitehall, and with at least a dozen swords ready to shed his heart's blood?

The young Marquis of Charlton saw the flush upon the cheek of Markham, and, holding up his hand, again he said once more—

"Wait and hope."

"It is impossible—quite impossible," whispered Lieutenant Ogilvie, as if he liked to hear the sound of his own voice uttering the assurance—"it is quite impossible his death can be intended. That rascal Norris will bring back the pardon of the king."

General Bellair handed the written paper to the valet.

But Norris did not take it.

"Perhaps, general," he said, "you would like to present to his Majesty yourself the finding of the court?"

"No. I am on duty here," replied General Bellair gloomily. "Take it."

Norris was absent about ten minutes.

During that time General Bellair strove to put on a look of friendly familiarity to the Marquis of Charlton.

"We shall see you in Spring Gardens to-morrow, my lord, doubtless?"

"I think not, general."

"Agnes bestows her company upon me once a week, and I thought, marquis, that you would be but too well pleased to pass an hour or two with us in our humble home."

"I think not, general."

"You speak in riddles, marquis. I do not understand you.

"It is not in accordance, General Bellair, with my honour or with yours, nor with the feelings of gentlemen, that I should be more explicit."

"But, marquis, this conduct, after our compact—our agreement."

"There is no compact, general—no agreement. I have but to wish the Lady Agnes Bellair every happiness that this world can afford her, and at the same time, feeling my own unworthiness, to withdraw all pretensions to her hand and heart."

"Marquis!"

"General!"

p. 164

Bellair looked malignantly into the eyes of the young officer.

"There is more in this," he murmured, "than I understand. But it matters not. The Lady Agnes Bellair, my daughter, stands upon too high a pinnacle of—of—"

"General! General!" interrupted the marquis, "understand me, once and for all—for as this is the first so it shall be the last time on which I shall speak to you on this subject—understand me, then, clearly. There is no imputation upon the Lady Agnes Bellair, and you may call it caprice or what you will, but I withdraw my pretensions to her hand."

The general bit his lips.

It had been something in addition to his own personal barony to have his daughter a marchioness.

His only consolation was that he might still quarrel with his son, a reconciliation with whom had been one of the conditions of Agnes's consent to an union with the marquis.

Further consideration, however, of that subject was put an end to by the reappearance of Norris, who, in a crouching attitude, placed before the general the same document he had taken away with him.

Then Sir Thomas Bellair read in a low tone the following words: —

"Finding and sentence confirmed. Execution immediate.

"GEORGE REX."

Both the Marquis of Charlton and Lieutenant Ogilvie sprang to their feet.

A faint smile crossed the features of Captain Markham. It was like the white gleam of sunshine on a wintery day.

"I knew it," he said quietly. "I knew it."

"But the recommendation to mercy?" exclaimed Ogilvie.

General Bellair shook his head.

"We can only recommend. It must be left to his Majesty to decide. Sentinel, you will summon the guard. Captain Weed Markham, you will be kept in close custody for twenty minutes, during which time I recommend you to make your peace with Heaven."

"Hush! General Bellair," said the Marquis of Charlton. "Let us have no profanity, if you please. All that Heaven will have to do with this business will be to seek from its font of mercy some small consideration possibly for those who have taken part in these proceedings. I will not characterise them by the word that was upon my lips, for the air of St. James's is not wholesome to those who deal in candid expressions, and I certainly hold the king's commission."

"I thank you, colonel," cried General Bellair, with intense bitterness of tone and manner. "I thank you for reminding me of that, because it enables me, as your superior officer, to order you to see this execution carried out. On your own head be it, Colonel Marquis of Charlton."

"I accept the office, and be assured, General Bellair, that I will not belie my name or my ancestry, for I know my duty, and will do it."

Grasping his sword and scabbard by the middle, the Marquis of Charlton strode from the guard-chamber. the young subaltern looked bewildered, and stood like a man entranced, watching what was going on.

The door was flung open, and the sergeant's guard, which was to convey Captain Markham to his cell again, stood under arms in the passage beyond.

There was too much defiant pride in the breast of Markham to permit him to say a single word to General Bellair.

But they looked at each other fiercely, those two men, neither of whom had ever before come into contact with each other antagonistically.

But now their gaze was as that from the murderer to his victim-—from the victim to his destroyer.

The general strove to maintain the gaze unflinchingly, but he could not do so, and slowly he withdrew his eyes, becoming whiter and whiter as he did so, for the striking phenomenon then and there present in the mind of General Bellair was that he was perfectly conscious of the abundant wickedness of his own actions, while yet he blundered on like a man in the hands of some resistless fate which he could not resist.

"Right about face! March!"

Two minutes more, and Markham was alone.

Quite alone now.

There was no sentinel pacing within the narrow confines of his cell.

Was it wished to give him the chance, now that his ultimate fate seemed certain, for laying violent hands upon himself, and so appearing to justify his condemnation?

It might be so.

No such thought, however, found a home in the breast of Captain Markham.

On the contrary, he was rather surprised at his own calmness.

It was a strange kind of calmness, however—a kind of still dull apathy—the apathy of a man who feels himself scarcely, still yet belonging to the world which is so soon to fade away from him.

The loneliness of his life and the mystery of his birth had invested that young officer's mind with a certain atmosphere of sadness not fayourable to a brilliant or ecstatic view of life.

But still to be murdered—murdered in cold blood!

And all for what? For becoming the accidental possessor of a secret he had not the remotest idea of using for a malignant purpose. That was hard—very hard.

But he was to die a soldier's death—such a death as might have overtaken him on the battle-field at any moment, for wars and rumours of wars were in the public mind, and a smouldering campaign was going on in Germany, where he might have been ordered at any time.

But still it was hard, and began at moments to grow into an anguish, to be shot down by his own comrades—to die perchance an easier death than on a well-fought field; but how different an one!

The applause, the glory, the din, the rattle, and the excitement of war—those were the things that shed the halo of their own lustre about, the grave of the dying soldier.

But this death, this execution—so different—so very different!

"Calm! calm!" he said to himself. "Oh! be calm. It is but a moment—one awful plunge from life to eternity. And who is there will mourn me? Who regret me? Where are the tears that will flow for my memory? Yes, there is one whom I could have loved, and the fire of that passion still smoulders—smoulders here—here in the depths of my inmost heart. Agnes Bellair, I never knew how much I loved you until this moment. And how strange it is, in the history of the mysteries of the human heart, that there should be even such a moment as this—a moment when, with all my soul and all my strength, I thank Heaven, Agnes Bellair, that you do not love me, and that you have probably forgotten the very existence of the young soldier whose life and whose death will be the gossip of a few days only at this crime-steeped court of old St. James's. And Bertha too! Poor girl! Heaven help her now! And if I have a special prayer for her beyond that which I utter for her escape, and that good angels may guard her to a place of safety, it is that she may never know the real secret of the Mystery in Scarlet."

The palace clock struck.

It was eight.

There is again a rattle of arms in the gloomy passage without the cell.

Captain Markham had flung himself into the only chair in his prison.

But at these sounds he sprang to his feet.

A sudden paleness, then a flush, then a paleness again, and the set features were calm and rigid.

"Farewell!" he said. "In five minutes more the great world's secret will be mine. Farewell!"

* * * * * *

The rain still fell gently and with a soft patter on the stone flags of the Colour Court.

There it accumulated in pools, in which were reflected the low faint lights from the palace windows.

There was an unusual warmth in the air, for the soft gentle south wind that had brought with it that summer-like rain had travelled far over the burning wastes of a huge mysterious continent, and not even the strip of ocean it had traversed had been sufficient to cool its fervid heat.

And there in the doorway still crouched Bertha.

There were various little incidents which had broken the tedium of her watch.

She had wondered what mysterious communication the sentinel who was relieved had to make to him who came on duty.

Twice or thrice some official of the court, in what to her had appeared a strange old-world costume, had flitted past.

She somewhat wondered, too, what a drummer boy could mean by standing out in the middle of the court in the rain, and giving one light sharp tap to his drum.

But he did so, and then a sergeant of the guard came hastily from under an archway and spoke angrily, and he and the drummer retired wrangling together.

These little incidents broke the monotony of her long watch for Captain Markham, and still every now and then she held out her hands to catch the passing shower, and was as pleased as a child at the freshness, the warmth, and soft gentleness of that evening hour.

Poor Bertha!

(To be continued in our next.)