A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by

Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER XVI.

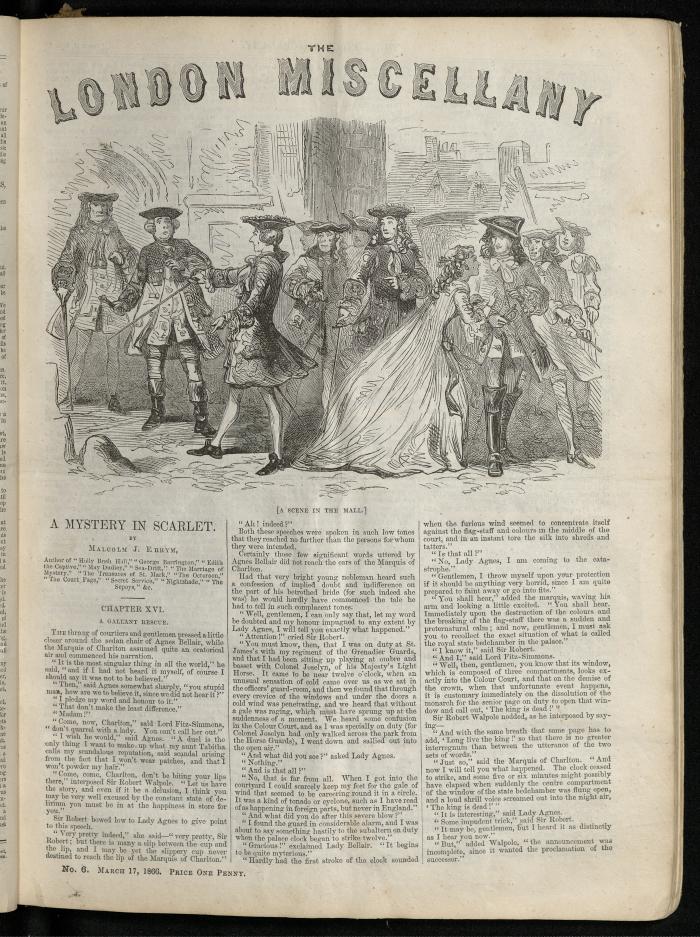

A GALLANT RESCUE.

The throng of courtiers and gentlemen pressed a little closer around the sedan chair of Agnes Bellair, while the Marquis of Charlton assumed quite an oratorical air and commenced his narration.

"It is the most singular thing in all the world," he said, "and if I had not heard it myself, of course I should say it was not to be believed."

"Then," said Agnes somewhat sharply, "you stupid man, how are we to believe it, since we did not hear it?”

"I pledge my word and honour to it."

"That don't make the least difference."

"Madam!"

"Come, now, Charlton," said Lord Fitz-Simmons, "don't quarrel with a lady. You can't call her out."

"I wish he would," said Agnes. "A duel is the only thing I want to make up what my aunt Tabitha calls my scandalous reputation, said scandal arising from the fact that I won’t hear patches, and that I won’t powder my hair.”

"Come, come, Charlton, don't be biting your lips there," interposed Sir Robert Walpole. "Let us have the story, and even if it be a delusion, I think you may be very well excused by the constant state of delirium you must be in at the happiness in store for you."

Sir Robert bowed low to Lady Agnes to give point to this speech.

"Very pretty indeed," she said—" very pretty, Sir Robert; but there is many a slip between the cup and the lip, and I may be yet the slippery cup never destined to reach the lip of the Marquis of Charlton."

"Ah! indeed?"

Both these speeches were spoken in such low tones that they reached no further than the persons for whom they were intended.

Certainly those few significant words uttered by Agnes Bellair did not reach the ears of the Marquis of Charlton.

Had that very bright young nobleman heard such a confession of implied doubt and indifference on the part of his betrothed bride (for such indeed she was) he would hardly have commenced the tale he had to tell in such complacent tones.

"Well, gentlemen, I can only say that, let my word be doubted and my honour impugned to any extent by Lady Agnes, I will tell you exactly what happened."

"Attention!" cried Sir Robert. "You must know, then, that I was on duty at St. James's with my regiment of the Grenadier Guards, and that I had been sitting up playing at ombre and basset with Colonel Joselyn, of his Majesty's Light Horse. It came to be near twelve o'clock, when an unusual sensation of cold came over us as we sat in the officers' guard-room, and then we found that through every crevice of the windows and under the doors a cold wind was penetrating, and we heard that without a gale was raging, which must have sprung up at the suddenness of a moment. We heard some confusion in the Colour Court, and as I was specially on duty (for Colonel Joselyn had only walked across the park from the Horse Guards), I went down and sallied out into the open air."

"And what did you sее?" asked Lady Agnes.

"Nothing."

"And is that all?"

"No, that is far from all. When I got into the courtyard I could scarcely keep my feet for the gale of wind that seemed to be careering round it in a circle. It was a kind of to[r]nado or cyclone, such as I have read of as happening in foreign parts, but never in England."

"And what did you do after this severe blow?"

"I found the guard in considerable alarm, and I was about to say something hastily to the subaltern on duty when the palace clock begun to strike twelve."

"Gracious!" exclaimed Lady Bellair. "It begins to be quite mysterious."

"Hardly had the first stroke of the clock sounded when the furious wind seemed to concentrate itself against the flag-staff and colours in the middle of the court, and in an instant tore the silk into shreds and tatters."

"Is that all?"

"No, Lady Agnes, I am coming to the catastrophe."

"Gentlemen, I throw myself upon your protection if it should be anything very horrid, since I am quite prepared to faint away or go into fits."

"You shall hear," added the marquis, waving his arm and looking a little excited.

"You shall hear. Immediately upon the destruction of the colours and the breaking of the flag-staff there was a sudden and preternatural calm; and now, gentlemen, I must ask you to recollect the exact situation of what is called the royal state bedchamber in the palace."

"I know it," said Sir Robert. "And I," said Lord Fitz-Simmons.

"Well, then, gentlemen, you know that its window, which is composed of three compartments, looks exactly into the Colour Court, and that on the demise of the crown, when that unfortunate event happens, it is customary immediately on the dissolution of the monarch for the senior page on duty to open that window and call out, 'The king is dead!'"

Sir Robert Walpole nodded, as he interposed by saying—

"And with the same breath that same page has to add, 'Long live the king!' so that there is no greater interregnum than between the utterance of the two sets of words."

"Just so," said the Marquis of Charlton. "And now I will tell you what happened. The clock ceased to strike, and some five or six minutes might possibly have elapsed when suddenly the centre compartment of the window of the state bedchamber was flung open, and a loud shrill voice screamed out into the night air,

'The king is dead!'"

"It is interesting," said Lady Agnes.

"Some impudent trick," said Sir Robert.

"It may be, gentlemen, but I heard it as distinctly as I hear you now."

"But," added Walpole, "the announcement was incomplete, since it wanted the proclamation of the successor."

p. 82

"That came, Sir Robert, after a moment's pause, and as quickly as it seemed to be possible for the person who had made the first announcement to gather breath to make the second."

"Ah! You don't say so?"

"I heard it, gentlemen, I heard it, and it was comprised in these words, 'Long live the queen!'"

"The queen?" exclaimed every one.

"What queen?" asked Agnes.

Sir Robert Walpole laughed.

"There is just the difficulty," he said, "and it is evident that Charlton's ghost knew nothing of the order of succession. On the demise of his present Majesty—whom, Heaven preserve—his Royal Highness Prince Frederick succeeds, and should the malignant Fates deprive us of that gracious prince, his infant son George becomes King of England. So there is no queen to cry 'Long live' to, and the ghost must have been in a state of mental confusion."

"I don't know," said the marquis. "I only relate to you, gentlemen, what I heard, and if I were to live for a thousand years—"

"Which Heaven forbid!" cried Agnes, "for you would look dreadfully old."

"I repeat, gentlemen, that were I to live for a thousand years, nothing would convince me that I did not clearly and distinctly hear those words."

The little throng round the chair of Agnes Bellair looked at each other with incredulity and surprise, and it was something of a relief when voices were heard crying—

"Make way, gentlemen! Make way, gentlemen! Way, if you please, gentlemen! Way for her Majesty the queen!"

Leading a small poodle by a silken cord, the queen of George the Second slowly walked up the Mall, preceded at a small distance by a gentleman usher of the palace, and followed by some half dozen ladies of the court.

Every hat was removed, and the gentlemen bowed low, ranking themselves up on each side of the Mall among the trees while the royal party passed onward.

The queen consort looked placid and white, as, with a mechanical kind of smile, she slightly bowed to the right and to the left.

It was etiquette for ladies on such an occasion to leave their sedan chairs and execute one of the elaborate curtseys of the period.

The queen's eyes fell upon Lady Agnes Bellair, as, in the execution of her curtsey, she seemed to be slowly sinking beneath the gravel of the Mall, leaving her celebrated blue sac in rolled-up folds on its surface.

Agnes was a fayourite of the queen, and then occupied the position of "reading lady," as it was called, any favourite maid of honour being promoted to that condition by the queen, and the duty consisting of attending her Majesty in her private cabinet, theoretically to read, but practically to gossip.

So the queen gave a gracious smile to Agnes and passed on. The gentlemen put on their hats again, and the throng of fashionables closed up in rear of the royal procession, if it may be called such, as the sea closes up in the wake of a ship.

The Marquis of Charlton offered his hand to Lady Agnes to conduct her back to her chair.

He offered it with one of those elaborate bows that made that age a stately and dignified one, and which we still see perpetuated in some of the dances which have survived the period of their first fashion.

Lady Agnes stepped into her sedan chair, and then she uttered a slight cry, more of surprise than fear, as, glancing towards its opposite window, she encountered the dark earnest eyes of a young man gazing upon her.

"Hush! Agnes."

"Oh! Frank—it is you, dear Frank!"

"Hush! Where is my father?"

"Here—here. He was here this moment. I do not see him now, but he was close at hand. Oh! Frank! Frank!"

"Chut! Chut! Don't look at me in that way. Why do you tremble so?"

"I tremble to see you here, Frank. You are in danger. Your life—your very life, brother. Oh! I have heard such things!—such things!"

"Never mind, Agnes. I will take care of myself. But I must see my father. He has discarded me—driven me from his doors—made me the outcast and adventurer I am. But to-day I have made up my mind to see him."

"Oh! no, Frank. He is so bitter—so bitter! I have heard such things!—such things!"

"What things, Aggy?"

"Don't!—oh! don't! don't!" She had pulled down the silken blind on the other side of the sedan, almost in the face of the Marquis of Charlton, and now, clasping her hands together despairingly, she burst into tears.

"Why, what is the matter, Aggy?"

"Don't, Frank, don't! Don't call me Aggy. It puts me in mind of long ago when we were little children. Don't, Frank, don't!"

"Chut! Chut! What nonsense! Don't cry for me. I can and will take good care of myself, and the worst that has ever happened to me, dear Aggy—or Agnes, if you like it—is that one tear on my account should dim your dear eyes."

"Fly! Frank, fly! You do not know what I have heard and what they have said of you."

"Tell me, then."

"They say that—that—"

"Well?"

"That you—that you—"

"Come, come, out with it."

"That you are a—a highwayman."

"Indeed?"

"But you are not, Frank—you are not. You are a gentleman."

“A gentleman highwayman.”

"No, Frank, no! I will not believe it. I did not believe it; and when Lord Bute said it I offered to fight—no, I didn't offer to fight, but I felt as if I should like to fight everybody; and then—then, he said it."

"My father?"

"Yes."

"Well, and what then?"

"He—he said that his duty to society, or something of that sort —something cold, and curt, and cruel, and wicked—for our duty, you know, Frank, is to those whom we love and who love us—he said his duty to society would be, if he saw you or knew where you could be found, to hand you over to justice."

"So! so!"

"I hate justice!"

"Come, come, Agnes, have no fears. My horse is waiting for me beneath one of the trees close to Spring Gardens, and amicably consorting, no doubt, with the cows, who have a prescriptive right to a standing in the park; and I must see my father."

"But why, Frank? Why, when I tell you of the danger and of all the cruel things that are said?"

"Why, look here, Agnes. This is our father's birthday."

"Yes, I know."

"Well, I want to wish him many happy returns."

"Oh! Frank, how can you be so reckless? This is bravado, Frank, not courage."

"Perhaps. But here he comes."

"Fly! Fly!"

"No. I am a Bellair, and I come of an obstinate race."

Tall and handsome, wearing his hair in flowing ringlets right down to his shoulders, and cultivating a small short military moustache, Francis Bellair lounged carelessly round the sedan and its bearers.

He wore horseman's boots, the silver spurs on which jangled and jingled as he stepped.

His coat was of a light drab colour and buttoned to the chin, although the ends of the lace cravat were drawn out and thrust between two of the buttons carelessly.

The reader has seen this lithe and handsome figure already, has before met the sparkle of those bright searching eyes, and heard the somewhat mocking, yet at times tender, tones of that voice.

In the thieves' haunt at the Red Cap.

On the balcony of that house of mystery at Westminster, where Bertha for a time seemed to be abandoned by even Hope.

And at the river side, where Captain Markham, with his fair young charge, embarked amid the storm and turmoil of the seething water, those eyes watched the progress of the boat until it disappeared amid the spray and the night mists.

He was pale, for peril was about him, but he stood like some gallant sentinel on duty, who will not leave his post, although destruction hover about him.

CHAPTER XVII.

THE MAID OF HONOUR.

General Sir Thomas Bellair had a smile upon his lips, and had just lifted his hat to the Duchess of Kingston, when his eyes fell upon his son.

The general seemed transfixed and turned to stone, for he still held his hat a few inches above his head, and his attitude had all the rigidity of a statue.

Clank, clank, clank.

It took three strides of his son—the silver spurs rattling as he went—for him to roach within three feet of his father.

"Sir," said Frank, "this is your birthday. I have, with some little trouble, sought you out to wish you many happy returns of the day."

Frank then raised his hat and bowed.

"Villain!" cried the general.

"Disgrace to my name! Torture to my thoughts! Criminal!"

"Hard words, father; but I say no more.

Last year I wished you happiness and many returns of this day, and this year I have now done likewise.

Next, if I live and you live, I will do so again."

"Guard! No. Police! Police!"

There was a rush of many persons to the spot, but no one seemed inclined to lay hands in an amateur capacity upon the powerful-looking young man at whom General Bellair pointed in trembling passion.

"Police? I say! Is there no officer here to apprehend this criminal?"

"No!" cried Agnes, as she sprang from her chair and flung her arms round her brother.

"No, there is no officer who will apprehend the son upon the demand of the father, and there is no gentleman will play the amateur constable and strive to take from me my brother!"

"Agnes, you are mad!" cried the general.

"Nearly, father, nearly. But you shall not harm Frank."

"Let me go, dear Aggy, let me go. I am safe enough."

"No, no, not yet. You spoke of your home."

"Where is it?"

"Down yonder, not a hundred paces."

"I will take you. Gentlemen, gentlemen, who is there who will protect me down the Mall? Who has a sword to draw for Agnes Bellair?"

Twenty swords seemed to leap from their scabbards at these words.

"Come, come, gentlemen," said a quiet voice, "this won't do—this won't do."

A short thick stalwart man, in topboots and a soiled stained red coat, pushed forward, bearing in his hand a small gilt staff with a royal crown at the top of it.

"This won't do, gentlemen. The law is the law, and if Sir Thomas Bellair gives any one in charge, I take him."

"Gentlemen," cried Agnes, "this is my brother, and I am Agnes Bellair. It is my wish to walk with, him down the Mall."

The officer was hustled aside in an instant, and an entrenchment of drawn swords surrounded Agnes and Frank.

"This is petty treason!" cried the general, foaming with rage.

"I don't know that it is not something worse. Here are swords drawn and the law resisted within the precincts of the palace. The consequences be on your own heads, gentlemen. It is brute force— brute force."

"But, my dear general," said a young lady, with a profusion of powdered curls, and who was that same Duchess of Kingston to whom Sir Thomas had been bowing—"my dear general, they seem to consider that you are the brute."

"Madam!"

"Exactly, general, for as that charming young man only came to wish you many happy returns of your birthday, you might have said 'Thank you,' and there's an end."

"Madam, duchess, you know not what you speak of. That charming young man of whom you speak is my son."

"Exactly, general, and it is remarkable that he does not bear the slightest resemblance to his father."

The police officer stood aghast at the turn affairs had taken, for he recognised among the defenders of Agnes and her brother some half dozen ministers of state, two or three of whom were actual members of the Cabinet.

The fair Agnes, therefore, went down the Mall in triumph, still encircling her brother with her arms. It was a pretty and a picturesque sight to see that gentle and most feminine-looking girl, tall enough as she was among women, but slender and petite by the side of the stalwart young man to whom she clung.

Who would attempt to interfere with her now?

Who, even if he could have done so efficiently, would have been bold enough to lay up the after-reflection in his mind that he had spoilt that act of courage and heroism?

On the contrary, there was no one there present who would not have risked something—something of liberty —something perhaps of life—to help her on her way.

And Sir Thomas Bellair, even in the midst of all his passion, of all his rage, and all his pain (for he had that indescribable pain of believing that he had a thankless child in his son Frank), shrank aside and avoided observation.

He felt that if ever man were on an unpopular side of what had become a public question, he was that man on that occasion in the old park of St. James's.

The distance was short.

The crowd cheered.

There was a waving of hats and a glitter of sword blades.

And then Agnes scarcely knew how it was accomplished, but she found herself with her brother close to the little wooden huts by Spring Gardens where since the days of the first Charles a couple of cows had had the privilege of supplying milk to his Majesty's lieges.

Then the young man bent his head and kissed his sister on the brow and on each cheek.

"Farewell, Aggy. When I am forgotten the whole world will remember you."

Another moment and he had mounted a dark chestnut horse that stood quietly close to the cows, and which, with the sagacity of the creature, when that sagacity is developed by human kindness, attention, and association, had sidled up to him with the playful action of a dog.

Agnes could not speak.

There were tears in her eyes.

And now that the excitement was over—now that her brother was free (for she felt that he was free when once he was fairly mounted)—she trembled excessively.

Frank Bellair cast one glance over the sea of heads in the Mall, and, raising his hat slightly, he said, with something of scorn in his tone—

p. 83

"Ladies and gentlemen, I have the honour of bidding you all good day."

He touched his horse slightly with his open hand upon the flank.

There was a curvet and a bound, and off they went.

"Lady Agnes Bellair's chair!" cried a young man in a purple stile coat richly embroidered, as he offered her his arm.

"Thank you, Lord Orton, thank you. I require some support, although Heaven knows I have had more this day than I can ever find words to thank you all for."

It was quite an ovation, the taking possession of her chair on the part of Agnes Bellair.

And if she were beautiful before, and full of charms in form and feature, the flush the excitement had brought upon her face invested her with a brilliant beauty that was something more than mortal.

The Marquis of Charlton stood, with his sword still drawn in his hand, close to the chair.

The young Lord Fitz-Simmons assumed a post on the other side of it.

But the consequences of this triumph of Agnes Bellair in the great Mall seemed in some measure yet to come.

A young subaltern of the Guard approached the Marquis of Charlton, and, saluting him ceremoniously, said in low tones—

"I am very sorry, marquis, hut by order of General Bellair I am desired to inform you that you must consider yourself under arrest."

"Indeed?"

"Yes, marquis; and he requests that you will hand me your sword, and retire at once to close quarters in St. James's."

For a few seconds the marquis seemed disposed to resist this order, but he knew that General Bellair was in full command of the London district and all its forces.

Prudence, therefore, got the better of the momentary irritation.

"Take my sword, Mr. Ogilvie," he said. "I shall obey the general's order, of course, but shall insist upon a court-martial."

The subaltern bowed.

"What is this?" asked Agnes. "Is it on my account?"

"Faith!" replied the Marquis of Charlton, "I can scarcely say; but here comes one of the queen's pages with so serious and lengthy a face and with his eyes so bent upon this sedan chair that I am afraid he brings some disagreeable message."

"I have no sword to give up," replied Agnes, with something of her usual vivacity, "but perhaps I, too, shall be put under arrest."

"That would be something new. But here he comes. It is Mr. Curtis, I think, the page of the presence."

The page bowed.

"I am sorry, Lady Agnes Bellair, to say that her Majesty, with some displeasure in her tone, requests that you will be so good as to return at once to your own apartment in the palace, and there wait her Majesty's pleasure."

"Certainly, Mr. Curtis, certainly. I am your prisoner."

"Oh! no. Lady Agnes, oh! no. I merely deliver a message. It is I, Lady Agnes, who have been your prisoner since I know that I possessed a heart capable of being enchained in the—the—"

"Now, my dear Curtis," cried young Lord Orton, "never commence a complicated compliment until you are quite certain you have the fag end of it well in your mind."

"My Lord!"

"Oh! we won't quarrel, Curtis, we won't quarrel."

"To the palace," said Agnes, "to the palace at once. I obey her Majesty's commands with alacrity and pleasure. I believe her Majesty has a brother likewise whom she would gladly have helped to a horse and an escape on more than one occasion."

Perhaps this was the hardest and most sarcastic speech that had ever fallen from the lips of Agnes Bellair, for it was tolerably well known that the queen had a brother whose private character—to speak delicately—would not bear the strictest investigation.

CHAPTER XVIII.

SOMETHING IN THE DARKNESS.

The footsteps of his Majesty George the Second, and of Norris, his valet, died away amid the old corridors and palatial apartments of Whitehall.

One waxlight still burnt in its silver candlestick on the chimneypiece of that room in which so strange a scene had been enacted.

The wood fire had crumbled and burnt down to a few white and crimson ashes on the hearth.

And Captain Markham and Bertha were alone again.

It was a strange action—strange, unexpected, and little in accordance with her character—for Bertha suddenly tilting her arms round the neck of Captain Markham, and to hang thus almost suspended on his breast.

But she did sо, and the heart of the young officer beat rapidly, and tears rushed to his eyes, for the affectionate action touched him to the soul.

"My father is dead," said Bertha, "and he has left me to you."

Was it a question?

Was it an assertion?

It was something of both. And the silence of Captain Markham was its answer.

Then she raised her head for a moment and looked him in the face, and she saw there the traces of emotion.

His lips moved slightly, as though he were about to speak.

"Not now," she said. "Not now. When I am stronger—when I am better—when I have prayed—but not now—not now."

And so Captain Markham understood that he was to tell her nothing then, but that she know her father was no more, and that he (Markham) was her sole friend upon earth.

He folded his arms gently about her.

"With my life," he said, "always with such power as my life may give me, will I keep up the promise that I have made, and be to you both friend and father, Bertha. With my life—with my life!"

She seemed wishful to speak, and she patted his breast with her hand.

Words would not come, but better than words were sent to her relief, and the gush of tears, the passionate flood of weeping, lasted for many minutes, only subsiding in fitful gusts, like the hush and pauses of storm.

Then, pale, but silent, whiter than even paleness can express, she held Markham's arm in both her own, as she had done more than once before (it was an action probably she was accustomed to with her father), and she looked up in his face confidingly, and what would have been called calmly by any one not gifted with that delicate perception to see beneath the surface of suppressed feeling.

"All this persecution— all this trouble" (she passed her hand across his brow as she used these words)—"all this, and this—"

There was a rent in his scarlet uniform, which she indicated.

There was blood from a severe scratch on the back of one of his hands.

That she touched lightly.

"All this is for my sake and on my account."

He smiled faintly, but there was no mistaking that the smile was a grateful and a pleasant one.

"It is all nothing, Bertha, if I save you."

"Yes, but—but—"

"What would you say?"

"There are others, perhaps, as well аs I, who claim your care, your help, your courage, and—"

"And what, Bertha?"

For a moment or two the young girl's eyes wandered from his face, and the paleness gave place to a slight flush.

Then, as if ashamed of the artificiality of this emotion, she looked him clearly in the еуеs again, and added—

"Your love."

Markham shook his head.

"No, Bertha, there is not a more solitary man in all the world than I. No family, no kindred, I am in the world like some ancient Paladin, who goes forth with a heart and a sword, and leaves the rest to fate. I have a yearning for affection. It is a something in my nature which, like the air I breathe, is at once vital and necessary, and that affection, Bertha, you shall have without stint or measure. You have it now—for do we not seem as though we had known each other for years and years? It is not time itself, but the events that are crowded into any given space, that make up the measure of our existence, and so, Bertha dear, we have known each other long."

"So long!" sighed the young girl.

"Affection!"

She looked thoughtfully to the floor. Did that word "Affection" please her as well as "Love" would have done?

Perhaps not, but Bertha's heart was too heavy to draw subtle distinctions, and the future to her young imagination was like some mist, through which appeared nothing but disjointed and incongruous images.

"You are cold," suggested Markham, for he felt her shudder as she clung to him.

"Yes, Markham, I am cold."

"Wait a moment, and I will wrap you up close to these expiring embers of fire; and yet I do not see why they need expire. Wo can renew them. Here is fuel sufficient."

Markham placed Bertha tenderly on one of the old velvet ottomans before the hearth, and then breaking to pieces one of the smaller gilt chairs, he piled the pieces on the still smouldering embers that sent forth a faint glow from the hearth.

A few seconds more and the operation would have been too late, but, as it was, after some crackling and a great liberation of blue smoke the pieces of the chair sprang into flame, and a pleasant feeling of warmth began to irradiate the apartment.

"You shall sleep here, Bertha, and I will keep watch the while. By the earliest morning light I will sally forth to procure you some provisions, for we shall both need them. I may perhaps succeed were I to try even now, although the night is far advanced."

"No, no. I am not hungry, for, although we have known each other so long, as you say, the time is but short when counted by hours."

"Then sleep, dear, and I will keep watch."

"But you, too. You want rest."

"You forget I am a soldier, and it is my duty and profession to play the sentinel. Nevertheless, I will take what rest I want some few hours hence, for then I shall better see that all danger has passed away; and so good night, Bertha. I will keep my watch and ward in the adjoining room; but first I must barricade this against all intruders."

Bertha watched him wherever he went, as he carefully examined the panelling of the apartment, to see if there were any other doors than that which led into the adjoining room.

There was one immediately opposite the fireplace, but it seemed very securely fastened, and, although some of the gilt ornaments of the lock remained, the handle was removed.

Against this door, however, Markham wheeled a rather heavy couch, so that at all events it could not be opened without sufficient noise to create an alarm.

His next care was in regard to the secret panel through which the conspirators had made their hasty exit.

That was a tall, narrow, and very grim-looking opening in the wall.

Captain Markham bent his head to listen, for he thought he heard some strange sounds ascending from the gloomy-looking depth.

A few minutes' attentive listening, however, convinced him that those sounds only arose from the sighing and moaning of the wind through a space really not much larger than a chimney.

There was no difficulty in closing the panel, and as he did so Markham was careful to observe its mode of fastening, and the spring which required to be pressed in order to open it readily.

When closed its secrecy was perfect, for the whole panel represented one of a series of tall looking-glasses that were between the windows of the room. Captain Markham, however, did not feel quite satisfied with the merely closed looking-glass panel, but he placed against it several cumbrous pieces of furniture, which he moved with difficulty.

Then, he was more content, and he broke up another gilt chair, with which he fed the fire.

Bertha was still awake, and indeed all these movements of Captain Markham necessarily kept her so.

But she was much exhausted, and the fragile young life seemed now almost half extinguished by the many excitements and fatigues that had beset it.

She had watched him and she had watched the fire until, although she did not actually sleep, the past and the present had become confused and confounded in her mind.

"Good night," again he said gently.

She raised both her arms and drew his head towards her.

"Good night, good night."

And Markham felt himself sanctified by the kiss that she left upon his cheek, and he was there and then ready to do battle with all the world for her, with the faith that he must inevitably conquer.

There was plenty of firelight in the room to сhase away any gloomy shadows that might linger about it, so Markham took the candle from the chimneypiece, and lightly as foot could fall he passed out into the adjoining chamber.

How profoundly still the night was! The tempest had completely passed away, and was succeeded by one of those dead calms which equalise and average the operations of Nature.

Well Markham knew that for the last two years the whole of the extensive building known as Whitehall proper had been abandoned, and in fact that its removal was intended.

It was associated with too many disagreeable reminiscences to English royalty for it to become a popular residence.

Moreover, a great portion of its river front was falling to decay, owing to some original fault in its foundation.

Captain Markham had, therefore, every reason to believe that himself and Bertha were the only human beings at present beneath the roof of the huge straggling pile.

It was not a feeling of loneliness that oppressed him.

It was rather one of curiosity, combined with one of interest, and as he placed the candle, which shed about it so faint a light, producing that effect which has been so well described аs "visible darkness," in the more distant portions of the room, upon one of the richly inlaid tables, an intense desire came over him to explore some parts of the building.

He did not contemplate for a moment removing himself far from Bertha, but he looked upon the room in which she now slept as thoroughly protected.

It was not at all probable that more than one secret means of ingress to that room existed, and he felt that that one was well barricaded.

Hence he was partially at liberty to consider himself still a sentinel on duty over that chamber, although he might wander a little from his immediate post in the next apartment.

p. 84

And now Captain Markham, if he had had his choice, would rather have heard something of the elements without.

A scatter of rain, a puff of wind—anything that would have connected him with the physical world—would have been grateful amid the intense stillness which surrounded him.

But before he commenced his explorations he determined to think a little—to try and arrange his thoughts for the morrow—and to ask himself if he really had sufficient reason to believe the dangers of his position had passed away.

He sat down opposite the candle, and, with some thing of a feeling as though he and Bertha must surely be the last of living humanity left upon the earth, so profound was the stillness about him, he strove to think.

"Yes," he murmured, "all must he well now, with the exception of that fearful deed at Kew, which belongs to the past, and which knows no remedy. It is not and cannot be in human nature that the king (for he, too, is human) can forget that I have saved him—saved his life—as well as his crown. He may be cold, cruel, ungrateful, but he cannot be the monster of ingratitude and villany that any contrivance now against my life or fortunes would make him. I will keep this appointment at the palace. I will be candid, open, and ingenuous. I will tell him the Secret of that Mystery in Scarlet which has been confided to me, and I will only ask of him, as I asked of him here, to forget me. My life then will not be so barren and so bleak and weary, for I shall have this gentle and confiding girl resting over on my heart and best affections for support and succour, and she will learn to love me as some dear sister—to love me ever and ever."

He was silent.

What was it?

Why does he strain his eyes into the darkness?

Some light sound!

Hush! There it is again!

He holds up his hand; it is to shield the immediate glare—slight though it is—of the candle flame from his eyes.

Then he sees better into the far-off gloom of the costly chamber, and the cold drops stand upon his brow, and his heart for a moment seems to cease its pulsations. There is a something—a something!

What is it?

(To be continued in our next.)