A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER IV.

A PICTURE OF THE PAST.

"Hear the Ferret! Hear him! Hear him! Hurrah for the Ferret! Look at his eyes! Hear him! Hear him! Bring him up! Forward with the Ferret! Drop the blanket there! Now, my merry men all, we'll hear the Ferret! On to the table with him! You, big Peter, stand by the blanket, and let no one in without the sign three times repeated. Hurrah! Hurrah! A cheer for the Ferret."

In a dim underground apartment (or cave, as it might be more properly termed) some forty persons were assembled within a quarter of an hour of midnight on that same night when Captain Weed Markham was passing through that fatal episode in his existence at Kew, which was to change the whole current of his life.

The locality is Westminster.

The place a large underground straggling cellar, or series of cellars, beneath the old celebrated, but long since forgotten, hostel of the Red Cap.

The atmosphere is heavy with the fumes of tobacco.

Some chance, probably a plunder from the river, has littered the coarse wooden benches with those odd misshapen bottles, black, opaque, and tottering, which are popularly supposed to contain that celebrated Schiedam with which the Hollanders fortify themselves against the damps and fogs of their dykes and lagunes.

The only apparent entrance to the cellar has a large thick blanket hanging over it, which, originally heavy and massive in its manufacture, seems to have acquired additional weight and solidity from dust, mud, and grime of all sorts upon its surface.

The company at first sight would seem a mixed one.

But that would be only to judge them by their costume.

One would fancy, to see some of them, that they were representatives of the soberest and demurest of the tradesman class.

Others, again, had the rakish raffish look of broken-down men of fashion.

A few were attired in mendicant's weeds, but those who presented externally such an appearance wore even their rags and tatters with an air as much as to say, "We put on this special appearance for a purpose, and for a disguise which it is not necessary for us here to maintain."

The president of the evening (for even these outlaws of society felt some sort of government necessary) was seated on a chair elevated on the end of the long rough tables, and he presented all the external appearance of one of those rakish bullies of which the town was then so full, and who were in many cases the remnant, so to speak, of the Scotch civil wars then so frequent.

"Silence, gentleman all. Silence I say, and let us hear the Ferret."

"Oh, the Ferret will keep, noble captain. Let us have some of the Dutchman's strong waters."

"Big Peter."

"Your sarvint, noble captain."

"Knock him down."

"There he goes, noble captain."

"Now, my fine fellow and roystering companion, you'll contradict my orders another time, will you? And now for the Ferret."

A thin wily individual, with the most cat-like human eyes it is possible to conceive, advanced slowly towards the end of the table occupied by the president.

A quiet shabby suit of the tint then called snuff colour and a cravat that might at some distant period have been white made up, with what is called a scratch wig and a battered three-cornered hat, the costume of the Ferret.

Lifting his hat a few inches above his head, with an affectation of grace and politeness, the Ferret placed his disengaged hand upon the region of his heart and executed a half bow.

"Hear him! Hear him!" shouted a dozen voices. "Hear the Ferret. There never was a better one, and never will be."

"Silence!" shouted the president.

Then, to the intense gratification of all there assembled, he tapped out the ashes of his pipe on the head of the Ferret.

"Drink, Ferret, drink. The old Schiedam will clear your wits."

The Ferret bowed again, but the joke seemed to be that although half a dozen glasses, mugs, pannikins, and bottles were held to his lips, he was not allowed to drink from any.

But the Ferret was unmoved by these slights and insults.

There was the same sad smile upon his face.

He executed whenever occasion served the same half bow.

"Order now! Order!" cried the president. "And you, big Peter, knock any man down who says a word. Listen, merry men all. Don't you hear the old Abbey growling out twelve o'clock? and here we are mooning the night away, and nothing on the lay. Silence I say, and hear the Ferret. What do we keep a Ferret for, and give him share and share along with us all, whether it come from the road, the street, or the roost, if we are not to hear him? Now, Ferret, say your say. What's on the cards to-night? and how are our merry men to fill empty pockets?"

The Ferret coughed slightly.

"Gentlemen all, this being Thursday night, it is my humble duty to attend upon you and report if I have ferreted since our last meeting any safe and profitable lay."

"Hear him! Hear him!"

"Silence, I say again."

"I supposes as how we may drink, captain?"

"You may; but take care it's enough, and then we shall get rid of your noise for the rest of the night. Now, Ferret."

"Noble captain and gentlemen all, I've been here and there and everywhere, on the highway and the byway, the streets, the mall, and in the roost; but since that little affair with the Duchess of Northumberland at Charing Cross, and that other one with my Lord Hervey on the Western Road, the nabs have been active,

p. 18

and I wouldn't advise any good friend of mine to look for sport in that way just now. But—"

"Well, Ferret—but?"

"There's a roosting game, which, good friends all, you know means that there is something to be done within four walls while somebody else sleeps."

The Ferret spoke in so mysterious and low a tone that every head was inclined towards him to catch what he said.

The noble captain, as the gentleman in the chair was styled, even put down his pipe and listened.

"Well, Ferret, what is it?"

"It's something I've been at for weeks and weeks, but if it's half, or a quarter, or half a quarter, or half or a tenth of that again what it seems to be, you are all made men."

"No!"

"Yes, noble captain and gentlemen all."

"Out with it, Ferret. Out with it."

"Drink, Ferret, drink."

"No, no. This is no time to drink, and it's so strange a story, noble captain and gentlemen all, that I for one should like to know and feel sure—"

"Sure of what, Ferret?"

"Why, that we're all good men and true here."

"Ah, yes."

A glass was accidentally broken at one of the tables.

"Silence!" cried the captain. "You big Peter, keep the blanket. Our Ferret is an old hound, and don't give tongue till he sees the game."

"Bravo! bravo! Hear him! Hear him!"

The captain waved his hand authoritatively for silence.

"I don' t mean to say for a moment, gentlemen," added the Ferret, "nor is it at all likely any one is here present that don't belong to the honourable family, but this little affair, noble captain and gentlemen, is a matter of life and—and—"

"And what, Ferret?"

"Death!"

The Ferret's eyes seemed to look two ways at once as he uttered this word, and his thin lips curled inward more than before.

"Let every man," said the captain, speaking with deliberation, "let every man here present walk past me, between the back of my chair and the wall. There's just room enough. And as he does so he can whisper to me the word which makes us good fellows all and hail, well met."

"Bravo! bravo! Hear the noble captain. That's the way."

The whole party tumultuously rose, with the exception of one man.

A tall muscular-looking individual in a faded scarlet coat with heavy lappels, and a cravat the loose ends of which were ostentatiously tucked in at one portion of his waistcoat and projected from the other, suddenly thrust back the rough stool on which he sat until he reached the wall, and then, in a calm steady voice, he spoke—

"Gentlemen all, I know no words, for this is no crib of mine. I hunt the highway, the common, and the heath, and my horse is at the Chequers. I know no words, I say, but if blows will do as well, I'm ready for any couple of you at a moment's notice."

A roar of execration burst from the assembled thieves, and it was with difficulty the captain commanded silence.

Some threatening gestures were made at the stranger, and one or two knives gleamed from secret receptacles.

"Ware hawk, if you please, gentlemen," added the stranger. "Wherever I go there are generally three of us. I'm one, and these two little pop-guns are the other two."

As he spoke the stranger presented a couple of pistols in an easy nonchalant manner, but in such a direction that were he to discharge them they would inevitably take effect upon the president and the Ferret.

The latter shrank back, and the president in an absurd way held out his pipe, as if with the bowl of it he could intercept the shot.

"Tush, man! tush!" he cried. "Put up those pops, and just say how you саmе here."

"With all my heart. Ned Forrester, the mighty good host of the Red Cap, showed me the other side of yonder blanket, and I suppose vouched for me to your ugly giant there, Peter, as you call him."

The thieves looked in each other's faces irresolutely.

"Give him the oath," said the Ferret. "Make him one."

"Yes, yes. That's it. Make him one. Make him one."

"Fair and softly," said the stranger. "I strolled in here for a drink, a song, and a carouse, nothing more, and I am willing to go as I came, knowing nothing and therefore not in ease to betray anything."

"No, no!" cried a dozen voices.

The stranger rose and stepped towards the blanket.

"And why no?" he shouted. "Are you so fond, all of you, of being laid fast, and told you shan't go here or there, that you wish to make a caged bird of me? Now, Peter, I'll thank you to remove that bullock's hide of yours out of the way."

"Not if I know it," growled Peter. "Who are you, I should like to know, that—"

Peter terminated his growling speech with a yell that rang through the cellar, and with one tremendous leap he sprang into the midst of the thieves, who had hastily risen from the stools and benches.

"Good night," said the stranger.

The blanket was rapidly moved on one side and in another instant he was gone.

A dozen voices demanded of Peter what was the matter, but to the best of his belief he didn't know, except that a flame, a flash of lightning, or something red hot had begun to make its way in at his back as he stood on guard by the blanket.

And sure enough there was a small charred orifice in Peter's coat just between his shoulders, and a corresponding still smouldering minute aperture in the blanket.

But the stranger was gone.

"What does it matter, gentlemen all?" cried the captain. "He's off, be he whom he may, and he knows nothing."

"He looked a high-flyer," said the Ferret. "And as this is a roosting lay, we certainly don't want him."

"Drink, Ferret, drink."

"Water. I feel parched."

The captain shook his head.

"You won't get that here, Ferret; but are you content now that all here present are good and true family men?"

"I am now, and so, noble captain and gentlemen all, I want to ask you a question."

"Out with it, Ferret, and speak up."

"So, with all deference to you, this is not a matter to speak up about."

"Go on, then. Go on."

There came a faint flush of colour into the face of the Ferret, and his eyes seemed to describe concentric circles in their orbits.

"Do you, noble captain, or do any of you, or do all of you together think you can muster up a fair notion of what half a million of money means?"

"Half a million!"

"Half—a—million?"

"I have said it."

The captain placed his hand upon his brow.

"It's five hundred thousand all in gold. It's millions in smaller coin. It's—it's— You don't mean half million, Ferret?"

"I do."

The thieves drew long breaths and crowded in a strange motley throng about the upper end of the cellar. Even big Peter forsook his post at the blanket and approached to glare, in the eccentric eyes of the Ferret.

"Half a million?" repeated the latter. "And — and—"

"Hush! hush!"

Every man hushed down his neighbour.

The Ferret licked his lips, and nothing but the whites (if whites they could be called) of his eyes were visible.

"And only two lives in the way."

"Two lives?" murmured the thieves.

"Ferret," said the captain. "Aye."

"Must those two lives go?"

The Ferret nodded.

The thieves looked in each other's faces, and then the captain, as he gazed up at the begrimed ceiling of the cellar, muttered to himself, "Half a million. Half of ten hundred thousand. Ferret, you are mad."

CHAPTER V.

MURDER IN THE AIR.

The Ferret's eyes assumed another phase, which seemed to represent the small pupils in totally opposite corners.

"I am not mad, noble captain."

"Then speak out."

"I will. You know these are the cellars of the old Red Cap, where they say more crimes and conspiracies have been hatched for these last hundred years than in any other house in London."

"What of that, Ferret?"

"Not much. But next door some of you may know is the house where Sir Thomas Mears was murdered by the wild and profligate уoung Lord Overton. They called it a duel, and they do say that Lady Mears held up a couple of candles while they fought, and, when Sir Thomas was killed, drove off with the young lord, and sо the house was deserted until lately, when it has had two inhabitants."

"Well, Ferret?"

"A man with something of the look and carriage of a soldier. He usually wears a faded roquelaire cloak, and underneath, as I have accidentally seen it blown aside by the wind or carelessly worn, a scarlet coat."

"Well, Ferret?"

"The other person is a young girl."

"A young girl?"

"Yes. I should take her to be some fourteen or fifteen years of age. She is fair and—and—innocent and—and—"

"Well, Ferret?"

The Ferret drew a long breath.

"Half a million."

"But what do you mean by it? What do you mean by your half million, and your odd looks, and your man in scarlet with the roquelaire cloak, and your young girl? How does it all hang together, Ferret?"

"I will tell you. I am a Ferret, as you call me— the Ferret of this honourable company—that is to say, I insinuate myself into strange places—I listen—I lie in wait for information—I pry into secrets and ascertain the depositories of gold and valuables—I discover how they are guarded and by whom."

"Good," said the captain. "And many a rich lay you have put us on."

"But this," added the Ferret, "transcends them all."

He lowered his voice still more, as he spoke, until it had decreased almost to a whisper.

"Watching this man and the girl, and wondering who and what they were, I bethought me of getting out on the roof of the old Red Cap, and so seeing if I could make my way into the next house. It was not difficult, and light as a cat I dropped into one of the attics. Creeping then down the staircase, I heard voices, and in the large room at the back on the first floor I found that the man was speaking to the girl in such earnest tones of excitement that, crouching on the staircase, I heard all he said."

"Well, Ferret, and what was it?"

The Ferret licked his parched lips again, and then, half closing his eyes, as though by that process he could look with the other half back into his memory for the exact words he wished to repeat, he spoke slowly.

"The man said this: —Bertha, dear darling, this night will be the last of all the gloom and cloud which brood about thy young heart. To-morrow, dearest and best, the happy sunshine of your life begins. I have to meet the king at Kew at the hour of midnight, and he will with his own hands give me, by previous arrangement, a Treasury order payable to bearer for half a million of money. By eleven o'clock to-morrow morning that sum is to be paid without question or demur. We leave England then at once, sweetheart, and in a happy obscurity we shall begin to live indeed. Kiss me, my Bertha, and wish me good speed on my way. It will be the small hours of the morning before I look into your eyes again."

The thieves looked into each other's faces, and some shrank back to their seats.

The Ferret was silent.

"And—and what said the girl?" asked the captain.

The Ferret's eyes disappeared altogether. "It matters not what the girl said, but the man went on his errand. I saw him take a boat at the bridge steps to go up with the tide to Kew. The girl is in the house, and—and—"

"Yes, Ferret?"

"He may return with the Treasury order for the half million."

"But—but it seems," said the captain, "altogether so incredible."

"I have repeated what I heard," said the Ferret.

"And as there is a—a— Well, I need not use asseverations, but I believe it."

"Half a million!" exclaimed the thieves in chorus.

"What's the plot, Ferret?" asked the captain.

"It seems to me that—that we should be in the house when the man comes back, and—and meet him in the house. And as the—the young girl has a voice, and as we all know girls scream—scream, and make а half a million alarms in half a minute, why—why— why—why—I— I—yes I leave it to you, noble captain, and to you gentlemen all. I leave it to you." "But what do you mean, Ferret?"

"I don't—say—you must—murder the girl, but if dead men tell no tales, why dead girls don't scream. But I leave it to you, gentlemen all —I leave it to you, noble captain. I am the Ferret—only the Ferret. I spring the lay—I take my share—my share of half a million."

The Ferret held his hands above his head as he spoke, as if he expected the half million to descend in a golden shower upon him.

"We shall be all princes, nobles, made men," cried the captain. "Half a million among us! Why, it's thousands upon thousands upon thousands each! Tens of thousands upon tens of thousands."

"It is," said a rakish-looking individual in faded finery. "It is, but sink me if I like to kill the girl."

"But how would you," interrupted the Ferret, with a quick angry glance at the speaker, "how would you do it?"

"Oh, like men of courage— like honourable gentlemen. Sink me if I like to do anything in a sneaking way. Bah! No! I propose that about five of us lie in wait for the man in the roquelaire, and set on him all at once, and finish him before he gets into the house. I like to do things in a bold manly way. Sink me!"

"Very bold and manly," said the Ferret.

"To be sure; and then, if the girl is pretty, as you say, Why here am I, Jack Linton, always at the service of the fair. Sink me!"

"There is one objection," interposed the Ferret. "Nay, here am I—"

"Silence[!]" cried the captain. "Hear the Ferret."

"The row in the street—the fight—the public character of the neighbourhood. And I, for one, would scarcely wish to come within the length of the arm, with probably a sword at the end of it, of that man in scarlet with the roquelaire."

"Well, but you could come in a manly straight-

p. 19

forward manner behind him, and so finish him—pink him between the ribs—sa—sa—and away he goes."

"Will you be quiet," cried the captain, "and let the Ferret speak?"

The Ferret licked his lips again nervously.

"From what I heard the girl say, I am quite sure she will be waiting for the man at the door or window, and then she will scream. Oh, how she will scream! All Westminster will hear her, and you will have to kill her then."

There was a death-like stillness in the thieves' cellar.

"I'll tell you what I'd do, gentlemen, if I were you," said a voice.

The thieves and the Ferret raised a shout of alarm, and, turning in dismay, they saw standing coolly at the half-drawn aside blanket the tall interloper who had so recently made his escape after the very signal and mysterious discomfiture of big Peter.

"Yes, gentlemen," he added, "I'll tell you what I'd do if I were you."

"What?" screamed the Ferret.

"I'd give it up."

Bang! went a pistol shot, as the Ferret, levelling in a very hazardous manner past the eyes of the very straightforward and manly Jack Linton, fired at the stranger.

The blanket was dropped.

"Good night," said a voice. "I owe you one, Master Ferret."

There was a rush to the entrance of the cellar, but the stranger was gone, and had left not the slightest trace of his presence behind him.

Then the Ferret turned with gleaming eyes to the thieves, and spoke in harsh tones.

"If this thing is to be done, it must be done at once. Hark!"

The Abbey clock struck one.

CHAPTER VI.

A NIGHT ATTACK.

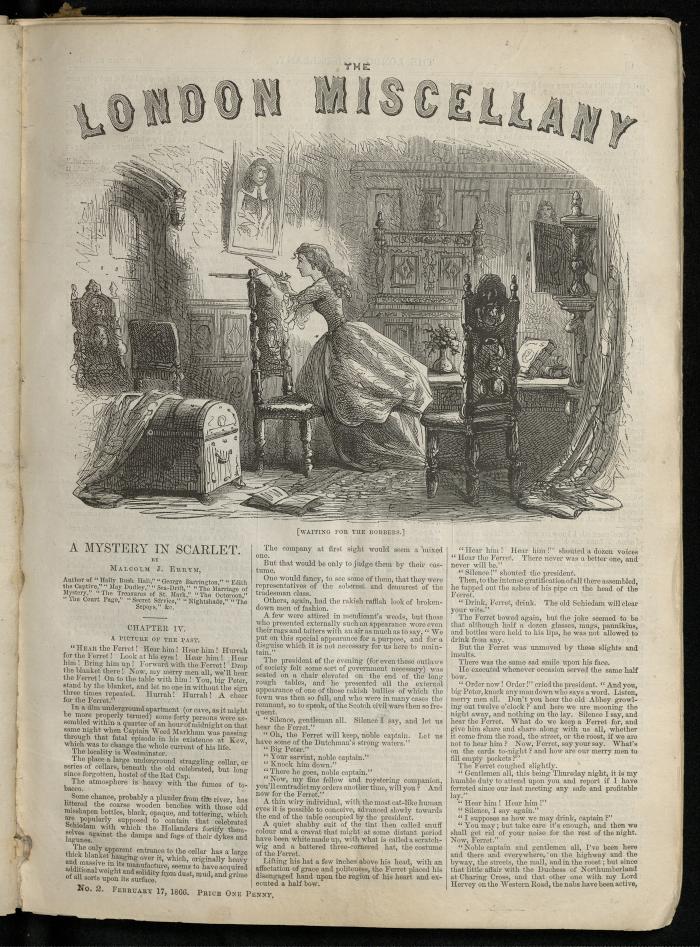

She was reading, but tears fell on the open page, and blurred and misty appeared the printed characters before her, for her mind was far away, travelling through many regions, and in too dim light of that solitary chamber, with darkening shadows in all its corners and piled up high above the Gothic fretwork of its ceiling, the fancy of that fair young creature was in the sunny South, where like other flowers she had blossomed and revelled in the sunshine.

The room is worth a passing glance, but its occupant is worth a hundred.

An antique chamber, once, no doubt, the glory and pride of a household, rich in carving at a period when that style of decoration was a fashion and a rage; the casements hung with heavy cloth curtains, which reposed on the floor in massive folds; a few old paintings set into the panels of the walls; the floor partially covered with one of those squares of rich tapestry that had made their way from Flanders; several antique black oaken cabinets; some tall straight-backed chairs covered with the veritable Utrecht velvet, but otherwise hard and angular; several tables with scattered books and papers upon them, and one in particular, small and unique of its kind, on which was a common earthen jar containing some ordinary flowers, and a book.

There sat the young girl.

Reading? reading? No.

Trying to read? Scarcely that.

It was not the word-painting of the old romance that lay open before her that brought those tears welling up from her heart to her eyes.

It was no fanciful woe of a fanciful hero or heroine that stirred her to such a passion of tears.

The book might have been far away in the dim clouds that hovered over the great city and the silent rolling river at hand for all she thought of it.

The past and the present were struggling for supremacy in that young heart, and the mortal frame was shaken in the contest of a thousand fears.

There was little need to shade the one dim light from the fair young eyes; but yet one hand, with its long slender fingers, rested lightly on her brow, screen-like and semi-transparent, as through the trembling fingers the light gleamed fitfully.

But now she removes that hand, and she lets it drop upon the other, which for the last few moments has rested upon the open page of the book.

She looks up.

We can see her face now.

Is she quite mortal?

Is there not something about the beauty more rare, spiritual, and unworldlike than can really belong to frail humanity?

What is it that is so entrancing about the face of the young girl, almost a child as she is?

Is it the beautiful contour of the rounded lines which enclose it, and seem to melt one into another in imperceptible curves of loveliness, dazzling the eyes to discover where actual outline ends and something more ethereal, beautiful, and insubstantial begins.

Are the eyes so very sweet in their dove-like expression that to them alone we are to look for the charm that pervades all around them?

Or is it the fair hair, with just the warm tinge, as though a morning sun had glistened upon it and left some of its scattered rays of gold to abide there for ever?

No. It is none of those things that make up the beaming loveliness of that face, but it is the expression—the singleness of expression, if we may so term it—of perfect innocence, ingenuousness, and purity that constitutes the charm more exquisite than any beauty of eyes, form, or colour.

And so, with those delicate child-like hands reposing upon each other on the open volume, this young girl looks up and peoples the thick shadows of the room with teeming fancies.

The long eyelashes are draped in tears.

She sighs as one so young and pure of heart can only sigh while earth's mists are about her.

And the silence, the deep impenetrable silence, of the house seems to combine with the darkness and to oppress her with an unknown terror.

She must speak.

It may be that the sound of her own voice will dispel some of the imaginative fears that are crowding about her.

But before she speaks she rises gently—and so fair, so delicate, so fragile, so angelically beautiful is she that when so rising, were she to exhale, so to speak, into the night air, and fade through the old blackened wainscote, one might be content to say that some pure spiritual essence had made a passing visit, for some holy purpose, to that apartment, and then winged its way heavenward again.

But it is a mortal sob that comes from her lips.

And now she touches a spring in one of the old panels of the room, and two small narrow doors open. She kneels before the emblem of her faith, and so we see that that fair young creature belongs to the Church of another clime than this.

She repeats an evening prayer, and then she closes the panels again, and the heart is stilled and less anxious.

"Oh, why did I let him go to-night?" she murmurs gently. "Why did I let him go to-night, and alone? What wild words were those he spoke to me of heaps of treasure with which we were to go back to our dear home among the vines and orange blossoms?"

She shuddered and folded her arms closely over her breast.

"All is so cold and cheerless. Why did I let him go? Could we not live in happiness, in poverty, and in peace? And yet he seemed so hopeful, so full of a strange joy. Father, Father, will this indeed be as you wish, and will this pilgrimage indeed be ended? Yes, he was very hopeful, he had no doubts, no fears. He spoke with unerring confidence, and yet— and yet— why did I let him go?"

She paused and listened.

The old Abbey clock was chiming the three-quarters past the midnight hour.

"A weary time! a weary time!" she murmured.

"These flowers are dumb, and cannot speak to me, and this book speaks a dumb language too, for it touches not the heart. Father, father, you have left me many an hour before, but I never seemed to yearn for you as I do now."

She sat down on one of the tall-backed chairs and rested her head upon her hands.

"We were happy. When was it? Oh, so long ago! And yet when I say so my poor father smiles at my words and tells me that long ago cannot enter into my comprehension; but it seems— it seems ages— ages— and the many mists of time appear to roll between my eyes and the vine-clad hills, the flower-strewn valleys, the golden sunlight, and our home upon the crag, with all its ancient battlements, its towers, its turrets, its mysteries, its shadows, and its sunlit terraces. Oh, it was long ago— long ago!"

With clasped hands, she rose and paced the room.

"I too will hope — I too will hope. I will think only of the joy that gleamed in his eyes when he spoke to me— 'Darling, we shall be rich and happy; and so good bye, sweetheart.' Was it not that, or something near to that? And yet— and yet I wish I had not let him go."

She stretched out her arms as she spoke, as though by that action, let him be where he might, she could draw him to her heart and hold him there against all danger.

The Abbey clock strikes one.

She presses back the clustering hair from her brow.

"I must try to read— I must try to think that he will come soon, and, until he does so, cheat the time of its weariness. We two are alone in the world together, and yet. what company we are! How lonely the poor heart may be in throngs and crowds! while what a pleasant joyous company it is to hold delightful converse with the one dear soul that loves us! Father, world, all, everything to me, oh! come back to me soon, for I'm very weary."

She sat down again.

Again she shaded her eyes from the dim light, but the disengaged hand only played with the leaves of the book, and far away her thoughts wandered again to things not present.

"What is that?"

She listens.

The startled attitude, the slightly inclined head, and the half movement to rise from the chair are sufficient evidences that some strange sound has struck upon her senses.

"What is that?"

She looks up to the ceiling, for the sound seems to have come from overhead, and, holding up one hand, in an attitude as though she would say, "Be still," although no living thing was in that apartment but herself, she listens until the strained sense becomes painful.

"It is nothing, and yet I thought I heard a sound, and but that I know that this house is empty and deserted I could have fancied a footstep echoing through the rooms above."

"Hush!"

There is something now.

A sharper sound, as if something had fallen on the floor in the apartment immediately overhead—some thing light and slight in construction, but still sufficient, in the deep silence of that mansion, to seem to strike an audible blow upon the floor above.

That could not be fancy.

Bertha turned very pale— white we might almost say — and for a moment, the old dim apartment in which she sat seemed to whirl around her.

That was perhaps the premonitory feeling of fainting, but it passed away, and as the colour slowly revisited her cheeks and lips she whispered to herself,

"Courage! Courage! Courage!"

And still she listened.

Creak! creak! creak!

That was overhead again.

A footstep, and then all was still.

"Father, Father, where are you now? Help! Help me! Let me think. What did you say to me?—what did you tell me? If ever I wanted aid, or if danger approached me in any of your absences, I was to bethink me that I was your daughter, and that you had been a soldier— that nothing immortal could or would harm me — that nothing mortal without the element of cowardice, which makes it weak, would dream of doing so, and that I might and should protect myself. Courage! Courage! Courage!"

Still listening, she moved towards the door.

It was of massive old Spanish mahogany, and moved lightly and easily upon its hinges.

She peered out into the darkness— the darkness of a corridor, and of a dim shadowy staircase springing from it.

She whispers the two words "courage" and "father" to herself, and then she lets the heavy old door swing to behind her.

The darkness in the corridor is now profound, since the few faint rays from the light in the room are shut away, and Bertha moves gently onward, feeling her way through the thick black shadows until she reaches the foot of the staircase.

She pauses, and now indeed is the time to whisper courage to herself and to invoke the name of that father who is far away.

A flickering ray of light comes straggling down the old oaken staircase, and, concentrating itself into a wide circle some three or four feet in diameter, it seems to be peering and prying about like a living thing into all odd corners and aim and dusky recesses.

It is evidently the light from the lens of a lantern.

Another moment, and it may fall upon the shrinking figure of Bertha; but the commencement of the balustrade of the staircase where she stands is very large and elaborate, and there is a carved lion rampant resting its huge forepaws upon a shield emblazoned with the arms of the family originally owning the house, and so Bertha has no difficulty in sinking down and hiding herself from the obtrusive glare of the lantern.

"Come on."

That was in a whispered voice from above.

"Shut up the lantern."

"Not I. I won't break my neck down these old stairs."

"Don't speak so loud, then, or we may alarm the girl, and if she once begins howling and screaming, there's an end of us."

"That's good advice," said another voice, "and of course our object should be to do the business in a straightforward English manly manner, by trying to knock her on the head before she has time to object."

"Will you be quiet, all of you?" growled the first speaker. The round spectrum from the lantern was far away from Bertha, and with a swift rush she was back into the room again, and pressing her hands upon her heart to still its beating.

Now she felt all her danger.

Worse than danger, for it shaped itself into the terrible word "murder!"

All the obscure hints that from time to time had fallen from her father's lips regarding the mysteries that surrounded them, and the danger that over hovered near them, came to her memory now with new significance. There were people, be they whom they might, intent upon their destruction. That was why her father had told her to have courage to defend herself. That was why he had placed the means in her hand of so doing. Ah, yes, those means! She had forgotten them. She was not alone, then— not quite alone. Mortal cowardice was about to attack her, and she had arms, and she had courage.

p. 20

She flew to one of the old cabinets.

With anxious eagerness she wrenched aside its fastenings.

One, two, three drawers she opens with trembling speed, and from the third she grasps a pair of rather large and heavy silver-mounted pistols.

She has courage, but it is not in human nature but that the nerves should thrill and jangle under such circumstances, and so the heavy silver ornamentation of the pistols sharply rattles against each other.

It was quite a picture.

That antique cabinet, with its heavy carved doors flung wide, and that young, fair, and gentle-looking girl, with the costly arms in her hands, in the attitude of a very listening statue, with her eyes bent upon the door of the apartment, expecting each moment it would open and Murder show itself in all its horrors.

One minute, two minutes pass, and still they come not.

She has time yet to take another precaution for security.

She flies to the door. The key is in the lock, and one movement is sufficient to turn it.

The obstacle may not be much against those who have made their way into the house to seek her life, but it is something, and time, even in its most limited degree, may make the difference between life and death.

"Courage! Courage! Courage still! This is what my father meant— this is what he thought might happen. He could not always take me with him, and he could not always remain with me, and so for this he has armed me, and told me to be worthy of him and protect myself for him. For him!"

She took her station at the further end of the apartment opposite to the massive door.

She knelt upon one of the chairs, the back of which was sufficiently low for her to see over it, and, resting and steadying the two pistols along the rich carved flowers of the framework of the chair, she looked past the one waxlight, which was dimly burning, and fixed her gaze upon the door.

That was another picture.

She heard the rain pattering without.

She heard the wind come in gusty rushes past the windows, for the tempestuous squall that swept over Kew Gardens that night likewise involved London in its fury.

But there was no difficulty in disentangling those natural noises without from any that might take place within the house.

Some three minutes more might have elapsed when there was a gentle rap on the other side of the door, as though some person with the most peaceful thoughts and intentions in the world required admission.

The rap was repeated again and again, and poor Bertha was compelled to close her eyes at intervals, for the steady gaze with which she regarded the door was apt to become painful, and the intense expectation that it would move and open more than once begat the idea that it was doing so.

The wonderful manner, however, in which real impressions supersede and scatter false ones could never be better exemplified than when on this occasion an actual effort was made from without to open the door.

Bertha had several times fancied the lock had moved, and now, and only now, she was quite sure of it.

She drew a long breath of relief, for the door resisted well, and each fleeting moment was she not gaining that time which was hope and life?

The rain and the wind paused for a brief period, and during that lapse she heard the Abbey clock again.

It was half-past one.

Now there is a grating sound at the door.

As silently as may be the invaders are seeking to overcome the resistance of the lock.

Scrape, scrape, scrape.

The key surely defeats them in some way, lost as it is in the wards, and the light is too dim at that distance to let Bertha see that that key is slowly turning until it assumes a vertical position.

Then she cannot suppress a short sharp cry.

The key is suddenly thrust out of the lock, and falls upon the floor.

Bertha's finger is upon the trigger of one of the pistols.

Surely the time for action has arrived.

"Father! father!" she cries. "Help me! Help me! for I have courage, and I obey you by striving to help myself."

She closes her eyes.

No; that is not courageous. She must see where to level the pistol, and where to fire. She fixes a steady gaze upon the door. She does not reflect whether or not the bullet will pierce its massive panels, but the crisis seems to her to have arrived to show that she has heart, means, and will to defend herself.

She fires.

(To be continued in our next.)

A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER IV.

A PICTURE OF THE PAST.

"Hear the Ferret! Hear him! Hear him! Hurrah for the Ferret! Look at his eyes! Hear him! Hear him! Bring him up! Forward with the Ferret! Drop the blanket there! Now, my merry men all, we'll hear the Ferret! On to the table with him! You, big Peter, stand by the blanket, and let no one in without the sign three times repeated. Hurrah! Hurrah! A cheer for the Ferret."

In a dim underground apartment (or cave, as it might be more properly termed) some forty persons were assembled within a quarter of an hour of midnight on that same night when Captain Weed Markham was passing through that fatal episode in his existence at Kew, which was to change the whole current of his life.

The locality is Westminster.

The place a large underground straggling cellar, or series of cellars, beneath the old celebrated, but long since forgotten, hostel of the Red Cap.

The atmosphere is heavy with the fumes of tobacco.

Some chance, probably a plunder from the river, has littered the coarse wooden benches with those odd misshapen bottles, black, opaque, and tottering, which are popularly supposed to contain that celebrated Schiedam with which the Hollanders fortify themselves against the damps and fogs of their dykes and lagunes.

The only apparent entrance to the cellar has a large thick blanket hanging over it, which, originally heavy and massive in its manufacture, seems to have acquired additional weight and solidity from dust, mud, and grime of all sorts upon its surface.

The company at first sight would seem a mixed one.

But that would be only to judge them by their costume.

One would fancy, to see some of them, that they were representatives of the soberest and demurest of the tradesman class.

Others, again, had the rakish raffish look of broken-down men of fashion.

A few were attired in mendicant's weeds, but those who presented externally such an appearance wore even their rags and tatters with an air as much as to say, "We put on this special appearance for a purpose, and for a disguise which it is not necessary for us here to maintain."

The president of the evening (for even these outlaws of society felt some sort of government necessary) was seated on a chair elevated on the end of the long rough tables, and he presented all the external appearance of one of those rakish bullies of which the town was then so full, and who were in many cases the remnant, so to speak, of the Scotch civil wars then so frequent.

"Silence, gentleman all. Silence I say, and let us hear the Ferret."

"Oh, the Ferret will keep, noble captain. Let us have some of the Dutchman's strong waters."

"Big Peter."

"Your sarvint, noble captain."

"Knock him down."

"There he goes, noble captain."

"Now, my fine fellow and roystering companion, you'll contradict my orders another time, will you? And now for the Ferret."

A thin wily individual, with the most cat-like human eyes it is possible to conceive, advanced slowly towards the end of the table occupied by the president.

A quiet shabby suit of the tint then called snuff colour and a cravat that might at some distant period have been white made up, with what is called a scratch wig and a battered three-cornered hat, the costume of the Ferret.

Lifting his hat a few inches above his head, with an affectation of grace and politeness, the Ferret placed his disengaged hand upon the region of his heart and executed a half bow.

"Hear him! Hear him!" shouted a dozen voices. "Hear the Ferret. There never was a better one, and never will be."

"Silence!" shouted the president.

Then, to the intense gratification of all there assembled, he tapped out the ashes of his pipe on the head of the Ferret.

"Drink, Ferret, drink. The old Schiedam will clear your wits."

The Ferret bowed again, but the joke seemed to be that although half a dozen glasses, mugs, pannikins, and bottles were held to his lips, he was not allowed to drink from any.

But the Ferret was unmoved by these slights and insults.

There was the same sad smile upon his face.

He executed whenever occasion served the same half bow.

"Order now! Order!" cried the president. "And you, big Peter, knock any man down who says a word. Listen, merry men all. Don't you hear the old Abbey growling out twelve o'clock? and here we are mooning the night away, and nothing on the lay. Silence I say, and hear the Ferret. What do we keep a Ferret for, and give him share and share along with us all, whether it come from the road, the street, or the roost, if we are not to hear him? Now, Ferret, say your say. What's on the cards to-night? and how are our merry men to fill empty pockets?"

The Ferret coughed slightly.

"Gentlemen all, this being Thursday night, it is my humble duty to attend upon you and report if I have ferreted since our last meeting any safe and profitable lay."

"Hear him! Hear him!"

"Silence, I say again."

"I supposes as how we may drink, captain?"

"You may; but take care it's enough, and then we shall get rid of your noise for the rest of the night. Now, Ferret."

"Noble captain and gentlemen all, I've been here and there and everywhere, on the highway and the byway, the streets, the mall, and in the roost; but since that little affair with the Duchess of Northumberland at Charing Cross, and that other one with my Lord Hervey on the Western Road, the nabs have been active,

p. 18

and I wouldn't advise any good friend of mine to look for sport in that way just now. But—"

"Well, Ferret—but?"

"There's a roosting game, which, good friends all, you know means that there is something to be done within four walls while somebody else sleeps."

The Ferret spoke in so mysterious and low a tone that every head was inclined towards him to catch what he said.

The noble captain, as the gentleman in the chair was styled, even put down his pipe and listened.

"Well, Ferret, what is it?"

"It's something I've been at for weeks and weeks, but if it's half, or a quarter, or half a quarter, or half or a tenth of that again what it seems to be, you are all made men."

"No!"

"Yes, noble captain and gentlemen all."

"Out with it, Ferret. Out with it."

"Drink, Ferret, drink."

"No, no. This is no time to drink, and it's so strange a story, noble captain and gentlemen all, that I for one should like to know and feel sure—"

"Sure of what, Ferret?"

"Why, that we're all good men and true here."

"Ah, yes."

A glass was accidentally broken at one of the tables.

"Silence!" cried the captain. "You big Peter, keep the blanket. Our Ferret is an old hound, and don't give tongue till he sees the game."

"Bravo! bravo! Hear him! Hear him!"

The captain waved his hand authoritatively for silence.

"I don' t mean to say for a moment, gentlemen," added the Ferret, "nor is it at all likely any one is here present that don't belong to the honourable family, but this little affair, noble captain and gentlemen, is a matter of life and—and—"

"And what, Ferret?"

"Death!"

The Ferret's eyes seemed to look two ways at once as he uttered this word, and his thin lips curled inward more than before.

"Let every man," said the captain, speaking with deliberation, "let every man here present walk past me, between the back of my chair and the wall. There's just room enough. And as he does so he can whisper to me the word which makes us good fellows all and hail, well met."

"Bravo! bravo! Hear the noble captain. That's the way."

The whole party tumultuously rose, with the exception of one man.

A tall muscular-looking individual in a faded scarlet coat with heavy lappels, and a cravat the loose ends of which were ostentatiously tucked in at one portion of his waistcoat and projected from the other, suddenly thrust back the rough stool on which he sat until he reached the wall, and then, in a calm steady voice, he spoke—

"Gentlemen all, I know no words, for this is no crib of mine. I hunt the highway, the common, and the heath, and my horse is at the Chequers. I know no words, I say, but if blows will do as well, I'm ready for any couple of you at a moment's notice."

A roar of execration burst from the assembled thieves, and it was with difficulty the captain commanded silence.

Some threatening gestures were made at the stranger, and one or two knives gleamed from secret receptacles.

"Ware hawk, if you please, gentlemen," added the stranger. "Wherever I go there are generally three of us. I'm one, and these two little pop-guns are the other two."

As he spoke the stranger presented a couple of pistols in an easy nonchalant manner, but in such a direction that were he to discharge them they would inevitably take effect upon the president and the Ferret.

The latter shrank back, and the president in an absurd way held out his pipe, as if with the bowl of it he could intercept the shot.

"Tush, man! tush!" he cried. "Put up those pops, and just say how you саmе here."

"With all my heart. Ned Forrester, the mighty good host of the Red Cap, showed me the other side of yonder blanket, and I suppose vouched for me to your ugly giant there, Peter, as you call him."

The thieves looked in each other's faces irresolutely.

"Give him the oath," said the Ferret. "Make him one."

"Yes, yes. That's it. Make him one. Make him one."

"Fair and softly," said the stranger. "I strolled in here for a drink, a song, and a carouse, nothing more, and I am willing to go as I came, knowing nothing and therefore not in ease to betray anything."

"No, no!" cried a dozen voices.

The stranger rose and stepped towards the blanket.

"And why no?" he shouted. "Are you so fond, all of you, of being laid fast, and told you shan't go here or there, that you wish to make a caged bird of me? Now, Peter, I'll thank you to remove that bullock's hide of yours out of the way."

"Not if I know it," growled Peter. "Who are you, I should like to know, that—"

Peter terminated his growling speech with a yell that rang through the cellar, and with one tremendous leap he sprang into the midst of the thieves, who had hastily risen from the stools and benches.

"Good night," said the stranger.

The blanket was rapidly moved on one side and in another instant he was gone.

A dozen voices demanded of Peter what was the matter, but to the best of his belief he didn't know, except that a flame, a flash of lightning, or something red hot had begun to make its way in at his back as he stood on guard by the blanket.

And sure enough there was a small charred orifice in Peter's coat just between his shoulders, and a corresponding still smouldering minute aperture in the blanket.

But the stranger was gone.

"What does it matter, gentlemen all?" cried the captain. "He's off, be he whom he may, and he knows nothing."

"He looked a high-flyer," said the Ferret. "And as this is a roosting lay, we certainly don't want him."

"Drink, Ferret, drink."

"Water. I feel parched."

The captain shook his head.

"You won't get that here, Ferret; but are you content now that all here present are good and true family men?"

"I am now, and so, noble captain and gentlemen all, I want to ask you a question."

"Out with it, Ferret, and speak up."

"So, with all deference to you, this is not a matter to speak up about."

"Go on, then. Go on."

There came a faint flush of colour into the face of the Ferret, and his eyes seemed to describe concentric circles in their orbits.

"Do you, noble captain, or do any of you, or do all of you together think you can muster up a fair notion of what half a million of money means?"

"Half a million!"

"Half—a—million?"

"I have said it."

The captain placed his hand upon his brow.

"It's five hundred thousand all in gold. It's millions in smaller coin. It's—it's— You don't mean half million, Ferret?"

"I do."

The thieves drew long breaths and crowded in a strange motley throng about the upper end of the cellar. Even big Peter forsook his post at the blanket and approached to glare, in the eccentric eyes of the Ferret.

"Half a million?" repeated the latter. "And — and—"

"Hush! hush!"

Every man hushed down his neighbour.

The Ferret licked his lips, and nothing but the whites (if whites they could be called) of his eyes were visible.

"And only two lives in the way."

"Two lives?" murmured the thieves.

"Ferret," said the captain. "Aye."

"Must those two lives go?"

The Ferret nodded.

The thieves looked in each other's faces, and then the captain, as he gazed up at the begrimed ceiling of the cellar, muttered to himself, "Half a million. Half of ten hundred thousand. Ferret, you are mad."

CHAPTER V.

MURDER IN THE AIR.

The Ferret's eyes assumed another phase, which seemed to represent the small pupils in totally opposite corners.

"I am not mad, noble captain."

"Then speak out."

"I will. You know these are the cellars of the old Red Cap, where they say more crimes and conspiracies have been hatched for these last hundred years than in any other house in London."

"What of that, Ferret?"

"Not much. But next door some of you may know is the house where Sir Thomas Mears was murdered by the wild and profligate уoung Lord Overton. They called it a duel, and they do say that Lady Mears held up a couple of candles while they fought, and, when Sir Thomas was killed, drove off with the young lord, and sо the house was deserted until lately, when it has had two inhabitants."

"Well, Ferret?"

"A man with something of the look and carriage of a soldier. He usually wears a faded roquelaire cloak, and underneath, as I have accidentally seen it blown aside by the wind or carelessly worn, a scarlet coat."

"Well, Ferret?"

"The other person is a young girl."

"A young girl?"

"Yes. I should take her to be some fourteen or fifteen years of age. She is fair and—and—innocent and—and—"

"Well, Ferret?"

The Ferret drew a long breath.

"Half a million."

"But what do you mean by it? What do you mean by your half million, and your odd looks, and your man in scarlet with the roquelaire cloak, and your young girl? How does it all hang together, Ferret?"

"I will tell you. I am a Ferret, as you call me— the Ferret of this honourable company—that is to say, I insinuate myself into strange places—I listen—I lie in wait for information—I pry into secrets and ascertain the depositories of gold and valuables—I discover how they are guarded and by whom."

"Good," said the captain. "And many a rich lay you have put us on."

"But this," added the Ferret, "transcends them all."

He lowered his voice still more, as he spoke, until it had decreased almost to a whisper.

"Watching this man and the girl, and wondering who and what they were, I bethought me of getting out on the roof of the old Red Cap, and so seeing if I could make my way into the next house. It was not difficult, and light as a cat I dropped into one of the attics. Creeping then down the staircase, I heard voices, and in the large room at the back on the first floor I found that the man was speaking to the girl in such earnest tones of excitement that, crouching on the staircase, I heard all he said."

"Well, Ferret, and what was it?"

The Ferret licked his parched lips again, and then, half closing his eyes, as though by that process he could look with the other half back into his memory for the exact words he wished to repeat, he spoke slowly.

"The man said this: —Bertha, dear darling, this night will be the last of all the gloom and cloud which brood about thy young heart. To-morrow, dearest and best, the happy sunshine of your life begins. I have to meet the king at Kew at the hour of midnight, and he will with his own hands give me, by previous arrangement, a Treasury order payable to bearer for half a million of money. By eleven o'clock to-morrow morning that sum is to be paid without question or demur. We leave England then at once, sweetheart, and in a happy obscurity we shall begin to live indeed. Kiss me, my Bertha, and wish me good speed on my way. It will be the small hours of the morning before I look into your eyes again."

The thieves looked into each other's faces, and some shrank back to their seats.

The Ferret was silent.

"And—and what said the girl?" asked the captain.

The Ferret's eyes disappeared altogether. "It matters not what the girl said, but the man went on his errand. I saw him take a boat at the bridge steps to go up with the tide to Kew. The girl is in the house, and—and—"

"Yes, Ferret?"

"He may return with the Treasury order for the half million."

"But—but it seems," said the captain, "altogether so incredible."

"I have repeated what I heard," said the Ferret.

"And as there is a—a— Well, I need not use asseverations, but I believe it."

"Half a million!" exclaimed the thieves in chorus.

"What's the plot, Ferret?" asked the captain.

"It seems to me that—that we should be in the house when the man comes back, and—and meet him in the house. And as the—the young girl has a voice, and as we all know girls scream—scream, and make а half a million alarms in half a minute, why—why— why—why—I— I—yes I leave it to you, noble captain, and to you gentlemen all. I leave it to you." "But what do you mean, Ferret?"

"I don't—say—you must—murder the girl, but if dead men tell no tales, why dead girls don't scream. But I leave it to you, gentlemen all —I leave it to you, noble captain. I am the Ferret—only the Ferret. I spring the lay—I take my share—my share of half a million."

The Ferret held his hands above his head as he spoke, as if he expected the half million to descend in a golden shower upon him.

"We shall be all princes, nobles, made men," cried the captain. "Half a million among us! Why, it's thousands upon thousands upon thousands each! Tens of thousands upon tens of thousands."

"It is," said a rakish-looking individual in faded finery. "It is, but sink me if I like to kill the girl."

"But how would you," interrupted the Ferret, with a quick angry glance at the speaker, "how would you do it?"

"Oh, like men of courage— like honourable gentlemen. Sink me if I like to do anything in a sneaking way. Bah! No! I propose that about five of us lie in wait for the man in the roquelaire, and set on him all at once, and finish him before he gets into the house. I like to do things in a bold manly way. Sink me!"

"Very bold and manly," said the Ferret.

"To be sure; and then, if the girl is pretty, as you say, Why here am I, Jack Linton, always at the service of the fair. Sink me!"

"There is one objection," interposed the Ferret. "Nay, here am I—"

"Silence[!]" cried the captain. "Hear the Ferret."

"The row in the street—the fight—the public character of the neighbourhood. And I, for one, would scarcely wish to come within the length of the arm, with probably a sword at the end of it, of that man in scarlet with the roquelaire."

"Well, but you could come in a manly straight-

p. 19

forward manner behind him, and so finish him—pink him between the ribs—sa—sa—and away he goes."

"Will you be quiet," cried the captain, "and let the Ferret speak?"

The Ferret licked his lips again nervously.

"From what I heard the girl say, I am quite sure she will be waiting for the man at the door or window, and then she will scream. Oh, how she will scream! All Westminster will hear her, and you will have to kill her then."

There was a death-like stillness in the thieves' cellar.

"I'll tell you what I'd do, gentlemen, if I were you," said a voice.

The thieves and the Ferret raised a shout of alarm, and, turning in dismay, they saw standing coolly at the half-drawn aside blanket the tall interloper who had so recently made his escape after the very signal and mysterious discomfiture of big Peter.

"Yes, gentlemen," he added, "I'll tell you what I'd do if I were you."

"What?" screamed the Ferret.

"I'd give it up."

Bang! went a pistol shot, as the Ferret, levelling in a very hazardous manner past the eyes of the very straightforward and manly Jack Linton, fired at the stranger.

The blanket was dropped.

"Good night," said a voice. "I owe you one, Master Ferret."

There was a rush to the entrance of the cellar, but the stranger was gone, and had left not the slightest trace of his presence behind him.

Then the Ferret turned with gleaming eyes to the thieves, and spoke in harsh tones.

"If this thing is to be done, it must be done at once. Hark!"

The Abbey clock struck one.

CHAPTER VI.

A NIGHT ATTACK.

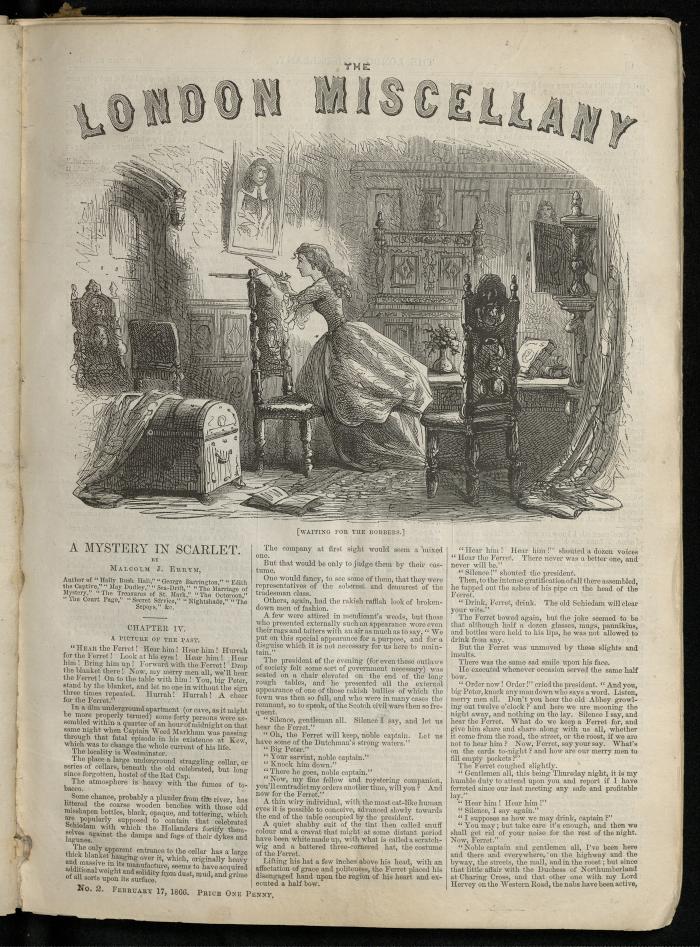

She was reading, but tears fell on the open page, and blurred and misty appeared the printed characters before her, for her mind was far away, travelling through many regions, and in too dim light of that solitary chamber, with darkening shadows in all its corners and piled up high above the Gothic fretwork of its ceiling, the fancy of that fair young creature was in the sunny South, where like other flowers she had blossomed and revelled in the sunshine.

The room is worth a passing glance, but its occupant is worth a hundred.

An antique chamber, once, no doubt, the glory and pride of a household, rich in carving at a period when that style of decoration was a fashion and a rage; the casements hung with heavy cloth curtains, which reposed on the floor in massive folds; a few old paintings set into the panels of the walls; the floor partially covered with one of those squares of rich tapestry that had made their way from Flanders; several antique black oaken cabinets; some tall straight-backed chairs covered with the veritable Utrecht velvet, but otherwise hard and angular; several tables with scattered books and papers upon them, and one in particular, small and unique of its kind, on which was a common earthen jar containing some ordinary flowers, and a book.

There sat the young girl.

Reading? reading? No.

Trying to read? Scarcely that.

It was not the word-painting of the old romance that lay open before her that brought those tears welling up from her heart to her eyes.

It was no fanciful woe of a fanciful hero or heroine that stirred her to such a passion of tears.

The book might have been far away in the dim clouds that hovered over the great city and the silent rolling river at hand for all she thought of it.

The past and the present were struggling for supremacy in that young heart, and the mortal frame was shaken in the contest of a thousand fears.

There was little need to shade the one dim light from the fair young eyes; but yet one hand, with its long slender fingers, rested lightly on her brow, screen-like and semi-transparent, as through the trembling fingers the light gleamed fitfully.

But now she removes that hand, and she lets it drop upon the other, which for the last few moments has rested upon the open page of the book.

She looks up.

We can see her face now.

Is she quite mortal?

Is there not something about the beauty more rare, spiritual, and unworldlike than can really belong to frail humanity?

What is it that is so entrancing about the face of the young girl, almost a child as she is?

Is it the beautiful contour of the rounded lines which enclose it, and seem to melt one into another in imperceptible curves of loveliness, dazzling the eyes to discover where actual outline ends and something more ethereal, beautiful, and insubstantial begins.

Are the eyes so very sweet in their dove-like expression that to them alone we are to look for the charm that pervades all around them?

Or is it the fair hair, with just the warm tinge, as though a morning sun had glistened upon it and left some of its scattered rays of gold to abide there for ever?

No. It is none of those things that make up the beaming loveliness of that face, but it is the expression—the singleness of expression, if we may so term it—of perfect innocence, ingenuousness, and purity that constitutes the charm more exquisite than any beauty of eyes, form, or colour.

And so, with those delicate child-like hands reposing upon each other on the open volume, this young girl looks up and peoples the thick shadows of the room with teeming fancies.

The long eyelashes are draped in tears.

She sighs as one so young and pure of heart can only sigh while earth's mists are about her.

And the silence, the deep impenetrable silence, of the house seems to combine with the darkness and to oppress her with an unknown terror.

She must speak.

It may be that the sound of her own voice will dispel some of the imaginative fears that are crowding about her.

But before she speaks she rises gently—and so fair, so delicate, so fragile, so angelically beautiful is she that when so rising, were she to exhale, so to speak, into the night air, and fade through the old blackened wainscote, one might be content to say that some pure spiritual essence had made a passing visit, for some holy purpose, to that apartment, and then winged its way heavenward again.

But it is a mortal sob that comes from her lips.

And now she touches a spring in one of the old panels of the room, and two small narrow doors open. She kneels before the emblem of her faith, and so we see that that fair young creature belongs to the Church of another clime than this.

She repeats an evening prayer, and then she closes the panels again, and the heart is stilled and less anxious.

"Oh, why did I let him go to-night?" she murmurs gently. "Why did I let him go to-night, and alone? What wild words were those he spoke to me of heaps of treasure with which we were to go back to our dear home among the vines and orange blossoms?"

She shuddered and folded her arms closely over her breast.

"All is so cold and cheerless. Why did I let him go? Could we not live in happiness, in poverty, and in peace? And yet he seemed so hopeful, so full of a strange joy. Father, Father, will this indeed be as you wish, and will this pilgrimage indeed be ended? Yes, he was very hopeful, he had no doubts, no fears. He spoke with unerring confidence, and yet— and yet— why did I let him go?"

She paused and listened.

The old Abbey clock was chiming the three-quarters past the midnight hour.

"A weary time! a weary time!" she murmured.

"These flowers are dumb, and cannot speak to me, and this book speaks a dumb language too, for it touches not the heart. Father, father, you have left me many an hour before, but I never seemed to yearn for you as I do now."

She sat down on one of the tall-backed chairs and rested her head upon her hands.

"We were happy. When was it? Oh, so long ago! And yet when I say so my poor father smiles at my words and tells me that long ago cannot enter into my comprehension; but it seems— it seems ages— ages— and the many mists of time appear to roll between my eyes and the vine-clad hills, the flower-strewn valleys, the golden sunlight, and our home upon the crag, with all its ancient battlements, its towers, its turrets, its mysteries, its shadows, and its sunlit terraces. Oh, it was long ago— long ago!"

With clasped hands, she rose and paced the room.

"I too will hope — I too will hope. I will think only of the joy that gleamed in his eyes when he spoke to me— 'Darling, we shall be rich and happy; and so good bye, sweetheart.' Was it not that, or something near to that? And yet— and yet I wish I had not let him go."

She stretched out her arms as she spoke, as though by that action, let him be where he might, she could draw him to her heart and hold him there against all danger.

The Abbey clock strikes one.

She presses back the clustering hair from her brow.

"I must try to read— I must try to think that he will come soon, and, until he does so, cheat the time of its weariness. We two are alone in the world together, and yet. what company we are! How lonely the poor heart may be in throngs and crowds! while what a pleasant joyous company it is to hold delightful converse with the one dear soul that loves us! Father, world, all, everything to me, oh! come back to me soon, for I'm very weary."

She sat down again.

Again she shaded her eyes from the dim light, but the disengaged hand only played with the leaves of the book, and far away her thoughts wandered again to things not present.

"What is that?"

She listens.

The startled attitude, the slightly inclined head, and the half movement to rise from the chair are sufficient evidences that some strange sound has struck upon her senses.

"What is that?"

She looks up to the ceiling, for the sound seems to have come from overhead, and, holding up one hand, in an attitude as though she would say, "Be still," although no living thing was in that apartment but herself, she listens until the strained sense becomes painful.

"It is nothing, and yet I thought I heard a sound, and but that I know that this house is empty and deserted I could have fancied a footstep echoing through the rooms above."

"Hush!"

There is something now.

A sharper sound, as if something had fallen on the floor in the apartment immediately overhead—some thing light and slight in construction, but still sufficient, in the deep silence of that mansion, to seem to strike an audible blow upon the floor above.

That could not be fancy.

Bertha turned very pale— white we might almost say — and for a moment, the old dim apartment in which she sat seemed to whirl around her.

That was perhaps the premonitory feeling of fainting, but it passed away, and as the colour slowly revisited her cheeks and lips she whispered to herself,

"Courage! Courage! Courage!"

And still she listened.

Creak! creak! creak!

That was overhead again.

A footstep, and then all was still.

"Father, Father, where are you now? Help! Help me! Let me think. What did you say to me?—what did you tell me? If ever I wanted aid, or if danger approached me in any of your absences, I was to bethink me that I was your daughter, and that you had been a soldier— that nothing immortal could or would harm me — that nothing mortal without the element of cowardice, which makes it weak, would dream of doing so, and that I might and should protect myself. Courage! Courage! Courage!"

Still listening, she moved towards the door.

It was of massive old Spanish mahogany, and moved lightly and easily upon its hinges.

She peered out into the darkness— the darkness of a corridor, and of a dim shadowy staircase springing from it.

She whispers the two words "courage" and "father" to herself, and then she lets the heavy old door swing to behind her.

The darkness in the corridor is now profound, since the few faint rays from the light in the room are shut away, and Bertha moves gently onward, feeling her way through the thick black shadows until she reaches the foot of the staircase.

She pauses, and now indeed is the time to whisper courage to herself and to invoke the name of that father who is far away.

A flickering ray of light comes straggling down the old oaken staircase, and, concentrating itself into a wide circle some three or four feet in diameter, it seems to be peering and prying about like a living thing into all odd corners and aim and dusky recesses.

It is evidently the light from the lens of a lantern.

Another moment, and it may fall upon the shrinking figure of Bertha; but the commencement of the balustrade of the staircase where she stands is very large and elaborate, and there is a carved lion rampant resting its huge forepaws upon a shield emblazoned with the arms of the family originally owning the house, and so Bertha has no difficulty in sinking down and hiding herself from the obtrusive glare of the lantern.

"Come on."

That was in a whispered voice from above.

"Shut up the lantern."

"Not I. I won't break my neck down these old stairs."

"Don't speak so loud, then, or we may alarm the girl, and if she once begins howling and screaming, there's an end of us."

"That's good advice," said another voice, "and of course our object should be to do the business in a straightforward English manly manner, by trying to knock her on the head before she has time to object."

"Will you be quiet, all of you?" growled the first speaker. The round spectrum from the lantern was far away from Bertha, and with a swift rush she was back into the room again, and pressing her hands upon her heart to still its beating.

Now she felt all her danger.

Worse than danger, for it shaped itself into the terrible word "murder!"

All the obscure hints that from time to time had fallen from her father's lips regarding the mysteries that surrounded them, and the danger that over hovered near them, came to her memory now with new significance. There were people, be they whom they might, intent upon their destruction. That was why her father had told her to have courage to defend herself. That was why he had placed the means in her hand of so doing. Ah, yes, those means! She had forgotten them. She was not alone, then— not quite alone. Mortal cowardice was about to attack her, and she had arms, and she had courage.

p. 20

She flew to one of the old cabinets.

With anxious eagerness she wrenched aside its fastenings.

One, two, three drawers she opens with trembling speed, and from the third she grasps a pair of rather large and heavy silver-mounted pistols.

She has courage, but it is not in human nature but that the nerves should thrill and jangle under such circumstances, and so the heavy silver ornamentation of the pistols sharply rattles against each other.

It was quite a picture.

That antique cabinet, with its heavy carved doors flung wide, and that young, fair, and gentle-looking girl, with the costly arms in her hands, in the attitude of a very listening statue, with her eyes bent upon the door of the apartment, expecting each moment it would open and Murder show itself in all its horrors.

One minute, two minutes pass, and still they come not.

She has time yet to take another precaution for security.

She flies to the door. The key is in the lock, and one movement is sufficient to turn it.

The obstacle may not be much against those who have made their way into the house to seek her life, but it is something, and time, even in its most limited degree, may make the difference between life and death.

"Courage! Courage! Courage still! This is what my father meant— this is what he thought might happen. He could not always take me with him, and he could not always remain with me, and so for this he has armed me, and told me to be worthy of him and protect myself for him. For him!"

She took her station at the further end of the apartment opposite to the massive door.

She knelt upon one of the chairs, the back of which was sufficiently low for her to see over it, and, resting and steadying the two pistols along the rich carved flowers of the framework of the chair, she looked past the one waxlight, which was dimly burning, and fixed her gaze upon the door.

That was another picture.

She heard the rain pattering without.

She heard the wind come in gusty rushes past the windows, for the tempestuous squall that swept over Kew Gardens that night likewise involved London in its fury.

But there was no difficulty in disentangling those natural noises without from any that might take place within the house.

Some three minutes more might have elapsed when there was a gentle rap on the other side of the door, as though some person with the most peaceful thoughts and intentions in the world required admission.

The rap was repeated again and again, and poor Bertha was compelled to close her eyes at intervals, for the steady gaze with which she regarded the door was apt to become painful, and the intense expectation that it would move and open more than once begat the idea that it was doing so.

The wonderful manner, however, in which real impressions supersede and scatter false ones could never be better exemplified than when on this occasion an actual effort was made from without to open the door.

Bertha had several times fancied the lock had moved, and now, and only now, she was quite sure of it.

She drew a long breath of relief, for the door resisted well, and each fleeting moment was she not gaining that time which was hope and life?

The rain and the wind paused for a brief period, and during that lapse she heard the Abbey clock again.

It was half-past one.

Now there is a grating sound at the door.

As silently as may be the invaders are seeking to overcome the resistance of the lock.

Scrape, scrape, scrape.

The key surely defeats them in some way, lost as it is in the wards, and the light is too dim at that distance to let Bertha see that that key is slowly turning until it assumes a vertical position.

Then she cannot suppress a short sharp cry.

The key is suddenly thrust out of the lock, and falls upon the floor.

Bertha's finger is upon the trigger of one of the pistols.

Surely the time for action has arrived.

"Father! father!" she cries. "Help me! Help me! for I have courage, and I obey you by striving to help myself."

She closes her eyes.

No; that is not courageous. She must see where to level the pistol, and where to fire. She fixes a steady gaze upon the door. She does not reflect whether or not the bullet will pierce its massive panels, but the crisis seems to her to have arrived to show that she has heart, means, and will to defend herself.

She fires.

(To be continued in our next.)