A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER VII.

RESCUE OR NO RESCUE.

The report of the pistol fired by Bertha awakened a thousand echoes in the old apartment, and mingling with them was a sharper shattering sound, as though some panes of glass by the concussion of the air had given way in one of the compartments of the large casements.

The bullet embedded itself deeply in one of the panels of the mahogany door.

And then, as the sharp detonations of the explosion died away, Bertha could dimly see, through wreaths of white vapour making their way up to the ceiling of the apartment, that she was still alone.

What effect had that pistol-shot had?

Were her enemies scared from further attacks upon that massive ancient door?

Was she to gain from their fears those few precious minutes which might, and she thought surely must, bring her aid and safety?

These were heart-sickening questions for her to ask herself in such a moment.

But the scraping noise outside the door had ceased.

The house was very still again.

And in imagination that young creature, straining her sense of sight, in her intense desire to know if her foes had abandoned the attack, seemed as though she could do more even than the pistol bullet, and pierce with her gaze the massive panels of that door, to see into the shadowy sрасе beyond.

And this delusion grew upon her.

The door seemed at moments to melt away from her sight, and in its place appeared angry and ferocious countenances, and shadowy arms using menacing gestures.

These were the results of an over-excited brain and a too sensitive organisation.

She had but to close her eyes for a moment to take off the strain upon them, and those visions would vanish. The massive mahogany door would shape itself again into its place, and Bertha would once more feel that she was yet safe.

She still kept the pistols in the same attitude, balanced among the intricacies of the carved back of the old chair, and she was hardly able to explain to herself for a time why it was that the light in the room was of so different a character from what it had been.

The fact was that the concussion of air from the pistol-shot, besides shattering two or three panes of glass, had extinguished the only light in the apartment, and the dim twilight-looking radiance that found its way there came from a street lamp not many paces from the front of the house.

And now the lips of the young girl moved, as in whispered accents she called again upon that father who was past all invocations, even from that dear heart, in this world.

Moments swelled themselves into hours of anguish, and if it were possible that one hour could have passed away while Bertha thus listened and trembled between life and death, that hour would have indeed concentrated in its brief career an age of terror.

What were they doing?

Why were they making such strange hissing noises on the other side of the door?

That was but the subdued murmur of their conversation.

Why were they there so still? And was that slight rattling sound that occasionally only broke the stillness a signal of their departure or not?

And so time wore on through one of its briefest spaces, and then the sharpened senses of the young girl made her cognisant of a fresh alarm, since everything that was new or strange, be it a voice or any other disturbance of the stillness about her, came to her perception only in a threatening aspect.

It was a voice.

"I will stretch down my arms, and you'll have no difficulty then in making your way into the balcony."

Very clearly spoken were those words, and yet in so low a tone that they seemed a long way off. Somewhere in the air?—above?—below?—where were they?

A dreary feeling of utter desolation crept across the heart of poor Bertha, for as the voice spoke again she was able to define where it was, to localise its precise position, and in doing so hope died away, and she told herself she was indeed lost.

The voice came from just without the ancient casement—from some one doubtless in that balcony which ran along the front of the house; and the idea of its far distant sound had probably arisen from the fact that the person, whoever he was, had his back to the window, and was addressing some associate in the street below.

"If I could once get a grasp of your collar, you would find it quite easy."

Those were the next words spoken, in the same clear curt accents that had struck upon her senses so forcibly before.

And now, like some startled fawn, Bertha, with her hands still upon the pistols, inclined her head in the direction of the casement from whence it seemed to her the new danger was approaching.

It was all danger to her apprehension—all attack, all hostility.

The fancy recognised no assistance but that which should be heralded by the voice and appearance of her father.

Who else in all the world was to help or aid her?

Had he not often told her they stood alone in the wide world, and that when she rested upon his breast, with his arms about her, there was no other breast and there were no other arms amid all the teeming humanity of nature where she could look for succour or support?

"Lost! lost!" she cried, "and he comes not."

"You are not so good at climbing as I. Let me leap down, and you can easily scramble up on my shoulders. I will then follow you."

That was the voice again from the balcony—the same voice as before.

It was becoming familiar, and did not bring such terror in its tones as at first.

Scrape! scrape! scrape!

That was at the door.

Then there was a sharp rap on its outer panel.

"Open, girl! Open! Open the door! There is no

p. 34

harm intended you. I've come to save you. Put aside your pistols and open the door."

Those were words which seemed to be projected through the keyhole of the massive lock.

But Bertha did not answer.

With the startled look of fixed attention, she still inclined her head towards the window.

But still she heard whatever passed at or about the door of the apartment, and, dividing her attention between the balcony and the original source of danger, she heard words impatiently spoken, which, although she did not understand the precise signification of them, sufficiently contradicted the assertion that those men came with any friendly intentions.

"Hang her! Try the pick again, Josey."

The scraping at the lock of the door recommenced.

And now all was still without the window, save a rustling sound of a strange fluttering character, as though some winged messengers from the dim air about the ancient house were there congregating either to pity or protect.

Was she indeed surrounded by those enemies her father had frequently warned her of?

Was it possible that her young life was to become the sacrifice to hatreds or jealousies his existence had engendered? And was he, with all the world of love that he felt for her, to find that in so temporary an absence she was to be taken from him for ever?

Was she, too, to look upon life so briefly, and then be hurried from it by violence, and with such possible pangs that the imagination might well stand aghast at their contemplation, with none near her to raise a hand in her defence?

True, she was still armed to a certain extent.

She had still the undischarged pistol, and that was the mute representative of a human life.

But of what avail would that be to her? for were not her enemies numerous, as their conversation one with another sufficiently testified?

She might kill one, but would that save her from the rage and fury of the others?

No. The air was full of murder.

The feeling of the immortality of youth was passing from her, and her career on earth, brief, sad, and beautiful as it had been, seemed near its end.

There was much that was heroic in the mind of that young girl. She could have faced death in a noble cause—she could have become the martyr or victim of a principle or a truth—she could have placed herself vanward in front of in any danger to save another whom she loved—and as yet she loved none other than that father who was far away.

But it was terrible to kneel upon that old chair and wait for death—death without a sentiment to surround it with a halo of romance—death without the throb of joy that would have accompanied it as the sacrifice for another.

These and a hundred such thoughts, winging their way with that mental electricity that permeates the brain at such moments, filled the imagination of Bertha with countless agonies. And then there was a sharp metallic sound at the lock.

The door had yielded!

Now the time had come.

The minutes of mental agony that had swelled themselves into hours of dreadful expectation had passed away.

Here is the crisis at last.

A gleam of light.

Ferocious eyes glaring at her.

Exclamations and threats mingled in one diabolical chorus.

"Fire!"

She has not spoken the word herself, but it seems to ring in her ears like a command from something in the air above or about her.

She pulls the trigger of the second pistol.

There is a faint muffled report, a scatter of sparks, a flash of light, and one mounting ring of blue smoke.

The pistol has missed fire.

It was something in those days if one pistol out of two performed its office.

"Now seize her and finish her. There is nothing to fear. At her at once, or she'll scream!"

That was a suggestion.

Bertha did utter one cry as she shrank back to the window of the apartment.

Had she miscalculated the distance? or was the slight force with which she came against the casement sufficient so completely to shatter it? for with successive crackling crashes the old diamond-shaped panes began to fall about her.

And then she told herself she was lost indeed, for an arm was flung around her, and she felt herself lifted on to the balcony.

"Fear nothing," whispered a voice. "Fear nothing, but crouch down, to be out of the line of the shots."

Bertha mechanically obeyed the command, and then, as if there was something in the crouching attitude of which her courageous heart was ashamed, she rose up again and stood her full slender height in the balcony amid the wreck of the shattered casement.

A rapid interchange of pistol-shots and some yells and cries from about the door of the apartment brought the contest to a close.

The thieves precipitately retreated, cutting off pursuit by shooting some heavy bolts on the outer side of the massive mahogany door, and then the same voice that had cautioned Bertha to crouch down spoke to her in sad but re-assuring accents.

"Thank Heaven we have been in time to save you from a great danger."

The young girl clasped her hands, and for the first time in the midst of all that peril tears burst from her eyes.

"Thank Heaven! thank Heaven! Yes, I did wish to live for him!"

There was no light in that balcony and in the antique chamber save that which streamed through the shattered casement from the street lamp nearly opposite.

And that illumination was dim and inefficient, for the lamp, with the usual perversity of such street lights, was gradually expiring, at the hour when it was most needed.

All that Bertha could see then was one shadowy form close to her and bending low, as if with an effort to scan her features, and another, still more dim and shadowy, in the apartment itself, apparently making an effort to procure a light.

Then there came a-drift of rain and a surging gust of wind from the direction of the river.

"Be careful of the broken glass," said the shadowy form that was close to Bertha.

As he spoke he lifted her gently and tenderly from the balcony, over the fragments of the casement into the room.

"My matches are damp," said the voice of the man who was endeavouring to procure a light. "My matches are damp. I so seldom use them that they remain too long in my possession. Bah! There goes another!"

There was a flicker for a moment, and then all was darkness again.

"I can get a light," said Bertha.

"Thank you, thank you; but this one I think will do. It's not so much the fault of the matches, after all, as the rush of cold air from the broken window, for now that I shield this one it burns merrily enough."

The apartment was illuminated by the flickering flame of the match, for, although the modern lucifer, or vesta, or whatever it may be called, had then no existence as an article of current use, yet the germ of that enormous revolution in the means of procuring sudden light existed in what were called thieves' matches anterior to the date of our story.

"If one had but a candle now," said the man who had lit the match.

"Here!" exclaimed Bertha.

"Ah! now we're all right. But we must keep out that gust of night wind, and the rain too, that makes its way even to the middle of the floor here."

"I will draw these heavy curtains," said the other stranger, who had not spoken for some moments.

The curtain rings, with a rushing sound, ran along the metal pole that carried them, and then, as the small flame of the candle ascended clearly into the calmer air, those three persons, so strangely thrown together into that rich and ancient apartment, looked with curious and interested eyes at each other.

CHAPTER VIII.

A FLIGHT IN THE AIR.

They were all three strangers.

One was our recent acquaintance in the scarlet coat who had somewhat startled the thieves in their rendezvous in the underground regions of the Red Cap. The other wore the undress uniform of an officer of the Guards, and was none other than our interesting friend Captain Weed Markham.

And poor Bertha looked from one to the other with inquiring eyes, while soon the gaze of both these men was concentrated upon the wondrous beauty of the fair young face before them.

"What could have brought danger, even to the threat of death itself, about one so young, so innocent, and so—"

Captain Weed Markham felt that there was a certain impropriety at the moment in alluding to the beauty of the young girl whom he had assisted to rescue.

"I think," said the man in the faded scarlet coat and the rich cravat, "I think I can enlighten you, sir, a little on that score."

"Indeed?"

"Yes, and without questioning me as to where my information is derived from, I advise you, if you have a Treasury order about you for a large sum of money, to remove yourself and it as soon as possible out of the atmosphere of this house, and its close neighbour, the old Red Cap."

"I do not understand you," said Markham.

"Indeed? Are you not the young lady's father?"

Markham shook his head.

"Oh, tell me!" exclaimed Bertha—"either or both of you, tell me something of my father. Where is he? Why is he not here? Speak, I implore you! Speak to me of my father!"

The highwayman whistled.

"This is something I can't understand," he said. "Why, sir, when I looked from the balcony I saw you at the door of this house. I asked you if you sought the young girl who was waiting anxiously for your arrival, and, as you replied in the affirmative, I assisted you up to the casement, where I suppose we were neither of us a bit too soon to be of good service."

Bertha looked with eager eyes into the face of Markham, and her very soul seemed to hang upon his reply.

He turned his gaze from her, for he feared that, let him say what he would, the truth of the terrible tidings he must sooner or later communicate to her would show itself even in the lineaments of his countenance.

It was a great relief to Markham when the highwayman lifted up his hand in a listening attitude.

"Hush! I hear noises in the house. Tell me, my dear, are you alone here? or is there any one else in the way of servant, or otherwise, that may be stirring in the mansion?"

"Alone—quite alone," said Bertha.

"Then if you don't mind lending me the light for a few minutes, I'll go on a voyage of discovery."

"Not by yourself," said Markham.

"Oh! no, not entirely. I have two little friends here in my breast who can speak with sharp tongues when I want them."

"Nay, but from the glance I had at the half-open door a while ago there seemed at least some six or eight ruffians."

"Likely enough," replied the highwayman, "but there is not the heart of a man among the whole lot of them. Ah! so, so! the door is fast on the outer side, and they think they have caged us. Well, my good sir, we must oven take our departure the way we came, and, since you are not the father of this young damsel, perhaps it would be well that we wait yet a while for his arrival."

"He will be sure to come," said Bertha.

There was a glance, sharp as a lightning flash, from the eyes of Markham to those of the highwayman, and the latter then cast down his gaze, for he understood perfectly that the reply to those last assured words of Bertha would be such as to wring her heart.

And Bertha saw something of the glance, although she guessed not its full import.

With a rapid movement she stepped forward, resting both her hands upon Markham's arm as she looked inquiringly in his face.

"You have seen my father?"

"I have."

"And—and—"

"Hush!" again cried the highwayman. "What is this filling the air? Are my eyes at fault? Or is there a fog from the river making its way into the house?"

"What is that?" exclaimed Bertha.

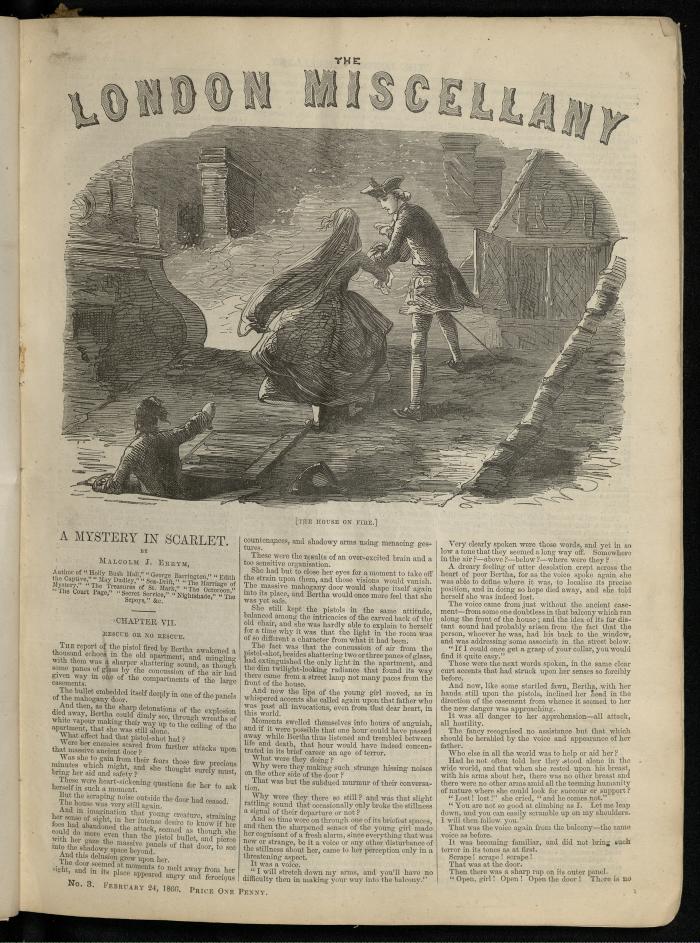

She pointed eagerly to the door of the apartment, and there, through the keyhole, and between it and the floor, where there was a narrow crevice, there came a dull red glare as though that door were the entrance to a furnace which was glowing in crimson intensity beyond.

"Fire!" exclaimed the highwayman.

Markham placed his hand upon his sword.

"Not much good in that, my friend. We must get out of here as quickly as we can, and, by Jove! it's rather awkward—that is to say, it might be if those fellows had an ounce of true courage among the lot of them."

"We shall be suffocated in this rapidly accumulating smoke."

"No fear of that. Out with the light, and draw those curtains again. The night wind and the rain will be too much for the vapour. Ah! that is a welcome breath. Look how the smoke curls off to the farther end of the room, and of all the rain that ever beat upon my face before on road or common this seems the most welcome. It's fresh and beautiful as dew from heaven."

Now that the light in the apartment was extinguished the dull red glow through the keyhole and crevices of the door became more intense and apparent.

Captain Markham was about to say something when a voice from the street arrested his attention.

"We give two men and a girl into custody for highway robbery. They made their escape into this house, and we call upon you, watchmen and officers, to effect their capture."

"What do they mean?" whispered Markham.

The highwayman smiled, and, stopping into the balcony of the mansion, he leaned carelessly over it, gazing into the street below.

"We will trouble you, gentlemen of the watch," he said, "to clear the way for us, and we will willingly surrender with all our booty."

A confused murmur of voices arose from below, and a sharp clattering sound, caused by about two turns of a watchman’s began to awaken the echoes of old Westminster.

"Brain him!" said a voice.

There was a half-smothered cry, and all was still.

"That's the Ferret's gang," said the highwayman.

"They are personating watchmen, and that was a real one who started up and began springing his rattle. He will probably never spring another in this world."

"Gentlemen, if you be gentlemen and did not really intend robbery," said a voice from below, "come down and let the watch decide."

"There is a slight difficulty," said the highwayman. "The staircase of the house is on fire, and the door of this room is fast on the outer side."

"Bring the ladder, Joseph."

"Oh! if you have a ladder," added the highwayman, "all is well, and we can descend easily. We will only

p. 35

go into the room to collect a few valuables, and will be with you in a moment."

The highwayman placed his hand upon the arm of Captain Markham, and led him just across the fragments of the casement into the room again.

Bertha followed Markham, clinging to him closely, with a feeling that he was somewhat sanctified in her eyes since he had told her he had seen her father.

"One moment," whispered the highwayman.

He crept back into the balcony in a crouching attitude.

"I tell you what it is," said a low voice from below.

"This matter must be managed in a straight forward manly manner, and we must be prepared to knock them both on the head the moment they come down from the balcony."

"And the sooner the better, too," growled another, "or we shall have the real watch upon us."

The highwayman crept back.

But now the room was so filled with dense smoke that if there had not been such a free admission of night air through the broken casement, it would have been impossible to exist in it.

The darkness, too, was as nearly complete as possible, for the thieves in the street had extinguished the neighbouring lamp, and, owing to the state of the weather, there was not oven that dim lingering twilight in the open air which, except in the presence of clouds, is always to be found at any hour in the purer atmosphere.

"What is to be done?" whispered Markham.

"We must get out of this. I feel certain the fire is spreading under the floor."

"Our situation, then, is more than critical."

"It is."

"If we attempt to make our way through the flames we shall surely perish, even if we could get yonder door open."

"Which, my good friend, we will not be so foolish as to attempt."

"To descend by the balcony, then, would be but to fall into the hands of those cutthroats below, who seem bent upon our destruction."

"True. If you and I were alone here, I should say, 'Let us leap down and have it out with them;' but with this young creature, how are we to do that?"

"How, indeed?"

"A chance blow with a bludgeon or the butt end of a pistol, or the random thrust of a rapier, might put an end to all our cares on her account."

"Then it seems, unless aid comes from some unexpected quarter, we are lost."

"Not exactly."

"What do you suggest?"

"You see the rain and wind beat full in front of the house, and those rascals below are crowding and crouching under the balcony for shelter."

"Doubtless that is so."

"Good. Then we will not descend, and yet escape."

"In what way?"

"By ascending. Now, my dear, bring your pretty face a little closer to mine, and, without speaking much louder than a young canary bird in its native woods, tell me what room there is immediately above this."

"It is my father's chamber."

"What kind of window has it?"

"A latticed one, like this, but somewhat shorter."

"But to work our way through the ceiling of this apartment," said Markham, "seems to me next to impossible."

"It is quite impossible," replied the highwayman, quietly. "But this room is as near as possible ten feet in height. I am six of those feet, and one of these chairs about two. Indeed, with the assistance of its back, heavy and massive as it is, we get more height. So, putting this and that together, I don't exactly see what is to hinder me from making my way from the outside to the upper chamber."

"Saved!" exclaimed Markham.

"We will try."

"But my father?" said Bertha—"my poor father? When he returns, who shall say to him where I am and what has happened?"

"I have a message to you from him," said Captain Markham gently. "He will not return here to-night, and he desires that you trust me and accept of my protection."

"I will."

It did not seem to occur to the innocent mind of Bertha to doubt this statement for a moment, and she only clung more confidingly to the arm of Captain Markham. The rain increased and the wind howled more furiously than before.

The highwayman carried out a massive chair to the balcony, and placed it with its back against the wall of the house.

"Now," he whispered, "wait for me a moment, and I will clear the way."

Markham was alone with Bertha.

There was a strange suffocating odour in the room, and a flickering light, so intensely blue that it was almost painful to look upon, began to flutter over а portion of the floor.

It caught the Persian carpet that partially covered the oaken flooring, and the fabric began to shrink up and writhe like a living thing.

"Now!" said the highwayman.

He had returned so quickly and suddenly that Markham started at the sound of his voice, for his thoughts had wandered away to the old gardens at Kew and the dying look of that Mystery in Scarlet as he recommended to his sacred care the fair young creature who was even now clinging confidingly to his arm.

"Now," added the highwayman, "you must make a scramble for it, my good sir, and as quietly as you can, too. By the assistance of the chair and its back, I think you can get hold of the window-sill above. You will find the casement open, and have nothing to do but to drag yourself into the room. I shall then be able to hold up this little one sufficiently high for you to be able to help her to the same place of refuge, and when once there you may leave the rest to me."

Perilous as this mode of escape was, Captain Markham saw that it was the only one that presented itself. To hesitate was to lose even all chance of that out let from the dangerous trap in which they were enveloped.

Out into the rushing rain, and buffeted by the gusty wind, he made his way, scarcely seeming, amid the intense darkness, a blacker shadow then the inky atmosphere by which he was surrounded.

It was a sharp and fearful struggle, for Captain Markham wanted some inches of the height of the highwayman; but he did succeed in dragging himself up by his hands to the sill of the upper window.

Had not the casement been open, he must have relinquished the attempt to get into that apartment in despair, for, as it was, he could only fling himself bodily forward, falling heavily on the floor.

The sound from above, however, sufficed to let the highwayman know that Captain Markham had succeeded in gaining the chamber.

"Now, my dear," he said gently to Bertha, "trust yourself with me for once, and, although I am but a lone man in the world, and have no little girl of my own to open the well-springs of my heart's affection, I will to you be as true and gentle as though I had twenty to call me by the name of father."

Another moment, and he was out in the balcony with her.

He stood upon the chair, with his hands clasped round her slender waist.

"On to my shoulder," he whispered. "Spring! It is but like a child's game at romps. There, capital! Feel for his hands! Hush! Not a word! Bravo! Gentlemen all, below there, we've made up our minds to stay and be roasted rather than come down, and in the meantime, if any of you are tired, there's a chair in the balcony."

Without another word, the highwayman sprang to the upper window, and before you could have counted five with moderate speed he stood by the side of Markham and Bertha.

"Fire! Fire! Fire!" shouted some voices from the direction of the neighbouring streets.

CHAPTER IX.

A SQUALL ON THE THAMES.

The flames kindled by the thieves in the hall of that old Westminster mansion, besides partially consuming the staircase, had spread towards the back of the house.

The boisterous wind of that night, blowing in at numerous crevices, had swayed and wafted the long tongues of flame in the direction of some outbuildings composed of much lighter materials than the house itself, and so a bright crackling flame had ascended, quite clear of the mansion, at the back, much in the same manner as if the ground floor had been a furnace, those outbuildings a chimney shaft, through which the beautiful and destructive element forced its way.

The hitherto black night-clouds assumed a roseate tinge, and the cry of "Fire!" from many voices might be heard from many parts of old Westminster.

"What are we to do now?" said Captain Markham. "The house seems in actual flames below, and we have but reached a higher point on what may be our funeral pile."

"But we will step off it on to another pile," replied the highwayman. "Come out to the landing here. By Jove! that is a pretty sight."

From the staircase landing immediately outside the door of that second-floor chamber they could look down into the old spacious hall below.

The sight was something more than pretty. It partook of the grand, the majestic, the beautiful.

Owing to the exceedingly tough tenacious character of the open woodwork which there abounded, the flames had achieved nothing of that wild rolicksome appearance which lighter materials would have given rise to, but had been forced to do their work insidiously, and were quietly curling, licking, and fluttering round the hard black balustrades and rich carving of the staircase.

The effect was at once strange and beautiful, for those balustrades, with all their carving and ornamentation, had been thoroughly burnt through, and yet preserved their shape and substance, of a glowing red heat, that sent forth sparks, now and then, of brilliant radiance, and only gradually became calcined into ash, that fell about in white filaments as the thorough decomposition of the material continued.

Bertha shuddered.

"I never saw so strange a sight," said Captain Markham.

"It is the way that old oak will burn. But one step upon that staircase would bring it all down together. Thank the fates our way is upward, not downward."

"I begin to comprehend you," said Markham.

"Of course you do."

"You mean to get from the roof of this house on to some adjoining building?"

"Precisely; and, thanks to overhearing some of the counsels of those rascals who have given us some trouble to-night, I know that there must be a tolerably easy route from the roof of this house to that of the Red Cap."

Strange pungent vapoury fumes ascended from the fire below.

It was difficult to breathe, even upon the upper staircases, although they were entirely untouched by flame.

There was no occasion for any light to guide the fugitives on their way, for the bright red radiance in the lower part of the house sent up a glow like a tropical sunset.

A hot atmosphere, likewise, as though the door of a furnace were opened, came rolling upward.

"This won't do," said the highwayman. "And the sooner we feel the night rain upon our faces the better for us all."

Then there was a loud crash.

A hundred million sparks flew upward.

The red-hot oaken staircase had fallen.

One glance into the chaos of brilliant embers below was sufficient, and the highwayman dragged both Bertha and Captain Markham into one of the upper rooms of the house, the door of which he instantly closed.

"Out and away!" he cried. "And the sooner the better. I felt the cold air rushing down from here, and I've no doubt it helped to beat back the flames from ascending the stairs.

The room was a miserable attic, for in houses of great pretensions at that period, and indeed frequently in our own, the upper floors were completely sacrificed to the reception-rooms.

A slant roof, a latticed window, and a square opening in the only flat portion of the ceiling, right out into the open air, through a dreary sort of loft between the rafters, constituted all that was remarkable in this attic region.

"This is the way the Ferret brought his companions," remarked the highwayman, "and we have but to follow the track from the old Red Cap."

There was not a tenth part of the difficulty in getting through this trap-door that there had been in ascending from the first to the second floor of the house.

The wind was boisterous, however, and the rain fell in heavy splashes upon the little party.

A brief scramble along a leaden gutter, and then past a stack of chimneys, brought them on to the roof of the Red Cap.

"Exactly as I expected," said the highwayman.

"Here is an open trap to one of the Red Cap's attics, and in we go."

"We are safe, then?" said Markham.

"I should say yes, and you have but to decide when you reach the door of the Red Cap whither you will go, and I will conduct you in safety, which way you choose—east, west, north, or south."

"I scarcely know," replied Markham, hesitatingly, "but it seems to me, from the brief observation I took of this house and its neighbour, that their entrances lie sufficiently close together to make it scarcely safe for me to emerge in the way you mention with my fair young charge here."

"True; I had forgotten," said the highwayman.

"We can come down to the water-gate. You have no idea of the extent of the Red Cap. It goes at the back right down to the Thames, and there, if you have a fancy for a little river navigation, you can take a boat, in the most literal sense of the term, for on such a night as this there will be no one to prevent you."

"I should much rather approve of that plan," replied Markham. "Do you not think that will be the safest?"

He addressed these words to Bertha, inclining his head down to her as he spoke.

"I know not—I cannot say; but, since my father has trusted to you, I trust to you."

The highwayman, without another word, led the way down some dilapidated old back staircases of the Red Cap, and, threading a passage through a wilderness of outbuildings, with all of which he seemed perfectly familiar, he at length emerged at the top of a slippery flight of wooden steps, at the foot of which the river, in as great a commotion as such confined and inland water was capable of, was lashing and foaming.

"Here we are; and now I may say good night and Heaven speed you. You may, or you may not, have the purchase of a principality about you; but if you have, I would recommend that you take better care of yourself than, I may say, I hope without offence, you would have done by yourself to-night."

The highwayman did not wait for a reply, but, turning hastily, disappeared in the gloom of the outbuildings.

p. 36

"Stay! Stay!" cried Markham. "One word with you before we part."

"Stay yet a moment!" said Bertha, and her softer and more musical accents reached the ears of the highwayman.

He was back to them in a moment.

"Can I do anything; further to aid or help you?"

"No," replied Markham, "but we ought not to part thus. I owe to you my life, and you have saved this much more precious one. I dare not, in the ordinary language of the world, say that I thank you, for those words would sound but poor and frivolous."

"Say nothing—say nothing."

"But I must say something," interposed Bertha.

"You have saved another life to-night than those which have hung upon your devoted courage for the last half-hour. My father, sir, lives but for me, as I for him, and had I perished so wretchedly as it was the intention I should on this night of terror, he too must needs have died, for life must have gone from him, along with the only hope and joy of his existence."

"Say no more—say no more. Do you think I could possibly let those rascals have their way? There are several boats down there in the stream, and the tide is running up. You may land anywhere you will, and I think the fierce wind is abating, and the clouds look lighter; so now again good night."

The careless manner of the highwayman evidently hid deeper emotions, and he doubtless wished by those ordinary words to overpower the earnest thanks that were rendered to him.

"I would fain not part with you," said Markham, "without knowing who and what you are, as well as where I can meet with you again."

The highwayman laughed.

"It's a wise thing," he said, "to ask three questions in a breath, since one or other of them may be answered."

"But you will answer all?"

"Nay—only the last. Who and what I am matters not, but if you want to meet with me again, stand on any Thursday night you like beneath an old Norway pine tree that is close to the margin of a brook some where about the middle of Ealing Common, and fire two pistols in the air, with an interval of about half a minute between each. If I am alive, you will see me in about five or ten minutes, and if you see me not, give me as brief a prayer as you may, for I shall have gone to my account; and so now, once more, good night."

The dull red glare of the conflagration now tinted the mimic waves of the Thames with crimson and gold.

There was the subdued roar as of a multitude of people, the voices of the flames and of their human spectators mingling to produce the sound. Captain Markham, with his arm round the slender waist of Bertha, more than half carried her down the slippery wooden steps to the river's brink.

"To my father," she said in low whispered accents. "I will tell you of him."

"I will tell you of him."

"But I must— must see him. I do not know when we have been so long apart."

"Be patient, dear girl, for yet a little while, and rest assured that, as your father's friend, and one to whom your care was committed by fervent words from his own lips, I will protect you with my life."

A brighter glow shot up into the night sky as Captain Markham, finding a wherry in which the oars had been fortunately left, pushed off from the old slippery steps of the Red Cap, and commenced rowing with the tide up the stream, while the glow of the fire imparted to the fair face of Bertha an expression something more than mortal.

(To be continued in our next.)